San Andreas Fault

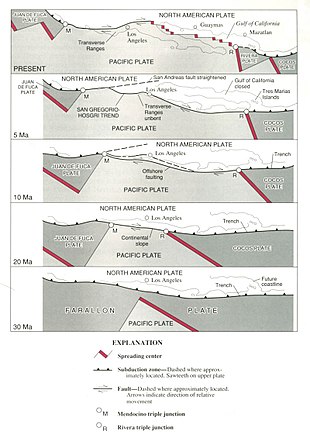

[1] In the north, the fault terminates offshore near Eureka, California, at the Mendocino triple junction, where three tectonic plates meet.

In this region, the Salton Trough), the plate boundary has been rifting and pulling apart, creating a new mid-ocean ridge that is an extension of the Gulf of California.

When the location of these offsets were plotted on a map, he noted that they made a near perfect line on top of the fault he previously discovered.

The aim was to collect core samples and make direct geophysical and geochemical observations to better understand fault behavior at depth.

[6] The northern segment of the fault runs from Hollister, through the Santa Cruz Mountains, epicenter of the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, then up the San Francisco Peninsula, where it was first identified by Professor Lawson in 1895, then offshore at Daly City near Mussel Rock.

From Fort Ross, the northern segment continues overland, forming in part a linear valley through which the Gualala River flows.

Such a large earthquake on this southern segment would kill thousands of people in Los Angeles, San Bernardino, Riverside, and surrounding areas, and cause hundreds of billions of dollars in damage.

This has led to the formation of the Transverse Ranges in Southern California, and to a lesser but still significant extent, the Santa Cruz Mountains (the location of the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989).

The rest of the motion has been found in an area east of the Sierra Nevada mountains called the Walker Lane or Eastern California Shear Zone.

One hypothesis – which gained interest following the Landers earthquake in 1992 – suggests the plate boundary may be shifting eastward away from the San Andreas towards Walker Lane.

This complicated evolution, especially along the southern segment, is mostly caused by either the "Big Bend" and/or a difference in the motion vector between the plates and the trend of the fault and its surrounding branches.

The fault was first identified in Northern California by UC Berkeley geology professor Andrew Lawson in 1895 and named by him after the surrounding San Andreas valley.

Large-scale (hundreds of miles) lateral movement along the fault was first proposed in a 1953 paper by geologists Mason Hill and Thomas Dibblee.

[16] Seismologists discovered that the San Andreas Fault near Parkfield in central California consistently produces a magnitude 6.0 earthquake approximately once every 22 years.

The goal of SAFOD is to drill a hole nearly 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) into the Earth's crust and into the San Andreas Fault.

[17] A 2023 study found a link between the water level in Lake Cahuilla (now the Salton Sea) and seismic activity along the southern San Andreas Fault.

The hydrological load caused by high water levels can more than double the stress on the southern San Andreas Fault, which is likely sufficient for triggering earthquakes.

[19] A study published in 2006 in the journal Nature by Yuri Fialko, an associate professor at the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics at Scripps Institution of Oceanography,[21] found that the San Andreas fault has reached a sufficient stress level for an earthquake of magnitude greater than 7.0 on the moment magnitude scale to occur.

[21]Nevertheless, in the 18 years since that publication there has not been a substantial quake in the Los Angeles area, and two major reports issued by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) have made variable predictions as to the risk of future seismic events.

That study predicted that a magnitude 7.8 earthquake along the southern San Andreas Fault could cause about 1,800 deaths and $213 billion in damage.

It was developed for preparedness geared towards Bay Area residents and as a warning with an attempt to encourage local policy makers to create infrastructure and protections that would further risk reduction and resilience-building.

[27] As of the 2021 Fact sheet update, there are several estimates on damages ranging from the approximate people affected at home, work, effects of lifeline infrastructures such as telecommunications, and more.

This group of scientists have worked together to create estimates of how hazards such as liquefaction, landslides, and fire ignition will impact access to utilities, transportation, and general emergency services.

However the 1906 San Francisco earthquake seems to have been the exception to this correlation because the plate movement was mostly from south to north and it was not preceded by a major quake in the Cascadia zone.