Fundamental interaction

The gravitational interaction is attributed to the curvature of spacetime, described by Einstein's general theory of relativity.

[2] Within the Standard Model, the strong interaction is carried by a particle called the gluon and is responsible for quarks binding together to form hadrons, such as protons and neutrons.

As a residual effect, it creates the nuclear force that binds the latter particles to form atomic nuclei.

The weak interaction is carried by particles called W and Z bosons, and also acts on the nucleus of atoms, mediating radioactive decay.

The electromagnetic force, carried by the photon, creates electric and magnetic fields, which are responsible for the attraction between orbital electrons and atomic nuclei which holds atoms together, as well as chemical bonding and electromagnetic waves, including visible light, and forms the basis for electrical technology.

[3][4] As conventionally interpreted, Newton's theory of motion modelled a central force without a communicating medium.

[7] Conversely, during the 1820s, when explaining magnetism, Michael Faraday inferred a field filling space and transmitting that force.

[8] In 1873, James Clerk Maxwell unified electricity and magnetism as effects of an electromagnetic field whose third consequence was light, travelling at constant speed in vacuum.

The strong interaction, whose force carrier is the gluon, traversing minuscule distance among quarks, is modeled in quantum chromodynamics (QCD).

Predictions are usually made using calculational approximation methods, although such perturbation theory is inadequate to model some experimental observations (for instance bound states and solitons).

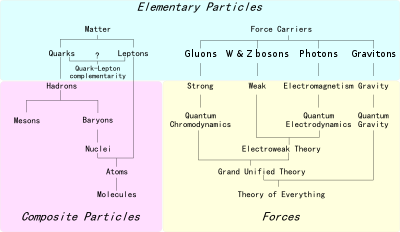

Beyond the Standard Model, some theorists work to unite the electroweak and strong interactions within a Grand Unified Theory[12] (GUT).

Other theorists seek to quantize the gravitational field by the modelling behaviour of its hypothetical force carrier, the graviton and achieve quantum gravity (QG).

Still other theorists seek both QG and GUT within one framework, reducing all four fundamental interactions to a Theory of Everything (ToE).

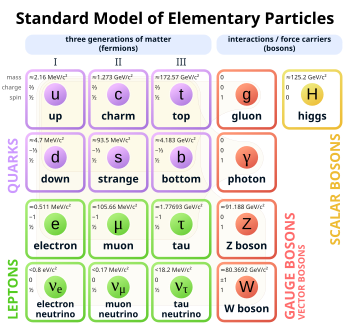

In the conceptual model of fundamental interactions, matter consists of fermions, which carry properties called charges and spin ±1⁄2 (intrinsic angular momentum ±ħ⁄2, where ħ is the reduced Planck constant).

Two cases in point are the unification of: Both magnitude ("relative strength") and "range" of the associated potential, as given in the table, are meaningful only within a rather complex theoretical framework.

The modern (perturbative) quantum mechanical view of the fundamental forces other than gravity is that particles of matter (fermions) do not directly interact with each other, but rather carry a charge, and exchange virtual particles (gauge bosons), which are the interaction carriers or force mediators.

The long range of gravitation makes it responsible for such large-scale phenomena as the structure of galaxies and black holes and, being only attractive, it retards the expansion of the universe.

During the Scientific Revolution, Galileo Galilei experimentally determined that this hypothesis was wrong under certain circumstances—neglecting the friction due to air resistance and buoyancy forces if an atmosphere is present (e.g. the case of a dropped air-filled balloon vs a water-filled balloon), all objects accelerate toward the Earth at the same rate.

For contributions to the unification of the weak and electromagnetic interaction between elementary particles, Abdus Salam, Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979.

The constant speed of light in vacuum (customarily denoted with a lowercase letter c) can be derived from Maxwell's equations, which are consistent with the theory of special relativity.

Albert Einstein's 1905 theory of special relativity, however, which follows from the observation that the speed of light is constant no matter how fast the observer is moving, showed that the theoretical result implied by Maxwell's equations has profound implications far beyond electromagnetism on the very nature of time and space.

In another work that departed from classical electro-magnetism, Einstein also explained the photoelectric effect by utilizing Max Planck's discovery that light was transmitted in 'quanta' of specific energy content based on the frequency, which we now call photons.

The first to hypothesize the gluons of QCD were Moo-Young Han and Yoichiro Nambu, who introduced the quark color charge.

In 1971, Murray Gell-Mann and Harald Fritzsch proposed that the Han/Nambu color gauge field was the correct theory of the short-distance interactions of fractionally charged quarks.

The discovery of asymptotic freedom led most physicists to accept QCD since it became clear that even the long-distance properties of the strong interactions could be consistent with experiment if the quarks are permanently confined: the strong force increases indefinitely with distance, trapping quarks inside the hadrons.

Assuming that quarks are confined, Mikhail Shifman, Arkady Vainshtein and Valentine Zakharov were able to compute the properties of many low-lying hadrons directly from QCD, with only a few extra parameters to describe the vacuum.

QCD is a theory of fractionally charged quarks interacting by means of 8 bosonic particles called gluons.

The weak and electromagnetic forces have already been unified with the electroweak theory of Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg, for which they received the 1979 Nobel Prize in physics.

[22][23][24] Numerous theoretical efforts have been made to systematize the existing four fundamental interactions on the model of electroweak unification.

Another reason to look for new forces is the discovery that the expansion of the universe is accelerating (also known as dark energy), giving rise to a need to explain a nonzero cosmological constant, and possibly to other modifications of general relativity.