Economic history of Italy

[4] In Roman times, the Italian Peninsula had a higher population density and economic prosperity than the rest of Europe and the Mediterranean Basin, especially during the 1st and 2nd centuries.

Reasons for their early development are for example the relative military safety of Venetian lagoons, the high population density and the institutional structure which inspired entrepreneurs.

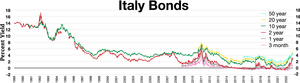

[9] Tradeable bonds as a commonly used type of security, were invented by the Italian city-states (such as Venice and Genoa) of the late medieval and early Renaissance periods.

Wars, political fractionalization, limited fiscal capacity and the shift of world trade to north-western Europe and the Americas were key factors.

Prior to unification, the economy of the many Italian statelets was overwhelmingly agrarian; however, the agricultural surplus produced what historians call a "pre-industrial" transformation in North-western Italy starting from the 1820s,[15] that led to a diffuse, if mostly artisanal, concentration of manufacturing activities, especially in Piedmont-Sardinia under the liberal rule of the Count of Cavour.

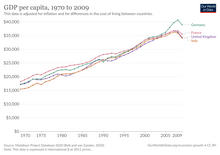

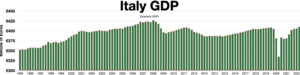

[16] After the birth of the unified Kingdom of Italy in 1861, there was a deep consciousness in the ruling class of the new country's backwardness, given that the per capita GDP expressed in PPS terms was roughly half of that of Britain and about 25% less than that of France and Germany.

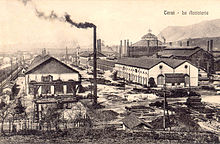

[19] Some large steel and iron works soon clustered around areas of high hydropower potential, notably the Alpine foothills and Umbria in central Italy, while Turin and Milan led a textile, chemical, engineering and banking boom and Genoa captured civil and military shipbuilding.

[23] The Italian diaspora did not affect all regions of the nation equally, principally low income agricultural areas with a high proportion of small peasant land holdings.

[27] For example, the 1887 protectionist reform, instead of safeguarding the arboriculture sectors crushed by 1880s fall in prices, shielded the Po Valley wheat breeding and those Northern textile and manufacturing industries that had survived the liberal years due to state intervention.

[29] The resources necessary to finance the public spending effort were obtained through highly unbalanced land property taxes, which affected the key source of savings available for investment in the growth sectors absent a developed banking system.

[31] This policy destroyed the relationship between the central state and the Southern population by unchaining first a civil war called Brigandage, which brought about 20,000 victims by 1864 and the militarization of the area, and then favouring emigration, especially from 1892 to 1921.

After the rise of Benito Mussolini, the "Iron Prefect" Cesare Mori tried to defeat the already powerful criminal organizations flourishing in the South with some degree of success.

With the invasion of Southern Italy during World War II, the Allies restored the authority of the mafia families, lost during the Fascist period, and used their influence to maintain public order.

[34] The imbalance between North and South was reduced in the 1960s and 1970s through the construction of public works, the implementation of agrarian and scholastic reforms,[35] the expansion of industrialization and the improved living conditions of the population.

To date, the per capita GDP of the South is just 58% of that of the Center-North,[36] but this gap is mitigated by the fact that there the cost of living is around 10–15% lower on average (with even more differences between small towns and big cities) than that in the North of Italy.

[40] However, "once Mussolini acquired a firmer hold of power... laissez-faire was progressively abandoned in favour of government intervention, free trade was replaced by protectionism and economic objectives were increasingly couched in exhortations and military terminology.

This put severe strain on the corporatist model, since the war quickly started going badly for Italy and it became difficult for the government to persuade business leaders to finance what they saw as a military disaster.

After the end of World War II, Italy was in rubble and occupied by foreign armies, a condition that worsened the chronic development gap towards the more advanced European economies.

However, the new geopolitical logic of the Cold War made possible that the former enemy Italy, a hinge-country between Western Europe and the Mediterranean, and now a new, fragile democracy threatened by the NATO occupation forces, the proximity of the Iron Curtain and the presence of a strong Communist party,[48] was considered by the United States as an important ally for the Free World, and received under the Marshall Plan over US$1.2 billion from 1947 to 1951.

[57] The economic recession went on into the mid-1980s until a set of reforms led to the independence of the Bank of Italy[58] and a big reduction of the indexation of wages[59] that strongly reduced inflation rates, from 20.6% in 1980 to 4.7% in 1987.

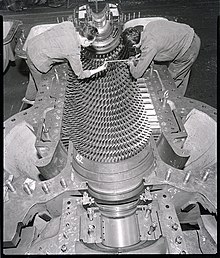

[60] The new macroeconomic and political stability resulted in a second, export-led "economic miracle", based on small and medium-sized enterprises, producing clothing, leather products, shoes, furniture, textiles, jewelry, and machine tools.

As a result of this rapid expansion, in 1987 Italy overtook the UK's economy (an event known as il sorpasso), becoming the fourth richest nation in the world, after the US, Japan and West Germany.

[62] However, the Italian economy of the 1980s presented a problem: it was booming, thanks to increased productivity and surging exports, but unsustainable fiscal deficits drove the growth.

[52] Despite social and political attempts to reduce the difference in wealth between the North and South, and Southern Italy's modernisation, the economic gap remained still pretty wide.

[52] In the 1990s, and still today, Italy's strength was not the big enterprises or corporation, but small to middle-sized family owned businesses and industries, which mainly operated in the North-Western "economic/industrial triangle" (Milan-Turin-Genoa).

Familyism and cronyism are the ultimate causes of the Italian disease.Italy's economy in the 21st century has been mixed, experiencing both relative economic growth and stagnation, recession and stability.

[72] ISTAT predicts that Italy's falling economic growth rate is due to a general decrease in the country's industrial production and exports.

[72] In the period 2014–2019, the economy partially recovered from the disastrous losses incurred during the Great Recession, primarily thanks to strong exports, but nonetheless, growth rates remained well below the Euro area average, meaning that Italy's GDP in 2019 was still 5 per cent below its level in 2008.

[73] Starting from February 2020 after the United States had the first originated from China, Italy was the first country in Europe to be severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic,[74] that eventually expanded to the rest of the world.

Furthermore, the PNRR (Piano Nazionale di Ripresa e Resilienza [it]) had to be re-calibrated and re-agreed with the European Union, to address the new geopolitical situation which led to the energy crisis and damage to supply chains, causing shortages in raw materials.

negative interest rates 2015–2022