Disinformation

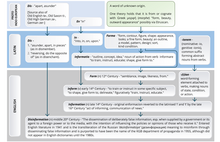

Disinformation is misleading content deliberately spread to deceive people,[1][2] or to secure economic or political gain and which may cause public harm.

[3] Disinformation is an orchestrated adversarial activity in which actors employ strategic deceptions and media manipulation tactics to advance political, military, or commercial goals.

[4] Disinformation is implemented through attacks that "weaponize multiple rhetorical strategies and forms of knowing—including not only falsehoods but also truths, half-truths, and value judgements—to exploit and amplify culture wars and other identity-driven controversies.

[11][12][13][14] Some consider it a loan translation of the Russian дезинформация, transliterated as dezinformatsiya,[15][1][2] apparently derived from the title of a KGB black propaganda department.

[29] Similarly, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace proposed adding Degree ("distribution of the content ... and the audiences it reaches") and Effect ("how much of a threat a given case poses").

[47] The United States Intelligence Community appropriated use of the term disinformation in the 1950s from the Russian dezinformatsiya, and began to use similar strategies[61][62] during the Cold War and in conflict with other nations.

[17] Reuters noted a former U.S. intelligence officer said they would attempt to gain the confidence of reporters and use them as secret agents, to affect a nation's politics by way of their local media.

[17] In October 1986, the term gained increased currency in the U.S. when it was revealed that two months previously, the Reagan Administration had engaged in a disinformation campaign against then-leader of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi.

[63] White House representative Larry Speakes said reports of a planned attack on Libya as first broken by The Wall Street Journal on August 25, 1986, were "authoritative", and other newspapers including The Washington Post then wrote articles saying this was factual.

[63] U.S. State Department representative Bernard Kalb resigned from his position in protest over the disinformation campaign, and said: "Faith in the word of America is the pulse beat of our democracy.

[64] Pope Francis condemned disinformation in a 2016 interview, after being made the subject of a fake news website during the 2016 U.S. election cycle which falsely claimed that he supported Donald Trump.

[74][75] The call to formally classify disinformation as a cybersecurity threat is made by advocates due to its increase in social networking sites.

Techniques reported on included the use of bots to amplify hate speech, the illegal harvesting of data, and paid trolls to harass and threaten journalists.

[82] Cass Sunstein supported this in #Republic, arguing that the internet would become rife with echo chambers and informational cascades of misinformation leading to a highly polarized and ill-informed society.

For example, a double blind randomized-control experiment by researchers from the London School of Economics (LSE), found that exposure to online fake news about either Trump or Clinton had no significant effect on intentions to vote for those candidates.

Finally, they find "no evidence of a meaningful relationship between exposure to the Russian foreign influence campaign and changes in attitudes, polarization, or voting behavior.

"[85] As such, despite its mass dissemination during the 2016 Presidential Elections, online fake news or disinformation probably did not cost Hillary Clinton the votes needed to secure the presidency.

[92][93][94][95] Researchers have criticized the framing of disinformation as being limited to technology platforms, removed from its wider political context and inaccurately implying that the media landscape was otherwise well-functioning.

[112] Online advertising technologies have been used to amplify disinformation due to the financial incentives and monetization of user-generated content and fake news.