Deferent and epicycle

Epicyclical motion is used in the Antikythera mechanism, [citation requested] an ancient Greek astronomical device, for compensating for the elliptical orbit of the Moon, moving faster at perigee and slower at apogee than circular orbits would, using four gears, two of them engaged in an eccentric way that quite closely approximates Kepler's second law.

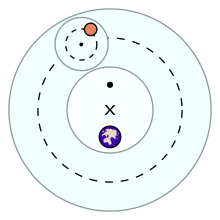

Both circles rotate eastward and are roughly parallel to the plane of the Sun's apparent orbit under those systems (ecliptic).

When ancient astronomers viewed the sky, they saw the Sun, Moon, and stars moving overhead in a regular fashion.

Babylonians did celestial observations, mainly of the Sun and Moon as a means of recalibrating and preserving timekeeping for religious ceremonies.

[4] Other early civilizations such as the Greeks had thinkers like Thales of Miletus, the first to document and predict a solar eclipse (585 BC),[5] or Heraclides Ponticus.

Some Greek astronomers (e.g., Aristarchus of Samos) speculated that the planets (Earth included) orbited the Sun, but the optics (and the specific mathematics – Isaac Newton's law of gravitation for example) necessary to provide data that would convincingly support the heliocentric model did not exist in Ptolemy's time and would not come around for over fifteen hundred years after his time.

Furthermore, Aristotelian physics was not designed with these sorts of calculations in mind, and Aristotle's philosophy regarding the heavens was entirely at odds with the concept of heliocentrism.

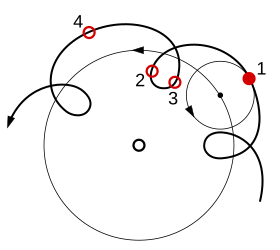

Deferents and epicycles in the ancient models did not represent orbits in the modern sense, but rather a complex set of circular paths whose centers are separated by a specific distance in order to approximate the observed movement of the celestial bodies.

Claudius Ptolemy refined the deferent-and-epicycle concept and introduced the equant as a mechanism that accounts for velocity variations in the motions of the planets.

A heliocentric model is not necessarily more accurate as a system to track and predict the movements of celestial bodies than a geocentric one when considering strictly circular orbits.

It was not until Kepler's proposal of elliptical orbits that such a system became increasingly more accurate than a mere epicyclical geocentric model.

In notes bound with his copy of the Alfonsine Tables, Copernicus commented that "Mars surpasses the numbers by more than two degrees.

The Sun-centered positions displayed a cyclical motion with respect to time but without retrograde loops in the case of the outer planets.

[dubious – discuss] In principle, the heliocentric motion was simpler but with new subtleties due to the yet-to-be-discovered elliptical shape of the orbits.

Mercury orbited closest to the Sun and the rest of the planets fell into place in order outward, arranged in distance by their periods of revolution.

Copernicus' work provided explanations for phenomena like retrograde motion, but really did not prove that the planets actually orbited the Sun.

By treating the Sun and planets as point masses and using Newton's law of universal gravitation, equations of motion were derived that could be solved by various means to compute predictions of planetary orbital velocities and positions.

Analysis of observed perturbations in the orbit of Uranus produced estimates of the suspected planet's position within a degree of where it was found.

[22] According to one school of thought in the history of astronomy, minor imperfections in the original Ptolemaic system were discovered through observations accumulated over time.

Amazed at the difficulty of the project, Alfonso is credited with the remark that had he been present at the Creation he might have given excellent advice.As it turns out, a major difficulty with this epicycles-on-epicycles theory is that historians examining books on Ptolemaic astronomy from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance have found absolutely no trace of multiple epicycles being used for each planet.

According to the historian of science Norwood Russell Hanson: There is no bilaterally-symmetrical, nor eccentrically-periodic curve used in any branch of astrophysics or observational astronomy which could not be smoothly plotted as the resultant motion of a point turning within a constellation of epicycles, finite in number, revolving around a fixed deferent.Any path—periodic or not, closed or open—can be represented with an infinite number of epicycles.

is the imaginary unit, and t is time, correspond to a deferent centered on the origin of the complex plane and revolving with a radius a0 and angular velocity where T is the period.

Finding the coefficients aj to represent a time-dependent path in the complex plane, z = f(t), is the goal of reproducing an orbit with deferent and epicycles, and this is a way of "saving the phenomena" (σώζειν τα φαινόμενα).

[29][30] Pertinent to the Copernican Revolution's debate about "saving the phenomena" versus offering explanations, one can understand why Thomas Aquinas, in the 13th century, wrote: Reason may be employed in two ways to establish a point: firstly, for the purpose of furnishing sufficient proof of some principle [...].

Reason is employed in another way, not as furnishing a sufficient proof of a principle, but as confirming an already established principle, by showing the congruity of its results, as in astronomy the theory of eccentrics and epicycles is considered as established, because thereby the sensible appearances of the heavenly movements can be explained; not, however, as if this proof were sufficient, forasmuch as some other theory might explain them.Being a system that was for the most part used to justify the geocentric model, with the exception of Copernicus' cosmos, the deferent and epicycle model was favored over the heliocentric ideas that Kepler and Galileo proposed.

There is a generally accepted idea that extra epicycles were invented to alleviate the growing errors that the Ptolemaic system noted as measurements became more accurate, particularly for Mars.

[34] Copernicus added an extra epicycle to his planets, but that was only in an effort to eliminate Ptolemy's equant, which he considered a philosophical break away from Aristotle's perfection of the heavens.