Combinatorics

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and as an end to obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures.

It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many applications ranging from logic to statistical physics and from evolutionary biology to computer science.

Many combinatorial questions have historically been considered in isolation, giving an ad hoc solution to a problem arising in some mathematical context.

In the later twentieth century, however, powerful and general theoretical methods were developed, making combinatorics into an independent branch of mathematics in its own right.

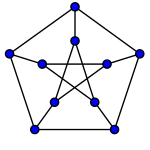

[2] One of the oldest and most accessible parts of combinatorics is graph theory, which by itself has numerous natural connections to other areas.

[6] Although primarily concerned with finite systems, some combinatorial questions and techniques can be extended to an infinite (specifically, countable) but discrete setting.

[7][8][9] Earlier, in the Ostomachion, Archimedes (3rd century BCE) may have considered the number of configurations of a tiling puzzle,[10] while combinatorial interests possibly were present in lost works by Apollonius.

[15] The philosopher and astronomer Rabbi Abraham ibn Ezra (c. 1140) established the symmetry of binomial coefficients, while a closed formula was obtained later by the talmudist and mathematician Levi ben Gerson (better known as Gersonides), in 1321.

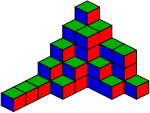

[16] The arithmetical triangle—a graphical diagram showing relationships among the binomial coefficients—was presented by mathematicians in treatises dating as far back as the 10th century, and would eventually become known as Pascal's triangle.

In the second half of the 20th century, combinatorics enjoyed a rapid growth, which led to establishment of dozens of new journals and conferences in the subject.

[19] In part, the growth was spurred by new connections and applications to other fields, ranging from algebra to probability, from functional analysis to number theory, etc.

These connections shed the boundaries between combinatorics and parts of mathematics and theoretical computer science, but at the same time led to a partial fragmentation of the field.

Analytic combinatorics concerns the enumeration of combinatorial structures using tools from complex analysis and probability theory.

It incorporates the bijective approach and various tools in analysis and analytic number theory and has connections with statistical mechanics.

The solution of the problem is a special case of a Steiner system, which play an important role in the classification of finite simple groups.

Structures analogous to those found in continuous geometries (Euclidean plane, real projective space, etc.)

Extremal combinatorics studies how large or how small a collection of finite objects (numbers, graphs, vectors, sets, etc.)

This approach (often referred to as the probabilistic method) proved highly effective in applications to extremal combinatorics and graph theory.

Thus the combinatorial topics may be enumerative in nature or involve matroids, polytopes, partially ordered sets, or finite geometries.

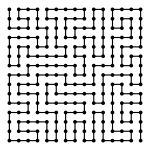

It has applications to enumerative combinatorics, fractal analysis, theoretical computer science, automata theory, and linguistics.

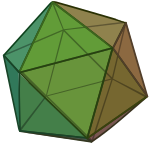

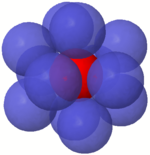

The study of regular polytopes, Archimedean solids, and kissing numbers is also a part of geometric combinatorics.

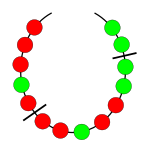

Combinatorial analogs of concepts and methods in topology are used to study graph coloring, fair division, partitions, partially ordered sets, decision trees, necklace problems and discrete Morse theory.

Some of the things studied include continuous graphs and trees, extensions of Ramsey's theorem, and Martin's axiom.

[23] Gian-Carlo Rota used the name continuous combinatorics[24] to describe geometric probability, since there are many analogies between counting and measure.

There remain many connections with geometric and topological combinatorics, which themselves can be viewed as outgrowths of the early discrete geometry.