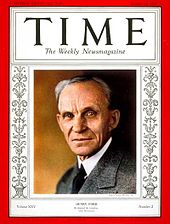

Henry Ford

His commitment to systematically lowering costs resulted in many technical and business innovations, including a franchise system, which allowed for car dealerships throughout North America and in major cities on six continents.

Ford went to work designing an inexpensive automobile, and the duo leased a factory and contracted with a machine shop owned by John and Horace E. Dodge to supply over $160,000 in parts.

It was so inexpensive at $825 in 1908 ($27,980 today), with the price falling every year, that by the 1920s, a majority of American drivers had learned to drive on the Model T.[20][21] Ford created a huge publicity machine in Detroit to ensure every newspaper carried stories and ads about the new product.

As independent dealers, the franchises grew rich and publicized not just the Ford but also the concept of automobiling; local motor clubs sprang up to help new drivers and encourage them to explore the countryside.

Although Ford is often credited with the idea, contemporary sources indicate that the concept and development came from employees Clarence Avery, Peter E. Martin, Charles E. Sorensen, and C. Harold Wills.

[27] Despite this acquisition of a premium car maker, Henry displayed relatively little enthusiasm for luxury automobiles in contrast to Edsel, who actively sought to expand Ford into the upscale market.

Although Henry Ford was against replacing the Model T, now 16 years old, Chevrolet was mounting a bold new challenge as GM's entry-level division in the company's price ladder.

[30] In addition to its price ladder, GM also quickly established itself at the forefront of automotive styling under Harley Earl's Arts & Color Department, another area of automobile design that Henry Ford did not entirely appreciate or understand.

Subsequently, the Ford company adopted an annual model change system similar to that recently pioneered by its competitor General Motors (and still in use by automakers today).

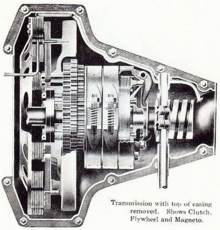

The flathead V8, variants of which were used in Ford vehicles for 20 years, was the result of a secret project launched in 1930 and Henry had initially considered a radical X-8 engine before agreeing to a conventional design.

[28] Ford was a pioneer of "welfare capitalism", designed to improve the lot of his workers and especially to reduce the heavy turnover that had many departments hiring 300 men per year to fill 100 slots.

[36] The move proved extremely profitable; instead of constant employee turnover, the best mechanics in Detroit flocked to Ford, bringing their human capital and expertise, raising productivity, and lowering training costs.

[43] Real profit-sharing was offered to employees who had worked at the company for six months or more, and, importantly, conducted their lives in a manner of which Ford's "Social Department" approved.

[citation needed] In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Edsel—who was president of the company—thought Ford had to come to a collective bargaining agreement with the unions because the violence, work disruptions, and bitter stalemates could not go on forever.

[60] According to biographer Steven Watts, Ford's status as a leading industrialist gave him a worldview that warfare was wasteful folly that retarded long-term economic growth.

[13]: 95–100, 119 [62] In 1918, with the war on and the League of Nations a growing issue in global politics, President Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, encouraged Ford to run for a Michigan seat in the U.S. Senate.

[82] A year and a half later, Ford began publishing a series of articles in the paper under his own name, claiming a vast Jewish conspiracy was affecting America.

Ford later bound the articles into four volumes entitled The International Jew: The World's Foremost Problem, which was translated into multiple languages and distributed widely across the US and Europe.

"[86] In Germany, Ford's The International Jew, the World's Foremost Problem was published by Theodor Fritsch, founder of several antisemitic parties and a member of the Reichstag, influencing German anti-Semitic discourse.

Adolf Hitler wrote, "only Ford, [who], to [the Jews'] fury, still maintains full independence ... [from] the controlling masters of the producers in a nation of one hundred and twenty millions."

[51] A libel lawsuit was brought by San Francisco lawyer and Jewish farm cooperative organizer Aaron Sapiro in response to the antisemitic remarks, and led Ford to close the Independent in December 1927.

[100] Investigative journalist Max Wallace noted that "whatever credibility this absurd claim may have had was soon undermined when James M. Miller, a former Dearborn Independent employee, swore under oath that Ford had told him he intended to expose Sapiro.

[51] Up until the apology, a considerable number of dealers, who had been required to make sure that buyers of Ford cars received the Independent, bought up and destroyed copies of the newspaper rather than alienate customers.

[89][106] James D. Mooney, vice president of overseas operations for General Motors, received a similar medal, the Merit Cross of the German Eagle, First Class.

[89][107] On January 7, 1942, Ford wrote another letter to Sigmund Livingston disclaiming direct or indirect support of "any agitation which would promote antagonism toward my Jewish fellow citizens".

The first plants in Germany were built in the 1920s with the encouragement of Herbert Hoover and the Commerce Department, which agreed with Ford's theory that international trade was essential to world peace and reduced the chance of war.

Both supporters and critics insisted that Fordism epitomized American capitalist development, and that the auto industry was the key to understanding economic and social relations in the United States.

In My Life and Work, Ford predicted that if greed, racism, and short-sightedness could be overcome, then economic and technological development throughout the world would progress to the point that international trade would no longer be based on (what today would be called) colonial or neocolonial models and would truly benefit all peoples.

By this point, Ford, nearing 80, had experienced several cardiovascular events (variously cited as heart attacks or strokes) and was mentally inconsistent, suspicious, and generally no longer fit for such immense responsibilities.

[129] Ford published an anti-smoking book, circulated to youth in 1914, called The Case Against the Little White Slaver, which documented many dangers of cigarette smoking attested to by many researchers and luminaries.