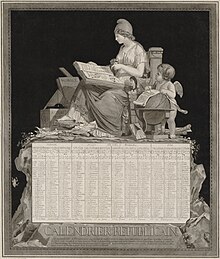

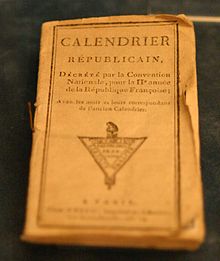

French Republican calendar

[1] The calendar consisted of twelve 30-day months, each divided into three 10-day cycles similar to weeks, plus five or six intercalary days at the end to fill out the balance of a solar year.

It was used in government records in France and other areas under French rule, including Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Malta, and Italy.

The National Constituent Assembly at first intended to create a new calendar marking the "era of Liberty", beginning on 14 July 1789, the date of the Storming of the Bastille.

However, on 2 January 1792 its successor the Legislative Assembly decided that Year IV of Liberty had begun the day before.

The prominent atheist essayist and philosopher Sylvain Maréchal published the first edition of his Almanach des Honnêtes-gens (Almanac of Honest People) in 1788.

[3] The days of the French Revolution and Republic saw many efforts to sweep away various trappings of the Ancien Régime (the old feudal monarchy); some of these were more successful than others.

Amid nostalgia for the ancient Roman Republic, the theories of the Age of Enlightenment were at their peak, and the devisers of the new systems looked to nature for their inspiration.

Natural constants, multiples of ten, and Latin as well as Ancient Greek derivations formed the fundamental blocks from which the new systems were built.

The new calendar was created by a commission under the direction of the politician Gilbert Romme seconded by Claude Joseph Ferry [fr] and Charles-François Dupuis.

They associated with their work the chemist Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau, the mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange, the astronomer Jérôme Lalande, the mathematician Gaspard Monge, the astronomer and naval geographer Alexandre Guy Pingré, and the poet, actor and playwright Fabre d'Églantine, who invented the names of the months, with the help of André Thouin, gardener at the Jardin des plantes of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris.

There was initially a debate as to whether the calendar should celebrate the Great Revolution, which began in July 1789, or the Republic, which was established in 1792.

It was, however, used again briefly in the Journal officiel for some dates during a short period of the Paris Commune, 6–23 May 1871 (16 Floréal–3 Prairial Year LXXIX).

This arrangement was an almost exact copy of the calendar used by the Ancient Egyptians, though in their case the year did not begin and end on the autumnal equinox.

The name "Olympique" was originally proposed[8] but changed to Franciade to commemorate the fact that it had taken the revolution four years to establish a republican government in France.

[10] The numbering of years in the Republican Calendar by Roman numerals ran counter to this general decimalisation tendency.

The Republican calendar year began the day the autumnal equinox occurred in Paris, and had twelve months of 30 days each, which were given new names based on nature, principally having to do with the prevailing weather in and around Paris and sometimes evoking the Medieval Labours of the Months.

[11] In Britain, a contemporary wit mocked the Republican Calendar by calling the months: Wheezy, Sneezy, and Freezy; Slippy, Drippy, and Nippy; Showery, Flowery, and Bowery; Hoppy, Croppy, and Poppy.

[12][13] The historian Thomas Carlyle suggested somewhat more serious English names in his 1837 work The French Revolution: A History,[11] namely Vintagearious, Fogarious, Frostarious, Snowous, Rainous, Windous, Buddal, Floweral, Meadowal, Reapidor, Heatidor, and Fruitidor.

Décades were abandoned at the changeover from Germinal to Floréal year X (20 to 21 April 1802), after Napoleon's Concordat with the Pope.

The priests assigned the commemoration of a so-called saint to each day of the year: this catalogue exhibited neither utility nor method; it was a collection of lies, of deceit or of charlatanism.

We thought that the nation, after having kicked out this canonised mob from its calendar, must replace it with the objects that make up the true riches of the nation, worthy objects not from a cult, but from agriculture – useful products of the soil, the tools that we use to cultivate it, and the domesticated animals, our faithful servants in these works; animals much more precious, without doubt, to the eye of reason, than the beatified skeletons pulled from the catacombs of Rome.

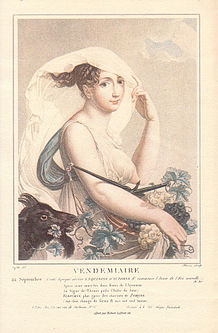

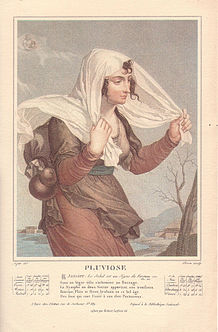

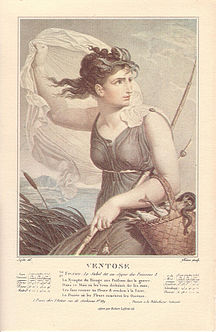

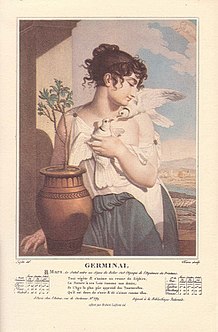

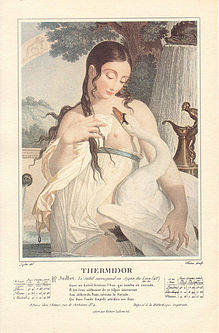

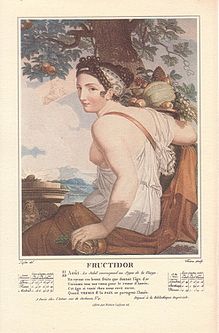

The following pictures, showing twelve allegories for the months, were illustrated by French painter Louis Lafitte (1779–1828), and engraved by Salvatore Tresca [fr] (1750–1815).

A fixed arithmetic rule for determining leap years was proposed by Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre and presented to the Committee of Public Education by Gilbert Romme on 19 Floréal An III (8 May 1795).

The proposal was intended to avoid uncertain future leap years caused by the inaccurate astronomical knowledge of the 1790s (even today, this statement is still valid due to the uncertainty in ΔT).

In particular, the committee noted that the autumnal equinox of year 144 was predicted to occur at 11:59:40 pm local apparent time in Paris, which was closer to midnight than its inherent 3 to 4 minute uncertainty.

The calendar was abolished by an act dated 22 Fructidor an XIII (9 September 1805) and signed by Napoleon, which referred to a report by Michel-Louis-Étienne Regnaud de Saint-Jean d'Angély and Jean Joseph Mounier, listing two fundamental flaws.

The report also noted that the 10-day décade was unpopular and had already been suppressed three years earlier in favor of the seven-day week, removing what was considered by some as one of the calendar's main benefits.

Based on this event, the term "Thermidorian" entered the Marxist vocabulary as referring to revolutionaries who destroy the revolution from the inside and turn against its true aims.