Cold-air damming

Cold air damming, or CAD, is a meteorological phenomenon that involves a high-pressure system (anticyclone) accelerating equatorward east of a north-south oriented mountain range due to the formation of a barrier jet behind a cold front associated with the poleward portion of a split upper level trough.

These events are seen commonly in the northern Hemisphere across central and eastern North America, south of the Alps in Italy, and near Taiwan and Korea in Asia.

Cold air damming typically happens in the mid-latitudes as this region lies within the Westerlies, an area where frontal intrusions are common.

[1] Cold air damming is observed in the southern hemisphere to the east of the Andes, with cool incursions seen as far equatorward as the 10th parallel south.

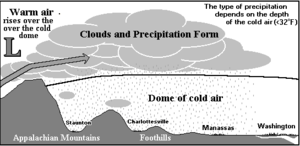

Other common instances of cold air damming take place on the coastal plain of east-central North America, between the Appalachian Mountains and Atlantic Ocean.

[9] The usual development of CAD is when a cool high-pressure area wedges in east of a north-south oriented mountain chain.

As a system approaches from the west, a persistent cloud deck with associated precipitation forms and lingers across the region for prolonged periods of time.

Temperature differences between the warmer coast and inland sections east of the terrain can exceed 36 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius), with rain near the coast and frozen precipitation, such as snow, sleet, and freezing rain, falling inland during colder times of the year.

[2] Cold air damming events which occur when the parent surface high-pressure system is relatively weak, with a central pressure below 1,028.0 millibars (30.36 inHg), or remaining a progressive feature (move consistently eastward), can be significantly enhanced by cloudiness and precipitation itself.

) evaluated for three mountain-normal lines constructed from surface observations in and around the area affected by the cold air damming—the damming region.

The Santa Ana is further complicated by down-sloped air, or foehn winds, drying out and warming up in the lee of the Sierra Nevada and coastal ranges, leading to a dangerous wildfire situation.

Small values of the Richardson number result in turbulent mixing that can weaken the inversion layer and aid the deterioration of the cold dome, leading to the end of the CAD event.

[9] In the United States, as a high-pressure system moves eastward out to the Atlantic, northerly winds are reduced along the southeast coast.

The reduction of cloud cover permits solar heating to effectively warm the cold dome from the surface up.

[9] The strong static stability of a CAD inversion layer usually inhibits turbulent mixing, even in the presence of vertical wind shear.

Classical CAD events are characterized by dry synoptic forcing, partial diabatic contribution, and a strong parent anticyclone (high-pressure system) located to the north of the Appalachian damming region.

[9] For diabatically enhanced classical events, at 24 hours prior to the onset of CAD, a prominent 250-mb jet extends from southwest to northeast across eastern North America.

The parent high-pressure system is centered over the upper Midwest beneath the 250-mb jet entrance region, setting up conditions for CAD east of the Rocky Mountains.

The center of the high-pressure system is farther east, so ridging extends southward into the south-central eastern United States.

[13] When the parent anticyclone is weaker or not ideally located, the diabatic process must start to contribute in order to develop CAD.

In scenarios where there is an equal contribution from dry synoptic forcing and diabatic processes, it is considered a hybrid damming event.

[9] The 250-mb jet is weaker and slightly farther south relative to a classical composite 24 hours prior to CAD onset.

These events occur during the absence of ideal synoptic conditions, when the anticyclone position is highly unfavorable located well offshore.

[9] In some in situ cases, the barrier pressure gradient is largely due to a cyclone to the southwest rather than the anticyclone to the northeast.