Climate of Mars

The climate of Mars has been a topic of scientific curiosity for centuries, in part because it is the only terrestrial planet whose surface can be easily directly observed in detail from Earth with help from a telescope.

While Mars's climate has similarities to Earth's, including periodic ice ages, there are also important differences, such as much lower thermal inertia.

Advanced Earth-orbital instruments today continue to provide some useful "big picture" observations of relatively large weather phenomena.

Data-based climate studies started in earnest with the Viking program landers in 1975 and continue with such probes as the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

This observational work has been complemented by a type of scientific computer simulation called the Mars general circulation model.

[7] Geomorphic observations of both landscape erosion rates[8] and Martian valley networks[9] also strongly imply warmer, wetter conditions on Noachian-era Mars (earlier than about four billion years ago).

However, chemical analysis of Martian meteorite samples suggests that the ambient near-surface temperature of Mars has most likely been below 0 °C (32 °F) for the last four billion years.

On September 29, 2008, the Phoenix lander detected snow falling from clouds 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) above its landing site near Heimdal Crater.

Later missions, starting with the dual Mariner 6 and 7 flybys, plus the Soviet Mars 2 and 3, carried infrared detectors to measure radiant energy.

[20] The missions could also corroborate these remote sensing datasets with not only their in situ lander metrology booms,[21] but with higher-altitude temperature and pressure sensors for their descent.

[34] The TES data indicates "Much colder (10–20 K) global atmospheric temperatures were observed during the 1997 versus 1977 perihelion periods" and "that the global aphelion atmosphere of Mars is colder, less dusty, and cloudier than indicated by the established Viking climatology," again, taking into account the Wilson and Richardson revisions to Viking data.

Typical daily temperature swings, away from the polar regions, are around 100 K. On Earth, winds often develop in areas where thermal inertia changes suddenly, such as from sea to land.

"[53] Those weaknesses are being corrected and should lead to more accurate future assessments, but make continued reliance on older predictions of modeled Martian climate somewhat problematic.

[57] Due to the low thermal inertia of Mars' thin CO2 atmosphere and the short radiative timescales, katabatic winds on Mars are two to three times stronger than those on Earth and take place on large areas of land with weak ambient winds, sloping terrain, and near-surface temperature inversions or radiative cooling of the surface and atmosphere.

[59] However, even when the seasonal cap has sublimated over the course of the Martian summer, the fast winds necessary for katabatic jumps are no longer present, meaning the cloud cover is again negligible.

Instruments on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter detected observed water vapor at very high altitudes during global dust storms.

[87] A large doughnut shaped cloud appears in the north polar region of Mars around the same time every Martian year and of about the same size.

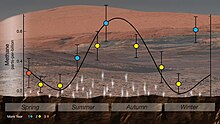

Trace amounts of methane, at the level of several parts per billion (ppb), were first reported in Mars' atmosphere by a team at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in 2003.

Four measurements taken over two months in this period averaged 7.2 ppb, implying that Mars is episodically producing or releasing methane from an unknown source.

Spring warming in certain areas leads to CO2 ice subliming and flowing upwards, creating highly unusual erosion patterns called "spider gullies".

In the spring and autumn wind due to the carbon dioxide sublimation process is so strong that it can be a cause of the global dust storms mentioned above.

[112] Both polar caps show spiral troughs, which were initially thought to form as a result of differential solar heating, coupled with the sublimation of ice and condensation of water vapor.

Both polar caps shrink and regrow following the temperature fluctuation of the Martian seasons; there are also longer-term trends that are better understood in the modern era.

As on Earth, Mars' obliquity dominates the seasons but, because of the large eccentricity, winters in the southern hemisphere are long and cold while those in the north are short and relatively warm.

[125] When the tilt begins to return to lower values, the ice sublimates (turns directly to a gas) and leaves behind a lag of dust.

Jacques Laskar, of France's National Centre for Scientific Research, argues that the effects of these periodic climate changes can be seen in the layered nature of the ice cap at the Martian north pole.

[citation needed] Colaprete et al. conducted simulations with the Mars General Circulation Model which show that the local climate around the Martian south pole may currently be in an unstable period.

The simulated instability is rooted in the geography of the region, leading the authors to speculate that the sublimation of the polar ice is a local phenomenon rather than a global one.

[142] The researchers showed that even with a constant solar luminosity the poles were capable of jumping between states of depositing or losing ice.

Notably, Elon Musk has suggested detonating nuclear weapons on the ice caps of Mars to release water vapor and carbon dioxide, which could warm the planet significantly enough to possibly make it habitable for humans, though it has been disputed by recent research.

( Mars Climate Sounder ; Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter )

(1:38; animation; 30 October 2018; file description )