Role of Christianity in civilization

[9]: 309 Christianity in general affected the status of women by condemning marital infidelity, divorce, incest, polygamy, birth control, infanticide (female infants were more likely to be killed), and abortion.

[36][37] Rodney Stark writes that medieval Europe's advances in production methods, navigation, and war technology "can be traced to the unique Christian conviction that progress was a God-given obligation, entailed in the gift of reason.

From practices of personal hygiene to philosophy and ethics, the Bible has directly and indirectly influenced politics and law, war and peace, sexual morals, marriage and family life, toilet etiquette, letters and learning, the arts, economics, social justice, medical care and more.

Slaves and 'barbarians' did not have a full right to life and human sacrifices and gladiatorial combat were acceptable... Spartan Law required that deformed infants be put to death; for Plato, infanticide is one of the regular institutions of the ideal State; Aristotle regards abortion as a desirable option; and the Stoic philosopher Seneca writes unapologetically: "Unnatural progeny we destroy; we drown even children who at birth are weakly and abnormal... And whilst there were deviations from these views..., it is probably correct to say that such practices...were less proscribed in ancient times.

"[70]: 291 Daniel Washburn explains that the image of the mitered prelate braced in the door of the cathedral in Milan blocking Theodosius from entering, is a product of the imagination of Theodoret, a historian of the fifth century who wrote of the events of 390 "using his own ideology to fill the gaps in the historical record.

He examines three cases of "Christendom divided against itself": the crusades and St. Francis' attempt at peacemaking with Muslims; Spanish conquerors and the killing of indigenous peoples and the protests against it; and the on-again off-again persecution and protection of Jews.

But – We say with profound sorrow – there were to be found afterwards among the Faithful men who, shamefully blinded by the desire of sordid gain, in lonely and distant countries, did not hesitate to reduce to slavery Indians, negroes and other wretched peoples, or else, by instituting or developing the trade in those who had been made slaves by others, to favour their unworthy practice.

This began within 20 years of the discovery of the New World by Europeans in 1492 – in December 1511, Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican friar, openly rebuked the Spanish rulers of Hispaniola for their "cruelty and tyranny" in dealing with the American natives.

Heilbron,[222] A.C. Crombie, David Lindberg,[223] Edward Grant, historian of science Thomas Goldstein,[224] and Ted Davis, have argued that the Church had a significant, positive influence on the development of Western civilization.

They hold that, not only did monks save and cultivate the remnants of ancient civilization during the barbarian invasions, but that the Church promoted learning and science through its sponsorship of many universities which, under its leadership, grew rapidly in Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries.

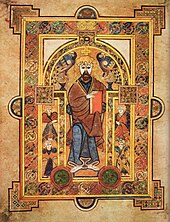

During the period of European history often called the Dark Ages which followed the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, Church scholars and missionaries played a vital role in preserving knowledge of Classical Learning.

[dubious – discuss] And our own world would never have come to be.According to art historian Kenneth Clark, for some five centuries after the fall of Rome, virtually all men of intellect joined the Church and practically nobody in western Europe outside of monastic settlements had the ability to read or write.

[270] The English science historian James Burke examines the impact of Cistercian waterpower, derived from Roman watermill technology such as that of Barbegal aqueduct and mill near Arles in the fourth of his ten-part Connections TV series, called "Faith in Numbers".

The Church's interest in astronomy began with purely practical concerns, when in the 16th century Pope Gregory XIII required astronomers to correct for the fact that the Julian calendar had fallen out of sync with the sky.

[284] In this most famous example cited by critics of the Catholic Church's "posture towards science", Galileo Galilei was denounced in 1633 for his work on the heliocentric model of the Solar System, previously proposed by the Polish clergyman and intellectual Nicolaus Copernicus.

[dubious – discuss] From now on the Scientific Revolution moved to Northern Europe.Pope John Paul II, on 31 October 1992, publicly expressed regret for the actions of those Catholics who badly treated Galileo in that trial.

These included Bulgaria, Serbia, and the Rus, as well as some non-Orthodox states like the Republic of Venice and the Kingdom of Sicily, which had close ties to the Byzantine Empire despite being in other respects part of western European culture.

Certain artistic traditions that originated in the Byzantine Empire, particularly in regard to icon painting and church architecture, are maintained in Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Russia and other Eastern Orthodox countries to the present day.

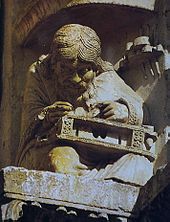

From 1100, he wrote, monumental abbeys and cathedrals were constructed and decorated with sculptures, hangings, mosaics and works belonging to one of the greatest epochs of art, providing stark contrast to the monotonous and cramped conditions of ordinary living during the period.

The Late Middle Ages produced ever more extravagant art and architecture, but also the virtuous simplicity of those such as St Francis of Assisi (expressed in the Canticle of the Sun) and the epic poetry of Dante's Divine Comedy.

[219]: 133 During both The Renaissance and the Counter-Reformation, Catholic artists produced many of the unsurpassed masterpieces of Western art – often inspired by Biblical themes: from Michelangelo's David and Pietà sculptures, to Da Vinci's Last Supper and Raphael's various Madonna paintings.

With a literary tradition spanning two millennia, the Bible and Papal Encyclicals have been constants of the Catholic canon but countless other historical works may be listed as noteworthy in terms of their influence on Western society.

From late Antiquity, St Augustine's book Confessions, which outlines his sinful youth and conversion to Christianity, is widely considered to be the first autobiography ever written in the canon of Western Literature.

In the late 18th century, Protestant merchant families began to move into banking to an increasing degree, especially in trading countries such as the United Kingdom (Barings, Lloyd),[310] Germany (Schroders, Berenbergs)[311] and the Netherlands (Hope & Co., Gülcher & Mulder).

[326] Episcopalians and Presbyterians tend to be considerably wealthier[313] and better educated (having more graduate and post-graduate degrees per capita) than most other religious groups in America,[328] and are disproportionately represented in the upper reaches of American business,[329] law and politics, especially the Republican Party.

[357] The Methodist Church, among other Christian denominations, was responsible for the establishment of hospitals, universities, orphanages, soup kitchens, and schools to follow Jesus's command to spread the Good News and serve all people.

[368] In Neyoor, the London Missionary Society Hospital "pioneered improvements in the public health system for the treatment of diseases even before organised attempts were made by the colonial Madras Presidency, reducing the death rate substantially".

Universities began springing up in Italian towns like Salerno, whose Schola Medica Salernitana, established in the 9th Century, became a leading medical school and translated the work of Greek and Arabic physicians into Latin.

[379] The medieval universities of Western Christendom were well-integrated across all of Western Europe, encouraged freedom of enquiry and produced a great variety of fine scholars and natural philosophers, including Robert Grosseteste of the University of Oxford, an early expositor of a systematic method of scientific experimentation;[381] and Saint Albert the Great, a pioneer of biological field research[382] In the 13th century, mendicant orders were founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic de Guzmán which brought consecrated religious life into urban settings.

[455] They were even hired by wealthy Persian merchants to travel to Europe when they wanted to create commercial bases there, and the Armenians eventually established themselves in cities like Bursa, Aleppo, Venice, Livorno, Marseilles and Amsterdam.