Roman calendar

It is possible the original calendar was agriculturally based, observational of the seasons and stars rather than of the moon, with ten months of varying length filling the entire year.

If this ever existed, it would have changed to the lunisolar system later credited to Numa during the kingdom or early Republic under the influence of the Etruscans and of Pythagorean Southern Italian Greeks.

By the 191 BC Lex Acilia or before, control of intercalation was given to the pontifex maximus but—as these were often active political leaders like Caesar—political considerations continued to interfere with its regular application.

Victorious in civil war, Caesar reformed the calendar in 46 BC, coincidentally making the year of his third consulship last for 446 days.

[6] She considers that this more sensibly accounts for later legends of Romulus's decimal year and the great irregularity in Italian month lengths recorded in Censorinus.

[6][7] Roman works on agriculture including those of Cato,[8] Varro,[9] Vergil,[10] Columella,[11] and Pliny[12] invariably date their practices based on suitable conditions or upon the rising of stars, with only occasional supplementary mention of the civil calendar of their times[6] until the 4th or 5th century author Palladius.

[21][22] Licinius Macer's lost history apparently similarly stated that even the earliest Roman calendar employed intercalation.

[23][24][25] Later Roman writers usually credited this calendar to Romulus,[26][27] their legendary first king and culture hero, although this was common with other practices and traditions whose origin had been lost to them.

Some scholars doubt the existence of this calendar at all, as it is only attested in late Republican and Imperial sources and supported only by the misplaced names of the months from September to December.

Plutarch's Parallel Lives recounts that Romulus's calendar had been solar but adhered to the general principle that the year should last for 360 days.

[32][33] Plutarch records that while one tradition is that Numa added two new months to a ten-month calendar, another version is that January and February were originally the last two months of the year and Numa just moved them to the start of the year, so that January (named after a peaceful ruler called Janus) would come before March (which was named for Mars, the god of war).

[42][43] W. Warde Fowler believed the Roman priests continued to treat January and February as the last months of the calendar throughout the Republican period.

Julius Caesar, following his victory in his civil war and in his role as pontifex maximus, ordered a reformation of the calendar in 46 BC.

After Antony's defeat at Actium, Augustus assumed control of Rome and, finding the priests had (owing to their inclusive counting) been intercalating every third year instead of every fourth, suspended the addition of leap days to the calendar for one or two decades until its proper position had been restored.

Diocletian began the 15-year indiction cycles beginning from the AD 297 census;[47] these became the required format for official dating under Justinian.

[47] The Roman method of numbering the days of the month never became widespread in the Hellenized eastern provinces and was eventually abandoned by the Byzantine Empire in its calendar.

The patricians and their clients sometimes exploited this fact as a kind of filibuster, since the tribunes of the plebs were required to wait another three-week period if their proposals could not receive a vote before dusk on the day they were introduced.

The 7-day week began to be observed in Italy in the early imperial period,[62] as practitioners and converts to eastern religions introduced Hellenistic and Babylonian astrology, the Jewish Saturday sabbath, and the Christian Lord's Day.

The system was originally used for private worship and astrology but had replaced the nundinal week by the time Constantine made Sunday (dies Solis) an official day of rest in AD 321.

Some of their etymologies are well-established: January and March honor the gods Janus[63] and Mars;[64] July and August honor Julius Caesar[65] and his successor, the emperor Augustus;[66] and the months Quintilis,[67] Sextilis,[68] September,[69] October,[70] November,[71] and December[72] are archaic adjectives formed from the ordinal numbers from 5 to 10, their position in the calendar when it began around the spring equinox in March.

The Republican calendar only had 355 days, which meant that it would quickly unsynchronize from the solar year, causing, for example, agricultural festivals to occur out of season.

As mentioned above, Rome's legendary 10-month calendar notionally lasted for 304 days but was usually thought to make up the rest of the solar year during an unorganized winter period.

Some historians of the later republic and early imperial eras dated from the legendary founding of the city of Rome (ab urbe condita or AVC).

[47] These cycles were not distinguished, however, so that "year 2 of the indiction" may refer to any of 298, 313, 328, &c.[47] The Orthodox subjects of the Byzantine Empire used various Christian eras, including those based on Diocletian's persecutions, Christ's incarnation, and the supposed age of the world.

The Romans did not have records of their early calendars but, like modern historians, assumed the year originally began in March on the basis of the names of the months following June.

The consul M. Fulvius Nobilior (r. 189 BC) wrote a commentary on the calendar at his Temple of Hercules Musarum that claimed January had been named for Janus because the god faced both ways,[83][where?]

Even following the establishment of the Julian calendar, the leap years were not applied correctly by the Roman priests, meaning dates are a few days out of their "proper" place until a few decades into Augustus's reign.

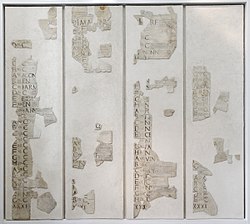

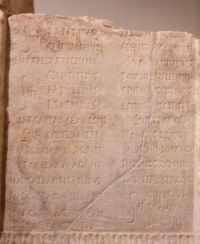

Given the paucity of records regarding the state of the calendar and its intercalation, historians have reconstructed the correspondence of Roman dates to their Julian and Gregorian equivalents from disparate sources.

There are detailed accounts of the decades leading up to the Julian reform, particularly the speeches and letters of Cicero, which permit an established chronology back to about 58 BC.

The nundinal cycle and a few known synchronisms—e.g., a Roman date in terms of the Attic calendar and Olympiad—are used to generate contested chronologies back to the start of the First Punic War in 264 BC.