Crystal

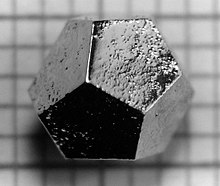

[1][2] In addition, macroscopic single crystals are usually identifiable by their geometrical shape, consisting of flat faces with specific, characteristic orientations.

For example, when liquid water starts freezing, the phase change begins with small ice crystals that grow until they fuse, forming a polycrystalline structure.

Most macroscopic inorganic solids are polycrystalline, including almost all metals, ceramics, ice, rocks, etc.

The symmetry of a crystal is constrained by the requirement that the unit cells stack perfectly with no gaps.

There are 219 possible crystal symmetries (230 is commonly cited, but this treats chiral equivalents as separate entities), called crystallographic space groups.

Crystals are commonly recognized, macroscopically, by their shape, consisting of flat faces with sharp angles.

By volume and weight, the largest concentrations of crystals in the Earth are part of its solid bedrock.

[12] Some crystals have formed by magmatic and metamorphic processes, giving origin to large masses of crystalline rock.

The vast majority of igneous rocks are formed from molten magma and the degree of crystallization depends primarily on the conditions under which they solidified.

Such rocks as granite, which have cooled very slowly and under great pressures, have completely crystallized; but many kinds of lava were poured out at the surface and cooled very rapidly, and in this latter group a small amount of amorphous or glassy matter is common.

This means that they were at first fragmental rocks like limestone, shale and sandstone and have never been in a molten condition nor entirely in solution, but the high temperature and pressure conditions of metamorphism have acted on them by erasing their original structures and inducing recrystallization in the solid state.

Evaporites such as halite, gypsum and some limestones have been deposited from aqueous solution, mostly owing to evaporation in arid climates.

Chocolate can form six different types of crystals, but only one has the suitable hardness and melting point for candy bars and confections.

Polymorphism in steel is responsible for its ability to be heat treated, giving it a wide range of properties.

Crystallization is a complex and extensively-studied field, because depending on the conditions, a single fluid can solidify into many different possible forms.

It can form a single crystal, perhaps with various possible phases, stoichiometries, impurities, defects, and habits.

Conversely, some organisms have special techniques to prevent crystallization from occurring, such as antifreeze proteins.

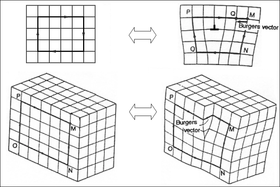

[19] However, in reality, most crystalline materials have a variety of crystallographic defects: places where the crystal's pattern is interrupted.

Likewise, the only difference between ruby and sapphire is the type of impurities present in a corundum crystal.

In semiconductors, a special type of impurity, called a dopant, drastically changes the crystal's electrical properties.

But unlike a grain boundary, the orientations are not random, but related in a specific, mirror-image way.

A mosaic crystal consists of smaller crystalline units that are somewhat misaligned with respect to each other.

[20] Ionic compounds typically form when a metal reacts with a non-metal, such as sodium with chlorine.

[21] Weak van der Waals forces also help hold together certain crystals, such as crystalline molecular solids, as well as the interlayer bonding in graphite.

They have many attributes in common with ordinary crystals, such as displaying a discrete pattern in x-ray diffraction, and the ability to form shapes with smooth, flat faces.

Quasicrystals are most famous for their ability to show five-fold symmetry, which is impossible for an ordinary periodic crystal (see crystallographic restriction theorem).

[25] Crystals can have certain special electrical, optical, and mechanical properties that glass and polycrystals normally cannot.

These properties are related to the anisotropy of the crystal, i.e. the lack of rotational symmetry in its atomic arrangement.

They can appear in glasses or polycrystals that have been made anisotropic by working or stress—for example, stress-induced birefringence.