Finnish language

The most widely held view is that they originated as a Proto-Uralic language somewhere in the boreal forest belt around the Ural Mountains region and/or the bend of the middle Volga.

The strong case for Proto-Uralic is supported by common vocabulary with regularities in sound correspondences, as well as by the fact that the Uralic languages have many similarities in structure and grammar.

After the establishment of the Grand Duchy of Finland, and against the backdrop of the Fennoman movement, the language obtained its official status in the Finnish Diet of 1863.

[21][22] However, concerns have been expressed about the future status of Finnish in Sweden, for example, where reports produced for the Swedish government during 2017 show that minority language policies are not being respected, particularly for the 7% of Finns settled in the country.

There were even efforts to reduce the use of Finnish through parish clerk schools, the use of Swedish in church, and by having Swedish-speaking servants and maids move to Finnish-speaking areas.

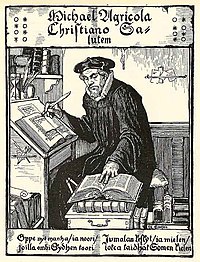

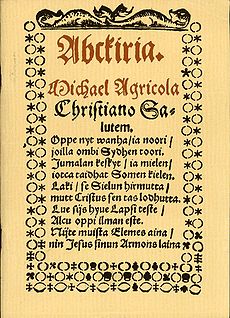

Agricola's ultimate plan was to translate the Bible,[32] but first he had to develop an orthography for the language, which he based on Swedish, German, and Latin.

[33] Though Agricola's intention was that each phoneme (and allophone under qualitative consonant gradation) should correspond to one letter, he failed to achieve this goal in various respects.

The sounds [ð] and [θ(ː)] disappeared from the language, surviving only in a small rural region in Western Finland.

The first known written account in Helsinki slang is from the 1890 short story Hellaassa by young Santeri Ivalo (words that do not exist in, or deviate from, the standard spoken Finnish of its time are in bold): Kun minä eilen illalla palasin labbiksesta, tapasin Aasiksen kohdalla Supiksen, ja niin me laskeusimme tänne Espikselle, jossa oli mahoton hyvä piikis.

Mutta me mentiin Studikselle suoraan Hudista tapaamaan, ja jäimme sinne pariksi tunniksi, kunnes ajoimme Kaisikseen.

[48] The spoken language, on the other hand, is the main variety of Finnish used in popular TV and radio shows and at workplaces, and may be preferred to a dialect in personal communication.

The colloquial language has mostly developed naturally from earlier forms of Finnish, and spread from the main cultural and political centres.

The colloquial language develops significantly faster, and the grammatical and phonological changes also include the most common pronouns and suffixes, which amount to frequent but modest differences.

The literary language certainly still exerts a considerable influence upon the spoken word, because illiteracy is nonexistent and many Finns are avid readers.

A prominent example of the effect of the standard language is the development of the consonant gradation form /ts : ts/ as in metsä : metsän, as this pattern was originally (1940) found natively only in the dialects of the southern Karelian isthmus and Ingria.

The phoneme inventory of Finnish is moderately small,[51] with a great number of vocalic segments and a restricted set of consonant types, both of which can be long or short.

Homosyllabic consonant clusters are mostly absent from native Finnish words, except for a small set of two-consonant sequences in syllable codas, e.g. ⟨rs⟩ in karsta.

However, as many recently adopted loanwords contain clusters, e.g. strutsi from Swedish struts, ('ostrich'), they have been integrated to the modern language in varying degrees.

Characteristic features of Finnish (common to some other Uralic languages) are vowel harmony and an agglutinative morphology; owing to the extensive use of the latter, words can be quite long.

This is a deviation from the phonetic principle, and as such is liable to cause confusion, but the damage is minimal as the transcribed words are foreign in any case.

As an example, take the word kirja "a book", from which one can form derivatives kirjain 'a letter' (of the alphabet), kirje 'a piece of correspondence, a letter', kirjasto 'a library', kirjailija 'an author', kirjallisuus 'literature', kirjoittaa 'to write', kirjoittaja 'a writer', kirjuri 'a scribe, a clerk', kirjallinen 'in written form', kirjata 'to write down, register, record', kirjasin 'a font', and many others.

laiva 'a ship' → laivasto 'navy, fleet' vatkata 'to whisk' → vatkain 'a whisk, mixer' laiva 'a ship' → laivuri 'shipper, shipmaster' tehdä 'to do' → teos 'a piece of work' koti 'home' → koditon 'homeless' neuvo 'advice' → neuvokas 'resourceful' johtaa 'to lead' → johtava 'leading' kauppa 'a shop, commerce' → kaupallinen 'commercial' pappi 'a priest' → pappila 'a parsonage' Venäjä 'Russia' → venäläinen 'Russian person or thing'.

Verbal derivational suffixes are extremely diverse; several frequentatives and momentanes differentiating causative, volitional-unpredictable and anticausative are found, often combined with each other, often denoting indirection.

[citation needed] Words included in this group are e.g. jänis (hare), musta (black), saari (island), suo (swamp) and niemi (cape (geography)).

[59] Often quoted loan examples are kuningas 'king' and ruhtinas 'sovereign prince, high ranking nobleman' from Germanic *kuningaz and *druhtinaz—they display a remarkable tendency towards phonological conservation within the language.

Examples of the ancient Iranian loans are vasara 'hammer' from Avestan vadžra, vajra and orja 'slave' from arya, airya 'man' (the latter probably via similar circumstances as slave from Slav in many European languages[60]).

Notably, a few religious words such as Raamattu ('Bible') are borrowed from Old East Slavic, which indicates language contact preceding the Swedish era.

Unlike previous geographical borrowing, the influence of English is largely cultural and reaches Finland by many routes, including international business, music, film and TV (foreign films and programmes, excluding ones intended for a very young audience, are shown subtitled), literature, and the Web – the latter is now probably the most important source of all non-face-to-face exposure to English.

Some modern terms have been synthesised rather than borrowed, for example: Neologisms are actively generated by the Language Planning Office and the media.

Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: Excerpt from Väinö Linna's Tuntematon sotilas (The Unknown Soldier); these words were also inscribed in the 20 mark note.