Introduction to quantum mechanics

By contrast, classical physics explains matter and energy only on a scale familiar to human experience, including the behavior of astronomical bodies such as the moon.

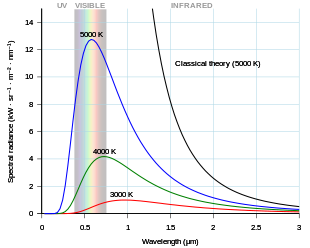

However, towards the end of the 19th century, scientists discovered phenomena in both the large (macro) and the small (micro) worlds that classical physics could not explain.

[1] The desire to resolve inconsistencies between observed phenomena and classical theory led to a revolution in physics, a shift in the original scientific paradigm:[2] the development of quantum mechanics.

Einstein's revolutionary proposal started by reanalyzing Planck's black-body theory, arriving at the same conclusions by using the new "energy quanta".

In 1902, Philipp Lenard directed light from an arc lamp onto freshly cleaned metal plates housed in an evacuated glass tube.

The continuous wave theories of the time predicted that more light intensity would accelerate the same amount of current to higher velocity, contrary to this experiment.

[6]: 23 Einstein then predicted that the electron velocity would increase in direct proportion to the light frequency above a fixed value that depended upon the metal.

[9]: 29 A related concept is Ehrenfest's theorem, which shows that the average values obtained from quantum mechanics (e.g. position and momentum) obey classical laws.

[13] The experiments lead to formulation of its theory described to arise from spin of the electron in 1925, by Samuel Goudsmit and George Uhlenbeck, under the advice of Paul Ehrenfest.

[24] In 1928 Paul Dirac published his relativistic wave equation simultaneously incorporating relativity, predicting anti-matter, and providing a complete theory for the Stern–Gerlach result.

This result came to be called wave-particle duality, one iconic idea along with the uncertainty principle that sets quantum mechanics apart from older models of physics.

If the source intensity is turned down, the same interference pattern will slowly build up, one "count" or particle (e.g. photon or electron) at a time.

It is a fundamental tradeoff inherent in any such related or complementary measurements, but is only really noticeable at the smallest (Planck) scale, near the size of elementary particles.

In the Stern–Gerlach experiment discussed above, the quantum model predicts two possible values of spin for the atom compared to the magnetic axis.

"[39] A year later, Uhlenbeck and Goudsmit identified Pauli's new degree of freedom with the property called spin whose effects were observed in the Stern–Gerlach experiment.

Dirac's equations sometimes yielded a negative value for energy, for which he proposed a novel solution: he posited the existence of an antielectron and a dynamical vacuum.

An early landmark in the study of entanglement was the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox, a thought experiment proposed by Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen which argues that the description of physical reality provided by quantum mechanics is incomplete.

They argued that no action taken on the first particle could instantaneously affect the other, since this would involve information being transmitted faster than light, which is forbidden by the theory of relativity.

[41] In the same year, Erwin Schrödinger used the word "entanglement" and declared: "I would not call that one but rather the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics.

Consequently, the only way that hidden variables could explain the predictions of quantum physics is if they are "nonlocal", which is to say that somehow the two particles are able to interact instantaneously no matter how widely they ever become separated.

[50] Dirac shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1933 with Schrödinger "for the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory".

Initially viewed as a provisional, suspect procedure by some of its originators, renormalization eventually was embraced as an important and self-consistent tool in QED and other fields of physics.

Also, in the late 1940s Feynman diagrams provided a way to make predictions with QED by finding a probability amplitude for each possible way that an interaction could occur.

It is an effect whereby the quantum nature of the electromagnetic field makes the energy levels in an atom or ion deviate slightly from what they would otherwise be.

It was developed in stages throughout the latter half of the 20th century, through the work of many scientists worldwide, with the current formulation being finalized in the mid-1970s upon experimental confirmation of the existence of quarks.

Although the Standard Model is believed to be theoretically self-consistent and has demonstrated success in providing experimental predictions, it leaves some physical phenomena unexplained and so falls short of being a complete theory of fundamental interactions.

The model does not contain any viable dark matter particle that possesses all of the required properties deduced from observational cosmology.

The physical measurements, equations, and predictions pertinent to quantum mechanics are all consistent and hold a very high level of confirmation.

In even a simple light switch, quantum tunneling is absolutely vital, as otherwise the electrons in the electric current could not penetrate the potential barrier made up of a layer of oxide.

[55] Notes are in the main script The following titles, all by working physicists, attempt to communicate quantum theory to laypeople, using a minimum of technical apparatus.