Cross-bedding

Examples of these bedforms are ripples, dunes, antidunes, sand waves, hummocks, bars, and delta slopes.

[1] Environments in which water movement is fast enough and deep enough to develop large-scale bed forms fall into three natural groupings: rivers, tide-dominated coastal and marine settings.

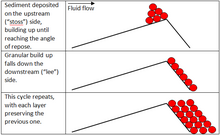

The fluid flow causes sand grains to saltate up the stoss (upstream) side of the bedform and collect at the peak until the angle of repose is reached.

At this point, the crest of granular material has grown too large and will be overcome by the force of the moving water, falling down the lee(downstream) side of the dune.

Individual cross-beds can range in thickness from just a few tens of centimeters, up to hundreds of feet or more depending upon the depositional environment and the size of the bedform.

It is most common in stream deposits (consisting of sand and gravel), tidal areas, and in aeolian dunes.

[6] Where the set height is less than 6 centimeters and the cross-stratification layers are only a few millimeters thick, the term cross-lamination is used, rather than cross-bedding.

[8] Trough cross-beds have lower surfaces which are curved or scoop shaped and truncate the underlying beds.

[9] The shape of the grains and the sorting and composition of sediment can provide additional information on the history of cross-beds.

For example: well-rounded, and well-sorted sand that is mostly composed of quartz grains is commonly found in beach environments, far from the source of the sediment.

Thus, a river may well erode an older formation of well-rounded, well-sorted beach sands of nearly pure quartz.

Discharge variations measured on a variety of time scales can change water depth, and speed.

Others are dominated by durational variations characteristic of alpine glaciers run-off or random storm events, which produce flashy discharge.

Their presence and morphologic variability have been related to flow strength expressed as mean velocity or shear stress.

The temporal and spatial variability of flow and sediment transport, coupled with regular fluctuating water levels creates a variety of bed form morphology.

[2] In an aeolian environment, cross-beds often exhibit inverse grading due to their deposition by grain flows.