Economic history of Portugal

Remains of garum manufacturing plants show a sharp growth of the canning industry in Portugal, mainly on the coast of Algarve, but also in Póvoa de Varzim, Angeiras (Matosinhos), and the estuary of the Sado River, which made it one of the most important centers for canners in Hispania.

Despite a general impression of sustained development, specially during the 10th and 11th centuries when the area witnessed a noticeable demographic expansion, the Gharb al-Andalus also underwent some dramatic episodes such as the great famine of 740 which decimated the Berber colonists of the Douro region.

[23] Between 1325 and 1357, Afonso IV granted public funding to raise a proper commercial fleet and ordered the first maritime explorations, with the help of Genoese sailors under the command of admiral Manuel Pessanha.

Forced to reduce their activities in the Black Sea, the Republic of Genoa had turned to the north African trade of wheat and olive oil (valued also as an energy source), and a search for gold, although they also visited the ports of Bruges (Flanders) and England.

[24] To promote settlement, the Sesmarias law was issued in 1375, expropriating vacant lands and leasing it to unemployed cultivators, without great effect: by the end of the century, Portugal faced food shortages, having to import wheat from north Africa.

Governor of the rich 'Order of Christ' and holding valuable monopolies on resources in the Algarve, he sponsored voyages down the coast of Mauritania, gathering a group of merchants, shipowners, and stakeholders interested in the sea lanes.

[37] The arrival of the Portuguese in Japan in 1543 initiated the Nanban trade period, with the hosts adopting several technologies and cultural practices, such as the arquebus, European-style cuirasses, European ships, Christianity, decorative art, and language.

Instead, President Óscar Fragoso Carmona invited António de Oliveira Salazar to head the Ministry of Finance, and the latter agreed to accept the position provided he would have veto power over all fiscal expenditures.

Salazar and his policy advisers recognized that additional military expenditure needs, as well as increased transfers of official investment to the "overseas provinces", could only be met by a sharp rise in the country's productive capacity.

"[4] The liberalization of the Portuguese economy continued under Salazar's successor, Prime Minister Marcello José das Neves Caetano (1968–74), whose administration abolished industrial licensing requirements for firms in most sectors and in 1972 signed a free trade agreement with the newly enlarged EC.

[4] Notwithstanding the concentration of the means of production in the hands of a small number of family-based financial-industrial groups, Portuguese business culture permitted a surprising upward mobility of university-educated individuals with middle-class backgrounds into professional management careers.

Portuguese economic growth in the period 1960–1973 under the Estado Novo regime (and even with the effects of an expensive war effort in African territories against independence guerrilla groups from 1961 onwards) created an opportunity for real integration with the developed economies of Western Europe.

Other medium-sized family companies specialized in textiles (for instance those located in the city of Covilhã and the northwest), ceramics, porcelain, glass and crystal (like those of Alcobaça, Caldas da Rainha and Marinha Grande), engineered wood (like SONAE near Porto), motorcycle manufacturing (like Casal and FAMEL in the District of Aveiro), canned fish (like those of Algarve and the northwest which included one of the oldest canned fish companies in continuous operation in the world), fishing, food and beverages (alcoholic beverages, from liqueurs like Licor Beirão and Ginjinha, to beer like Sagres, were produced across the entire country, but Port Wine was one of its most reputed and exported alcoholic beverages), tourism (well established in Estoril/Cascais/Sintra (the Portuguese Riviera) and growing as an international attraction in the Algarve since the 1960s) and in agriculture and agribusiness (like the ones scattered around Ribatejo and Alentejo – known as the breadbasket of Portugal, as well as the notorious Cachão Agroindustrial Complex[61] established in Mirandela, Northern Portugal, in 1963) completed the panorama of the national economy by the early 1970s and included export-orienteed foreign direct investment-funded businesses such as an automotive assembly plant founded in 1962 by Citroën which began operations in 1964 in Mangualde and a Leica factory established in 1973 in Vila Nova de Famalicão.

Communists gained increasing influence in the provisorial cabinets led by Vasco Gonçalves and after a failed coup carried by Spínola on 11 March 1975, the government launched the Processo Revolucionário em Curso (Ongoing Revolutionary Process) marked by nationalizations of hundreds of private companies (including virtually all mass media), politically-based firings (saneamentos políticos) and land expropriations.

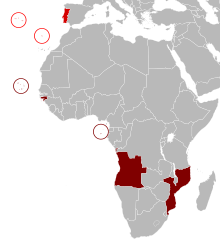

Power in the African colonies was handover to selected former independentist guerrilla movements, which acted as the spark for the appearance of civil wars or the introduction of single party regimes in the newly independent states.

[6][7] Along with the arrival of the retornados, PREC was also marked by political violence and social chaos, exodus of industrialists, a brain drain of technical and managerial experts and sanctioned occupations of agricultural estates, factories and houses.

The 1976 parliamentary and presidential elections allowed Mário Soares to become Prime Minister and General Ramalho Eanes (who played an essential role in defeating the 25 November 1975 coup attempt) to become President of Portugal.

Its Marxist character, which lasted until the 1982 and 1989 revisions, was revealed in a number of its articles, which pointed to a "classless society" and the "socialization of the means of production" and proclaimed all nationalizations made after 25 April 1974, as "irreversible conquests of the working classes".

Although the nationalizations broke up the concentration of economic power that had been held by financial-industrial groups, the subsequent merger of several private firms into single publicly owned enterprises left domestic markets even more monopolized.

Preliminary estimates indicated that part of the observed increase in direct tax revenue in 1989–90 was of a permanent nature, the consequence of a redefinition of taxable income, a reduction in allowed deductions, and the termination of most fiscal benefits for corporations.

[4] The economic dislocations of metropolitan Portugal associated with the income leveling and nationalization-expropriation measures were exacerbated by the sudden loss of the nation's African colonies in 1974 and 1975 and the reabsorption of overseas settlers, the global recession, and the international energy crisis.

[68] The European Union's structural and cohesion funds, and the growth of many of Portugal's main exporting companies, which became leading world players in a number of economic sectors, such as engineered wood, injection molding, plastics, specialized software, ceramics, textiles, footwear, paper, cork, and fine wine, among others, was a major factor in the development of the Portuguese economy and improvements in the standard of living and quality of life.

[69][70] Among the most notable Portugal-based global companies that expanded internationally in the 1990s and 2000s were Sonae, Sonae Indústria, Amorim, Sogrape, EFACEC, Portugal Telecom, Jerónimo Martins, Cimpor, Unicer, Millennium bcp, Salvador Caetano, Lactogal, Sumol + Compal, Cerealis, Frulact, Ambar, Bial, Critical Software, Active Space Technologies, YDreams, Galp Energia, Energias de Portugal, Visabeira, Renova, Delta Cafés, Derovo, Teixeira Duarte, Soares da Costa, Portucel Soporcel, Salsa jeans, Grupo José de Mello, Grupo RAR, Valouro, Sovena Group, Simoldes, Iberomoldes, and Logoplaste.

Greece had been a regular comparison point for Portugal since EU adhesion as both countries were formerly ruled by authoritarian governments and share similar EU-membership history, number of inhabitants, market size and tastes, national economies, Mediterranean culture, sunny weather, and tourist appeal; however, the Greek economic and financial wealth of the first five years of the 21st century was artificially boosted and was hampered by lack of sustainability, and they were caught out by a massive crisis by 2010.

State-funded and supported construction projects such as those related to the Expo 98 World Fair in Lisbon, the 2004 European Football Championship, and a number of new motorways, proved to have little positive effect in fostering sustainable growth.

The short-term impact of these major investments was exhausted by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, and the aim of achieving faster economic growth and the improvement of the population's purchasing power in relation to the EU average did not materialize.

[92] According to a report by the Diário de Notícias[93][failed verification] Portugal had gradually allowed considerable slippage in state-managed public works, as well as inflated top management and head officer bonuses and wages, since the Carnation Revolution in 1974 to the reckoning of an alarming equity and sustainability crisis in 2010.

[95] Portugal requested a €78 billion IMF-EU bailout package, announced by José Sócrates on 3 May 2011, in a bid to stabilise its public finances,[96] as decades-long governmental overspending and an over-bureaucratised civil service was no longer tenable.

[95] After the bailout was announced, the Portuguese government—headed by Pedro Passos Coelho—managed to implement measures to improve the State's financial situation and the country was seen to be moving in the right direction; however, this also led to heavy social costs such as a prominent rise in the unemployment rate to over 15 per cent in the second quarter of 2012.

[98] The unpopular and controversial measures pursued by the Conservative government of Pedro Passos Coelho (some openly exceeding what was requested by the Memorandum of Understanding with the Troika, such as widespread privatisations, flexibilization of labor laws or the elimination of public holidays)[99] made writer and political analyst Miguel Sousa Tavares to coin the term "right-wing PREC" (PREC de direita) in a comparison with the controversial measures taken in 1975 by the Communist-backed government of Vasco Gonçalves which led to a significant fall in the Portuguese economy and standards of living following the 25 de Abril revolution.