Elastic-rebound theory

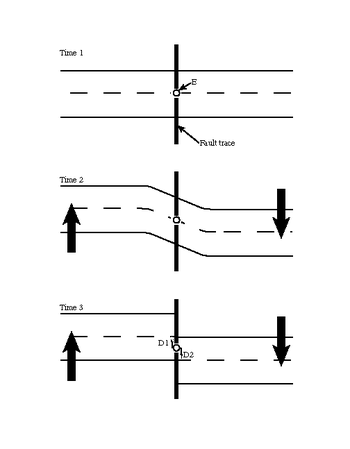

Then they separate with a rupture along the fault; the sudden movement releases accumulated energy, and the rocks snap back almost to their original shape.

The previously solid mass is divided between the two slowly moving plates, the energy released through the surroundings in a seismic wave.

Later measurements using the global positioning system largely support Reid's theory as the basis of seismic movement.

The two sides of an active but locked fault are slowly moving in different directions, where elastic strain energy builds up in any rock mass that adjoins them.

When the accumulated strain is great enough to overcome the strength of the rocks, the result is a sudden break, or a springing back to the original shape as much as possible, a jolt which is felt on the surface as an earthquake.