Cree language

Cree (/kriː/ KREE;[4] also known as Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi) is a dialect continuum of Algonquian languages spoken by approximately 86,475 indigenous people across Canada in 2021,[5] from the Northwest Territories to Alberta to Labrador.

[5] The only region where Cree has any official status is in the Northwest Territories, alongside eight other aboriginal languages.

[8] Endonyms are: Cree is believed to have begun as a dialect of the Proto-Algonquian language spoken between 2,500 and 3,000 years ago in the original Algonquian homeland, an undetermined area thought to be near the Great Lakes.

The speakers of the proto-Cree language are thought to have moved north, and diverged rather quickly into two different groups on each side of James Bay.

[9] After this point it is very difficult to make definite statements about how different groups emerged and moved around, because there are no written works in the languages to compare, and descriptions by Europeans are not systematic; as well, Algonquian people have a tradition of bilingualism and even of outright adopting a new language from neighbours.

By contrast, James Smith of the Museum of the American Indian stated, in 1987, that the weight of archeological and linguistic evidence puts the Cree as far west as the Peace River Region of Alberta before European contact.

For practical purposes, Cree usually covers the dialects which use syllabics as their orthography (including Atikamekw but excluding Kawawachikamach Naskapi), the term Montagnais then applies to those dialects using the Latin script (excluding Atikamekw and including Kawawachikamach Naskapi).

Roughly from west to east: This table shows the possible consonant phonemes in the Cree language or one of its varieties.

Eastern James Bay Cree prefers to indicate long vowels (other than [eː]) by doubling the vowel, while the western Cree use either a macron or circumflex diacritic; as [eː] is always long, often it is written as just ⟨e⟩ without doubling or using a diacritic.

A common grammatical feature in Cree dialects, in terms of sentence structure, is non-regulated word order.

Word order is not governed by a specific set of rules or structure; instead, "subjects and objects are expressed by means of inflection on the verb".

In a sense, the obviative can be defined as any third-person ranked lower on a hierarchy of discourse salience than some other (proximate) discourse-participant.

[15] The Cree language has grammatical gender in a system that classifies nouns as animate or inanimate.

Instead, either a full-stop glyph (⟨᙮⟩) or a double em-width space has been used between words to signal the transition from one sentence to the next.

[21]: 5 For more details on the phonetic values of these letters or variant orthographies, see the § Phonology section above.

[21]: 24–25 There are additional rules regarding h and iy that may not match a given speaker's speech, to enable a standardized transcription.

Michif and Bungi are spoken by members of the Métis, and historically by some Voyageurs and European settlers of Western Canada and in parts of the Northern United States.

For the most part, Michif uses Cree verbs, question words, and demonstratives while using French nouns.

Michif is unique to the Canadian prairie provinces as well as to North Dakota and Montana in the United States.

This language flourished at and around the Red River Settlement (the modern-day location of Winnipeg, Manitoba) by the mid- to late-1800s.

[29] Doug Cuthand argues three reasons for the loss of the Cree language among many speakers over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Cuthand also argues that the loss of the Cree language can be attributed to the migration of native families away from the reserve, voluntarily or not.

The third point Cuthand[30] argues is that Cree language loss was adopted by the speakers.

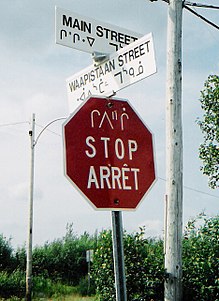

Cree is one of the eleven official languages of the Northwest Territories, but is only spoken by a small number of people there in the area around the town of Fort Smith.

[7] It is also one of two principal languages of the regional government of Eeyou Istchee James Bay in Northern Quebec, the other being French.

He was instrumental in obtaining unanimous consent from all political parties to change the standing orders to allow Indigenous languages to be spoken in the House of Commons, with full translation services provided.

Ouellette was the chair of the Indigenous caucus in the House of Commons and helped ensure it passage before the election of 2019.

They are working on broadcasting a radio station that "will give listeners music and a voice for our languages".