Fluorescent lamp

One of the first to explain it was Irish scientist Sir George Stokes from the University of Cambridge in 1852, who named the phenomenon "fluorescence" after fluorite, a mineral many of whose samples glow strongly because of impurities.

The explanation relied on the nature of electricity and light phenomena as developed by the British scientists Michael Faraday in the 1840s and James Clerk Maxwell in the 1860s.

[4] Little more was done with this phenomenon until 1856 when German glassblower Heinrich Geissler created a mercury vacuum pump that evacuated a glass tube to an extent not previously possible.

Nikola Tesla made similar experiments in the 1890s, devising high-frequency powered fluorescent bulbs that gave a bright greenish light, but as with Edison's devices, no commercial success was achieved.

In 1895 Daniel McFarlan Moore demonstrated lamps 2 to 3 meters (6.6 to 9.8 ft) in length that used carbon dioxide or nitrogen to emit white or pink light, respectively.

The extended lifespan and improved efficacy of incandescent bulbs negated one of the key advantages of Moore's lamp, but GE purchased the relevant patents in 1912.

Of particular importance was the invention in 1927 of a low-voltage “metal vapor lamp” by Friedrich Meyer, Hans-Joachim Spanner, and Edmund Germer, who were employees of a German firm in Berlin.

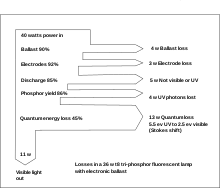

Decades of invention and development had provided the key components of fluorescent lamps: economically manufactured glass tubing, inert gases for filling the tubes, electrical ballasts, long-lasting electrodes, mercury vapor as a source of luminescence, effective means of producing a reliable electrical discharge, and fluorescent coatings that could be energized by ultraviolet light.

Stimulated by this report, and with all of the key elements available, a team led by George E. Inman built a prototype fluorescent lamp in 1934 at General Electric's Nela Park (Ohio) engineering laboratory.

[22][23] During the following year, GE and Westinghouse publicized the new lights through exhibitions at the New York World's Fair and the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco.

Electrons collide with and ionize noble gas atoms inside the bulb surrounding the filament to form a plasma by the process of impact ionization.

The lamp's electrodes are typically made of coiled tungsten and are coated with a mixture of barium, strontium and calcium oxides to improve thermionic emission.

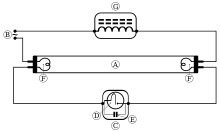

In North America, the AC voltage is insufficient to start long fluorescent lamps, so the ballast is often a step-up autotransformer with substantial leakage inductance (to limit current flow).

The choice of circuit is based on cost, AC voltage, tube length, instant versus non-instant starting, temperature ranges and parts availability.

If timed correctly relative to the phase of the supply AC, this causes the ballast to induce a voltage over the tube high enough to initiate the starting arc.

It consists of a normally open bi-metallic switch in a small sealed gas-discharge lamp containing inert gas (neon or argon).

The glow switch will cyclically warm the filaments and initiate a pulse voltage to strike the arc; the process repeats until the lamp is lit.

As the lamp warms and pressure increases, the current continues to rise and both resistance and voltage falls, until mains or line-voltage takes over and the discharge becomes an arc.

Every time the lamp is started, and during operation, a small amount of the cathode coating is sputtered off the electrodes by the impact of electrons and heavy ions within the tube.

Low-mercury designs of lamps may fail when mercury is absorbed by the glass tube, phosphor, and internal components, and is no longer available to vaporize in the fill gas.

The localized depletion of mercury vapor pressure manifests itself as pink luminescence of the base gas in the vicinity of one of the electrodes, and the operating lifetime of the lamp may be dramatically shortened.

The relative intensity of light emitted in each narrow band of wavelengths over the visible spectrum is in different proportions compared to that of an incandescent source.

Since the 1990s, higher-quality fluorescent lamps use a rare-earth tri-phosphors mixture, based on europium and terbium ions, which have emission bands more evenly distributed over the spectrum of visible light, but with peaks in the red, green and blue.

They are cooler than traditional halogen light sources, and use high-frequency ballasts to prevent video flickering and high color-rendition index lamps to approximate daylight color temperatures.

Oscillations are generated from the negative differential resistance of the arc, and the current flow through the tube can form a tuned circuit whose frequency depends on path length.

Unlike a true strobe lamp, the light level drops in appreciable time and so substantial "blurring" of the moving part would be evident.

Two effects are responsible for this: the waveform of the voltage emitted by a standard phase-control dimmer interacts badly with many ballasts, and it becomes difficult to sustain an arc in the fluorescent tube at low power levels.

They are used to provoke fluorescence (to provide dramatic effects using blacklight paint and to detect materials such as urine and certain dyes that would be invisible in visible light) as well as to attract insects to bug zappers.

Grow lamps contain phosphor blends that encourage photosynthesis, growth, or flowering in plants, algae, photosynthetic bacteria, and other light-dependent organisms.

They are sometimes used by geologists to identify certain species of minerals by the color of their fluorescence when fitted with filters that pass the short-wave UV and block visible light produced by the mercury discharge.