Florentine Renaissance art

[7][8] During the 1430s, Cosimo de' Medici began to take political action, bringing in men he trusted, while he remained in the second line, but the confrontation with Florence's other powerful families, such as the Albizzi and the Strozzi backfired on him and he was forced into exile.

His proclamations from the pulpit of San Marco had a profound influence on Florentine society, which, fearful of the political crisis sweeping the Italian peninsula, turned to a more austere, fundamentalist religion, in contrast to the humanist ideals inspired by the classical world which had run through the preceding period.

[20] The main characteristics of the new style are found in a formulation of the rules of perspective used to organise space, in the attention paid to the human being as an individual, concerning anatomy and physiognomy as well as the representation of emotions, and in the rejection of decorative elements with a concentration on the essential.

In unison with the mentality of Renaissance man, perspective allows the rational use of space according to criteria established by the artist; the choices that determine the rules are subjective, such as vanishing point, distance from the viewer and height of the horizon.

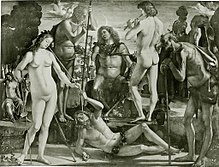

The triangle formed by the spread legs in "compass-style", the ovals of the shield and breastplate, the slight lateral deviation of the head in the opposite direction to that of the body, the detail of the neck tendons, the frowning eyebrows and the contrast of the deep eyes.

The clarity of his architecture is a function of a precise harmonic union of the various parts of the building, which does not come from geometric forms, but emerges from the simple and intuitive repetition of the basic measure, often the Florentine fathom, whose multiples and submultiples generate all the useful dimensions.

[51] Masolino's style moved away from the late Gothic of his earlier works, such as his Madonna of Humility, while Masaccio was already developing a mode of painting that created solid figures with shadow effects reminiscent of sculptures coherently placed in the pictorial space.

An early example, commissioned by Piero di Cosimo de' Medici, is the tondo of the Adoration of the Magi (1438–1441), in which he adds space and volume to the elegance and sanctity of the International Gothic style, unifying the view from the small details in the foreground to the landscape in the background.

The dominant element of the painting, however, is the play of light falling from above, defining the volumes of the figures and architecture, and minimising linear suggestions: the profile of Saint Lucy, for example, stands out smoothly from the contour line thanks to the contrast of the glow against the green background.

The upper part of the cycle contains the Deposition, the Crucifixion and the Resurrection, which, despite their poor state of preservation, highlight episodes with a highly expressive atmosphere, going against the common image spread by Vasari "of an artist incapable of tenderness who, through his dark chromaticism, rendered the works rather raw and harsh".

Alberti seeks to integrate the old with the new, continuing the inlaid decoration in bichromatic marble and leaving the small lower arcades, inserting a classical portal in the centre (derived from that of the Pantheon), with pillar-column motifs on the sides.

[93] Even for the tempietto del Santo Sepolcro, Giovanni Rucellai's funeral monument, Alberti used the white and green marble marquetry of the Florentine Romanesque tradition, creating a classical structure whose dimensions are derived from the golden ratio.

The master's journey began in the workshop, where apprentices entered at a very young age, between thirteen and fifteen, in practical contact with the basics of the trade, starting with the humblest tasks such as cleaning and tidying tools, then progressively taking part in the creation and realisation of works.

[100] The figurative production and dissemination of the ideas of the Accademia Neoplatonica, thanks in particular to the writings of Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino and Pico della Mirandola, gave rise, among the various doctrines, to those linked to the pursuit of harmony and beauty as a means of accessing higher forms of human or divine love, and happiness.

[108] Already in his first dated work, Fortitude (1470), he demonstrates his dexterity in the refined use of colour and chiaroscuro derived from his first master, Filippo Lippi, but animated by a greater solidity and monumentality, in the manner of Verrocchio, with a linear tension learned from Antonio del Pollaiuolo.

[99] In the latter work, the artist's style is already rapidly maturing towards a greater fusion between the elements of the image, with more sensitive and fluid passages of light and chiaroscuro; indeed, the Virgin emerges from a room in semi-darkness, in contrast to a distant, fantastic landscape that appears through two windows in the background.

His audience was not to be found in Neoplatonist intellectual circles, but among the upper-middle class, more accustomed to trade and banking than to ancient literature and philosophy, eager to see themselves portrayed as participating in sacred stories, and little inclined to the frivolities and anxieties that ran through the minds of painters like Botticelli and Filippino Lippi.

In a monumental loggia, an evil judge sits on the throne advised by Ignorance and Suspicion; in front of him is Rancour, the ragged man holding Slander by the arm, a beautiful, richly dressed woman being groomed by Seduction and Deceit.

Examples of stylistic regression are the Altarpiece of San Marco (1488–1490), with its archaic gilded background, and The Mystical Nativity (1501), where spatial distances become confused, proportions are dictated by chosen hierarchies and the expressive poses, often accentuated, end up appearing unnatural.

[127] The last period of the Florentine Republic, during which Piero Soderini held the post of gonaloniere for life, although politically insignificant, marked an astonishing revival in artistic production, favouring a resumption of both public and private commissions.

From the preparatory drawings, we can see the marked difference in representation compared to the earlier battle paintings, organised by Leonardo as a staggering whirlwind with an unprecedented wealth of movement and attitudes linked to "bestial madness" (pazzia bestialissima, as the artist called it).

The consuls of the Arte della Lana and the workers of the Duomo of Florence entrusted him with an enormous block of marble to sculpt a David, an exhilarating challenge on which the artist worked throughout 1503, completing the finishing touches in early 1504.

His last work from the Florentine period of 1507–1508 is the Madonna of the Baldacchino, a large altarpiece with a sacra conversazione organised around the central point constituted by the Virgin's throne, with a grandiose architectonic background cut into the sides to amplify its monumentality.

In architecture, Giuliano[147] and Antonio da Sangallo the Elder excelled in centrally planned religious buildings,[148] while in private construction Baccio d'Agnolo imported classical "Roman-style" models, as in the Palazzo Bartolini Salimbeni.

Initially influenced by his master Cosimo Rosselli and the entourage of Domenico Ghirlandaio, he moved towards a severe, essential conception of sacred images, opening himself up to the suggestions of the "greats", in particular Raphael, with whom he had made friends during his Florentine stay.

The modernity of his language, narrative style and well-ordered rhythms soon made him a point of reference for a group of contemporary artists such as Franciabigio, Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, who in the 1510s formed a school known as scuola dell'Annunziata, antagonistic to that of Fra Bartolomeo and Mariotto Albertinelli in San Marco, with its more solemn, calm stylistic accents.

[150] Andrea del Sarto knew how to reconcile the chiaroscuro of Leonardo, the plasticity of Michelangelo and the classicism of Raphael, thanks to an impeccable execution, free and supple in its modelling, which earned him the appellation of pittore senza errori ('painter without error').

[151] In Florence, he gradually turned to revising old designs, entrusting their execution to his workshop, with the exception of a few works such as the Madonna in Glory with Four Saints (1530) in the Palatine Gallery at Palazzo Pitti, whose characteristics anticipate the devotional motifs of the second half of the century.

[157][158] Of the designs submitted by artists such as Giuliano da Sangallo, Raphael, and Jacopo and Andrea Sansovino, the Pope finally chose Michelangelo's, characterised by a rectangular profile that differed from the "gabled" shape of the basilica's naves.

[158] He created the statues of the two dukes in classical style, showing little interest in achieving accurate likenesses, and the four Allegories of Time, elongated figures of Night, Day, Dusk and Dawn, complementary in theme and pose, as well as the Medici Madonna.