Curtin–Hammett principle

When the rate of interconversion between A and B is much faster than either k1 or k2, then the Curtin–Hammett principle tells us that the C:D product ratio is not equal to the equilibrium A:B reactant ratio, but is instead determined by the relative energies of the transition states (i.e., difference in the absolute energies of the transition states).

[5] The rate of formation for compound C from A is given as and that of D from B as with the second approximate equality following from the assumption of rapid equilibration.

In the case of N-methyl piperidine, inversion at nitrogen between diastereomeric conformers is much faster than the rate of amine oxidation.

An important implication is that the product of a reaction can be derived from a conformer that is at sufficiently low concentration as to be unobservable in the ground state.

[3] The alkylation of tropanes with methyl iodide is a classic example of a Curtin–Hammett scenario in which a major product can arise from a less stable conformation.

[clarification needed] It is hypothetically possible that two different conformers in equilibrium could react through transition states that are equal in energy.

For instance, high selectivity for one ground state conformer is observed in the following radical methylation reaction.

[11] The conformer in which A(1,3) strain is minimized is at an energy minimum, giving 99:1 selectivity in the ground state.

However, transition state energies depend both on the presence of A(1,3) strain and on steric hindrance associated with the incoming methyl radical.

[13] Rapid equilibration between enantiomeric conformers and irreversible hydrogenation place the reaction under Curtin–Hammett control.

[14] Consistent with the Curtin–Hammett principle, the ratio of products depends on the absolute energetic barrier of the irreversible step of the reaction, and does not reflect the equilibrium distribution of substrate conformers.

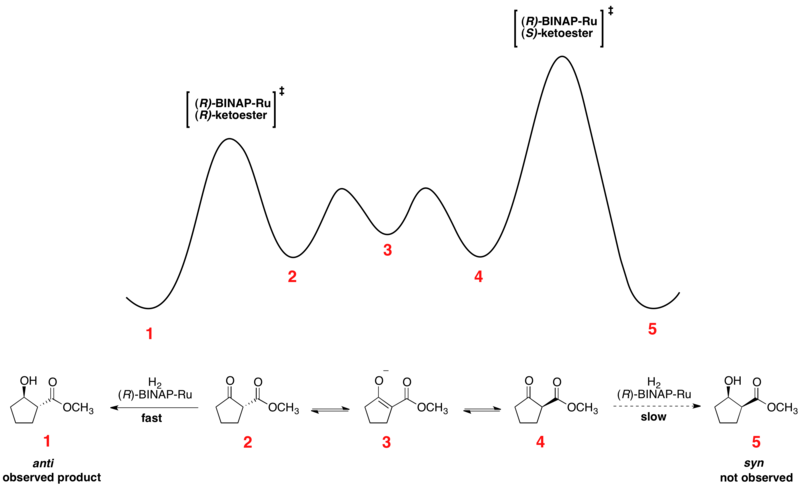

The relative free energy profile of one example of the Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation is shown below: Dynamic kinetic resolution under Curtin–Hammett conditions has also been applied to enantioselective lithiation reactions.

[13] Equilibration between the two alkyllithium complexes was demonstrated by the observation that enantioselectivity remained constant over the course of the reaction.

Were the two reactant complexes not rapidly interconverting, enantioselectivity would erode over time as the faster-reacting conformer was depleted.

Ordinarily, the less-hindered site of an asymmetric 1,2-diol would experience more rapid esterification due to reduced steric hindrance between the diol and the acylating reagent.

Developing a selective esterification of the most substituted hydroxyl group is a useful transformation in synthetic organic chemistry, particularly in the synthesis of carbohydrates and other polyhydroxylated compounds.

However, allowing the two isomers to equilibrate results in an excess of the more stable primary alkoxy stannane in solution.

One example is observed en route to the antitumor antibiotic AT2433-A1, in which a Mannich-type cyclization proceeds with excellent regioselectivity.

Studies demonstrate that the cyclization step is irreversible in the solvent used to run the reaction, suggesting that Curtin–Hammett kinetics can explain the product selectivity.

[18] A Curtin–Hammett scenario was invoked to explain selectivity in the syntheses of kapakahines B and F, two cyclic peptides isolated from marine sponges.

[19] A key step in the syntheses is selective amide bond formation to produce the correct macrocycle.

In Phil Baran's enantioselective synthesis of kapakahines B and F, macrocycle formation was proposed to occur via two isomers of the substrate.

However, because the amide-bond-forming step was irreversible and the barrier to isomerization was low, the major product was derived from the faster-reacting intermediate.

A key step in the synthesis is the rhodium-catalyzed formation of an oxonium ylide, which then undergoes a [2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement en route to the desired product.

Obtaining high selectivity for the desired product was possible, however, due to differences in the activation barriers for the step following ylide formation.

If the ortho-methoxy group undergoes oxonium ylide formation, a 1,4-methyl shift can then generate an undesired product.

The oxonium ylide formed from the other ortho-alkoxy group is primed to undergo a [2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement to yield the desired compound.

The symmetry-allowed [2,3] sigmatropic rearrangement must follow a pathway that is lower in activation energy than the 1,4-methyl shift, explaining the exclusive formation of the desired product.

The reaction provided good selectivity for the desired isomer, with results consistent with a Curtin-Hammett scenario.

Reductive elimination is favored from the more reactive, less stable intermediate, as strain relief is maximized in the transition state.