Earthquake forecasting

In addition to specification of time, location, and magnitude, Allen suggested three other requirements: 4) indication of the author's confidence in the prediction, 5) the chance of an earthquake occurring anyway as a random event, and 6) publication in a form that gives failures the same visibility as successes.

In the 1970s, scientists were optimistic that a practical method for predicting earthquakes would soon be found, but by the 1990s continuing failure led many to question whether it was even possible.

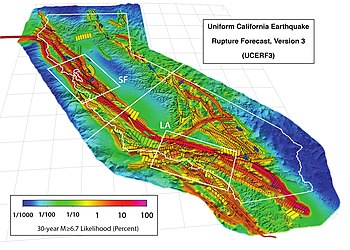

Such estimates are used to establish building codes, insurance rate structures, awareness and preparedness programs, and public policy related to seismic events.

[5] In addition to regional earthquake forecasts, such seismic hazard calculations can take factors such as local geological conditions into account.

Given a large force (such as between two immense tectonic plates moving past each other) the Earth's crust will bend or deform.

According to the elastic rebound theory of Reid (1910), eventually the deformation (strain) becomes great enough that something breaks, usually at an existing fault.

Since continuous plate motions cause the strain to accumulate steadily, seismic activity on a given segment should be dominated by earthquakes of similar characteristics that recur at somewhat regular intervals.

[11] For a given fault segment, identifying these characteristic earthquakes and timing their recurrence rate (or conversely return period) should therefore inform us about the next rupture; this is the approach generally used in forecasting seismic hazard.

It provides authoritative estimates of the likelihood and severity of potentially damaging earthquake ruptures in the long- and near-term.