Dysosmia

[3] Most cases are described as idiopathic and the main antecedents related to parosmia are URTIs, head trauma, and nasal and paranasal sinus disease.

[1] Smell disorders can result in the inability to detect environmental dangers such as gas leaks, toxins, or smoke.

There is a loss of appetite because of unpleasant flavor and fear of failing to recognize and consuming spoiled food.

[6] Under an alternative definition, cacosmia is used for an unpleasant perception of an odorant due specifically to nasosinusal or pharyngeal infection.

In parosmia, the peripheral theory refers to the inability to form a complete picture of an odorant due to the loss of functioning olfactory receptor neurons.

The central theory refers to integrative centers in the brain forming a distorted odor.

The central theory for phantosmia is described as an area of hyper-functioning brain cells that generate the order perception.

Common triggers include gasoline, tobacco, coffee, perfume, fruits and chocolate.

[4] The cause of dysosmia has not been determined but there have been clinical associations with the neurological disorder:[2][8] Most of cases are described as idiopathic and the main antecedents related to parosmia are URTIs, head trauma, and nasal and paranasal sinus disease.

[4] Psychiatric causes for smell distortion can exist in schizophrenia, alcoholic psychosis, depression, and olfactory reference syndrome.

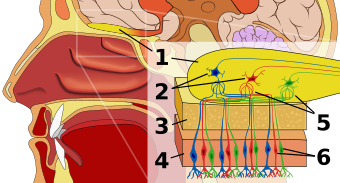

[5] There are approximately 6 million bipolar sensory receptor neurons whose cell bodies and dendrites are in the epithelium.

The axons of these cells aggregate into 30-40 fascicles, called the olfactory fila, which project through the cribriform plate and pia matter.

These axons collectively make up the olfactory nerve (CN I) and serve the purpose of mediating the sense of smell.

Its first neuron characteristic allows direct exposure to the environment, which makes the brain vulnerable to infection and invasion of xenobiotic agents.

The terminals of the receptor axons synapse with the dendrites of mitral and tufts cells within the glomeruli of the olfactory bulb.

A clinical history can also help determine what kind of dysosmia one has, as events such as respiratory infection and head trauma are usually indications of parosmia.

Options include a bifrontal craniotomy and excision of the olfactory epithelium, which cuts all of the fila olfactoria.

[1] According to some studies, transnasal endoscopic excision of the olfactory epithelium has been described as a safe and effective phantosmia treatment.

Parosmia has been estimated to be in 10-60% of patients with olfactory dysfunction and from studies, it has been shown that it can last anywhere from 3 months to 22 years.