Economic history of Iceland

Only in the last twenty years or so have specialist economic historians, educated abroad, entered the field and turned the subject into a distinct discipline.

[3][4] Aðils' lessons were that under Icelandic rule, the nation was prosperous, productive and artistic, but suffered under foreign role.

[3] Historian Guðmundur Hálfdanarson suggests that Aðils himself was doing his best to awaken this slumbering nationalist sentiment and strengthen the Icelandic pursuit of independence.

[5] According to Icelandic historian Axel Kristinsson, there is little historical evidence to substantiate the aforementioned traditional narrative about economic decline after the Saga age.

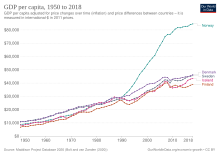

[11][12] According to one assessment by Central Bank of Iceland economists, Post-World War II economic growth has been both significantly higher and more volatile than in other OECD countries.

However, the volatility of growth declined markedly towards the end of the century, which may be attributed to the rising share of the services sector, diversifi cation of exports, more solid economic policies, and increased participation in the global economy.

The other was a wide-ranging social legislation set up to regulate family formations and to maintain a balance between agriculture and the fishing sector in favour of the former.

[15] According to University of Iceland economists Davíd F. Björnsson and Gylfi Zoega, "The policies of the colonial masters in Copenhagen delayed urbanisation.

"[16] A 1998 study found that food consumption patterns differed from those in the rest of Europe: "The prominence of domestically produced dairy products, fish, meat and suet, and the insignificance of cereals until the nineteenth century, are among the most unusual features.

[27] Government interference in the economy increased: "Imports were regulated, trade with foreign currency was monopolized by state-owned banks, and loan capital was largely distributed by state-regulated funds".

"[28] Iceland remained relatively protectionist during the period 1945–1960, despite its participation in the OEEC's Trade Liberalisation Program (TLP).

[30][28] Economic historian Guðmundur Jónsson attributes Icelandic protectionism in the post-WWI period to the "external shock caused by the war, creating an artificial economy internally and the overvaluation of the krona, made adjustment to peacetime circumstances extremely difficult.

Last but not least, Iceland's commercial interests were not easily reconcilable with those of the other members of the OEEC because of her special pattern of trade.

[citation needed] "Nordic Tiger" was a term used to refer to the period of economic prosperity in Iceland that began in the post-Cold-War 1990s.

[36] There are two primary reasons in the academic literature for why Iceland lagged behind: The "Nordic Tiger" period ended in a national financial crisis in 2008, when the country's major banks failed and were taken over by the government.

[citation needed][42] On 28 October 2008, Iceland's central bank raised its interest rate to 18 per cent to fight inflation.

[47][48] The assistance bolstered the Central Bank of Iceland's foreign currency reserves, which was an important first step in the economic recovery.

[49] The IMF did not impose the kind of strict conditions on the assistance as it had done in similar past situations in Asia and Latin America.

According to economists Ásgeir Jónsson and Hersir Sigurjónsson, "Iceland was treated differently from developing countries and former IMF clients.

"[50] Iceland is the only country in the world to have a population under two million yet still have a floating exchange rate and an independent monetary policy.