Economic history of France

The economic history of France involves major events and trends, including the elaboration and extension of the seigneurial economic system (including the enserfment of peasants) in the medieval Kingdom of France, the development of the French colonial empire in the early modern period, the wide-ranging reforms of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Era, the competition with the United Kingdom and other neighboring states during industrialization and the extension of imperialism, the total wars of the late-19th and early 20th centuries, and the introduction of the welfare state and integration with the European Union since World War II.

The economy relied heavily on agriculture, trade, and the production of luxury goods, and the power and influence of the monarchy played a significant role in shaping economic policies and development.

The Pirenne hypotheses posits that this disruption brought an end to long-distance trade, without which civilization retreated to purely agricultural settlements, and isolated military, church, and royal centers.

The French and English armies during the Hundred Years War marched back and forth across the land; they ransacked and burned towns, drained the food supply, disrupted agriculture and trade, and left disease and famine in their wake.

In subsequent decades, English, Dutch and Flemish maritime activity would create competition with French trade, which would eventually displace the major markets to the northwest, leading to the decline of Lyon.

By the middle of the 16th century, France's demographic growth, its increased demand for consumer goods, and its rapid influx of gold and silver from Africa and the Americas led to inflation (grain became five times as expensive from 1520 to 1600), and wage stagnation.

Henry IV attacked abuses, embarked on a comprehensive administrative reform, increased charges for official offices, the "paulette", repurchased alienated royal lands, improved roads and funded the construction of canals, and planted the seed of a state-supervised mercantile philosophy.

[8] Louis XIV's minister of finances, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, started a mercantile system which used protectionism and state-sponsored manufacturing to promote the production of luxury goods over the rest of the economy.

Meanwhile, wealthy families with stocks of grains survived relatively unscathed; in 1689 and again in 1709, in a gesture of solidarity with his suffering people, Louis XIV had his royal dinnerware and other objects of gold and silver melted down.

Initially a great success, the bank's pursuit of French monopolies led it to land speculation in Louisiana through the Mississippi Company, forming an economic bubble in the process that eventually burst in 1720.

[19] In 1726, under Louis XV's minister Cardinal Fleury, a system of monetary stability was put in place, leading to a strict conversion rate between gold and silver, and set values for the coins in circulation in France.

[22] Cádiz was the commercial hub for export of French printed fabrics to India, the Americas and the Antilles (coffee, sugar, tobacco, American cotton), and Africa (the slave trade), centered in Nantes.

[41] Crouzet argues that the average size of industrial undertakings was smaller in France than in other advanced countries; that machinery was generally less up to date, productivity lower, costs higher.

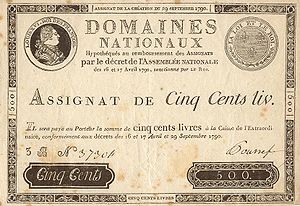

For those nobles who remained in France, the heated anti-aristocratic social environment dictated more modest patterns of dress and consumption, while the spiraling inflation of the assignats dramatically reduced their buying power.

The wartime exigencies enacted that year by the National Convention worsened the situation by banning the export of essential goods and embargoing neutral shipping from entering French ports.

Production of armaments and other military supplies, fortifications, and the general channeling of the society toward establishing and maintaining massed armies, temporarily increased economic activity after several years of revolution.

[79] The entrepreneur Aristide Boucicaut in 1852 took Au Bon Marché, a small shop in Paris, set fixed prices (with no need to negotiate with clerks), and offered guarantees that allowed exchanges and refunds.

The solution was a narrow base of funding through the Rothschilds and the closed circles of the Bourse in Paris, so France did not develop the same kind of national stock exchange that flourished in London and New York.

Scourges like the Great French Wine Blight, caused by the Phylloxera insect, and the parasitic disease known as pébrine which affected silkworms and the silk industry, made the depression of 1882 worse and more prolonged.

[121] Other factors contributing to the length and seriousness of the depression were the debt defaults of a number of foreign governments, railway company bankruptcies, a trade war between Italy and France between 1887 and 1898, new French tariffs on imports, and the general adoption of protectionism throughout the world.

[150] Furthermore, terminating fixed exchange rate regimes opened up opportunities for expansive monetary policy and thus influenced consumers’ expectations of future inflation, which was crucial for domestic demand.

[151] However, the depression had some effects on the local economy, and partly explains the February 6, 1934 riots and even more the formation of the Popular Front, led by SFIO socialist leader Léon Blum, which won the elections in 1936.

The strikes were spontaneous and unorganized, but nevertheless the business community panicked and met secretly with Blum, who negotiated a series of reforms, and then gave labor unions the credit for the Matignon Accords.

Alternating policies of "interventionist" and "free market" ideas enabled the French to build a society in which both industrial and technological advances could be made but also worker security and privileges were also established and protected.

[173] In 1945, the provisional government of the French Republic, led by Charles de Gaulle and made up of communists, socialists and gaullists, nationalized key economic sectors (energy, air transport, savings banks, assurances) and big companies (e.g. Renault), with the creation of Social Security and of works councils.

[186] The state was concerned with stimulating continuous modernization and restructuring, which it encouraged through communication improvements, tax policy, export credits, and ensuring access to cheap loans for firms.

The third Modernization Plan of 1957-1961 put an emphasis on investing in the staple agricultural products of Northern France and the Paris region: meat, milk, cheese, wheat, and sugar.

By 1978, France was the world leader in per capita ownership of second homes and L’Express reported an "irresistible infatuation of the French for the least Norman thatched house, Cévenol sheep barn or the most modest Provençal farmhouse.

However, after 2005 the world economy stagnated and the 2008 global crisis and its effects in both the Eurozone and France itself dogged the conservative government of Nicolas Sarkozy, who lost reelection in 2012 against Socialist Francois Hollande.

In June 2012, Hollande's Socialist Party won an overall majority in the legislative elections, giving it the capability to amend the French Constitution and allowing immediate enactment of the promised reforms.