Expressionist architecture

The term "Expressionist architecture" initially described the activity of the German, Dutch, Austrian, Czech and Danish avant garde from 1910 until 1930.

Today the meaning has broadened even further to refer to architecture of any date or location that exhibits some of the qualities of the original movement such as; distortion, fragmentation or the communication of violent or overstressed emotion.

Many expressionist architects fought in World War I and their experiences, combined with the political turmoil and social upheaval that followed the German Revolution of 1919, resulted in a utopian outlook and a romantic socialist agenda.

[2] Economic conditions severely limited the number of built commissions between 1914 and the mid-1920s,[3] resulting in many of the most important expressionist works remaining as projects on paper, such as Bruno Taut's Alpine Architecture and Hermann Finsterlin's Formspiels.

Important events in Expressionist architecture include; the Werkbund Exhibition (1914) in Cologne, the completion and theatrical running of the Großes Schauspielhaus, Berlin in 1919, the Glass Chain letters, and the activities of the Amsterdam School.

By 1925, most of the leading architects such as Bruno Taut, Erich Mendelsohn, Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Hans Poelzig, along with other expressionists in the visual arts, had turned toward the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement, a more practical and matter-of-fact approach which rejected the emotional agitation of expressionism.

[5] Until the 1970s scholars (Most notably Nikolaus Pevsner) commonly played down the influence of the expressionists on the later International Style, but this has been re-evaluated in recent years.

Though containing a great variety and differentiation, many points can be found as recurring in works of Expressionist architecture, and are evident in some degree in each of its works: Political, economic and artistic shifts provided a context for the early manifestations of Expressionist architecture; particularly in Germany, where the utopian qualities of Expressionism found strong resonances with a leftist artistic community keen to provide answers to a society in turmoil during and after the events of World War I.

Influence of individualists such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Antoni Gaudí also provided the surrounding context for Expressionist architecture.

[25] The author Franz Kafka in his The Metamorphosis, with its shape shifting matched the material instability of Expressionist architecture[26] Naturalists such as Charles Darwin, and Ernst Haeckel contributed an ideology for the biomorphic form of architects such as Herman Finsterlin.

Poet Paul Scheerbart worked directly with Bruno Taut and his circle, and contributed ideas based on his poetry of glass architecture.

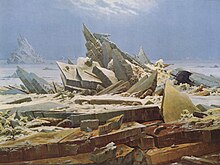

The experience of the sublime was supposed to involve a self-forgetfulness where personal fear is replaced by a sense of well-being and security when confronted with an object exhibiting superior might.

At the beginning of the twentieth century Neo-Kantian German philosopher and theorist of aesthetics Max Dessoir founded the Zeitschift für Ästhetik und allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft, which he edited for many years, and published the work Ästhetik und allgemeine Kunstwissenschaft in which he formulated five primary aesthetic forms: the beautiful, the sublime, the tragic, the ugly, and the comic.

[28] Artistic theories of Wassily Kandinsky, such as Concerning the Spiritual in Art, and Point and Line to Plane were centerpieces of expressionist thinking.

The collaboration of Bruno Taut and the utopian poet Paul Scheerbart attempted to address the problems of German society by a doctrine of glass architecture.

Taut and Scheerbart imagined a society that had freed itself by breaking from past forms and traditions, impelled by an architecture that flooded every building with multicolored light and represented a more promising future.

In the same way as their Arts and Crafts movement predecessors, to expressionist architects, populism, naturalism, and according to Pehnt "Moral and sometimes even irrational arguments were adduced in favor of building in brick".

These were defining moments for the movement, and with its interest in theatres and films, the performing arts held a significant place in expressionist architecture.

[35] Bruno Taut also proposed a film as an anthology for the Glass Chain, entitled Die Galoschen des Glücks(The Galoshes of Fortune) with a name borrowed from Hans Christian Andersen.

The style's regional centres were the larger cities of Northern Germany and the Ruhr area, but the Amsterdam School belongs to the same category.

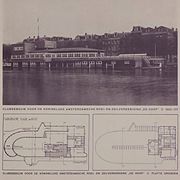

Amsterdam's 1912 cooperative-commercial Scheepvaarthuis (Shipping House) is considered the starting point and prototype for Amsterdam School work: brick construction with complicated masonry, traditional massing, and the integration of an elaborate scheme of building elements (decorative masonry, art glass, wrought-iron work, and exterior figurative sculpture) that embodies and expresses the identity of the building.

In this post war period, a variant of Expressionism, Brutalism, had an honest approach to materials, that in its unadorned use of concrete was similar to the use of brick by the Amsterdam School.

His TWA Terminal at JFK International Airport has an organic form, as close to Herman Finsterlin's Formspiels as any other, save Jørn Utzon's Sydney Opera House.

Expressionistic architecture today is an evident influence in Deconstructivism, the work of Santiago Calatrava, and the organic movement of Blobitecture.

The style is very much influenced by the form and geometry of the natural world and is characterised by the use of analogy and metaphor as the primary inspiration and directive for design.

Basil Al Bayati whose designs have been inspired by trees and plants, snails, whales, insects, dervishes and even myth and literature.