Gaels

James VI and I sought to subdue the Gaels and wipe out their culture;[citation needed] first in the Scottish Highlands via repressive laws such as the Statutes of Iona, and then in Ireland by colonizing Gaelic land with English and Scots-speaking Protestant settlers.

In medieval Ireland, the bardic poets who were the cultural intelligentsia of the nation, limited the use of Gaoidheal specifically to those who claimed genealogical descent from the mythical Goídel Glas.

[22] The ultimate origin of this word is thought to be the Old Irish Ériu, which is from Old Celtic *Iveriu, likely associated with the Proto-Indo-European term *pi-wer- meaning "fertile".

[23] The Érainn, claiming descent from a Milesian eponymous ancestor named Ailill Érann, were the hegemonic power in Ireland before the rise of the descendants of Conn of the Hundred Battles and Mug Nuadat.

[24] Within Ireland itself, the term Éireannach (Irish), only gained its modern political significance as a primary denominator from the 17th century onwards, as in the works of Geoffrey Keating, where a Catholic alliance between the native Gaoidheal and Seanghaill ("old foreigners", of Norman descent) was proposed against the Nuaghail or Sacsanach (the ascendant Protestant New English settlers).

Germanic groups tended to refer to the Gaels as Scottas[30] and so when Anglo-Saxon influence grew at court with Duncan II, the Latin Rex Scottorum began to be used and the realm was known as Scotland; this process and cultural shift was put into full effect under David I, who let the Normans come to power and furthered the Lowland-Highland divide.

(Fine is not to be confused with the term fian, a 'band of roving men whose principal occupations were hunting and war, also a troop of professional fighting-men under a leader; in wider sense a company, number of persons; a warrior (late and rare)'[35]).

[51] With regard to Gaelic genetic genealogy studies, these developments in subclades have aided people in finding their original clan group in the case of a non-paternity event, with Family Tree DNA having the largest such database at present.

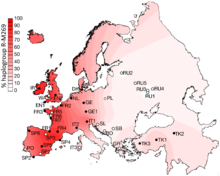

[10] Several genetic traits found at maximum or very high frequencies in the modern populations of Gaelic ancestry were also observed in the Bronze Age period.

However, a large proportion of the Gaelic-speaking population now lives in the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland, and Dublin, Cork as well as Counties Donegal and Galway in Ireland.

[57] According to the U.S. Census in 2000,[3] there are more than 25,000 Irish-speakers in the United States, with the majority found in urban areas with large Irish-American communities such as Boston, New York City and Chicago.

Further to the north, the Érainn's Dál Riata colonised Argyll (eventually founding Alba) and there was a significant Gaelic influence in Northumbria[64] and the MacAngus clan arose to the Pictish kingship by the 8th century.

[66] In their own national epic contained within medieval works such as the Lebor Gabála Érenn, the Gaels trace the origin of their people to an eponymous ancestor named Goídel Glas.

[67] During the Iron Age, there was heightened activity at a number of important royal ceremonial sites, including Tara, Dún Ailinne, Rathcroghan and Emain Macha.

Based on the accounts of Tacitus, some modern historians associate him with an "Irish prince" said to have been entertained by Agricola, Governor of Britain, and speculate at Roman sponsorship.

[70] The Gaels emerged into the clear historical record during the classical era, with ogham inscriptions and quite detailed references in Greco-Roman ethnography (most notably by Ptolemy).

[77] Learned in Greek and Latin during an age of cultural collapse,[78] the Gaelic scholars were able to gain a presence at the court of the Carolingian Frankish Empire; perhaps the best known example is Johannes Scotus Eriugena.

The earliest recorded raids were on Rathlin and Iona in 795; these hit and run attacks continued for some time until the Norsemen began to settle in the 840s at Dublin (setting up a large slave market), Limerick, Waterford and elsewhere.

[81] After a spell when the Norsemen were driven from Dublin by Leinsterman Cerball mac Muirecáin, they returned in the reign of Niall Glúndub, heralding a second Viking period.

At this time, a literary anti-Gaelic sentiment was born and developed by the likes of Gerald of Wales as part of a propaganda campaign (with a Gregorian "reform" gloss) to justify taking Gaelic lands.

The Davidian Revolution saw the Normanisation of Scotland's monarchy, government and church; the founding of burghs, which became mainly English-speaking; and the royally-sponsored immigration of Norman aristocrats.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Gaels were affected by the policies of the Tudors and the Stewarts who sought to anglicise the population and bring both Ireland and the Highlands under stronger centralised control,[84] as part of what would become the British Empire.

The 19th century was the turning point as The Great Hunger in Ireland, and across the Irish Sea the Highland Clearances, caused mass emigration (leading to Anglicisation, but also a large diaspora).

[97] The traditional, or "pagan", worldview of the pre-Christian Gaels of Ireland is typically described as animistic,[98] polytheistic, ancestor venerating and focused on the hero cult of archetypal Gaelic warriors such as Cú Chulainn and Fionn mac Cumhaill.

Unlike other religions, there is no overall "holy book" systematically setting out exact rules to follow, but various works, such as the Lebor Gabála Érenn, Dindsenchas, Táin Bó Cúailnge and Acallam na Senórach, represent the metaphysical orientation of Gaelachas.

The main gods held in high regard were the Tuatha Dé Danann, the superhuman beings said to have ruled Ireland before the coming of the Milesians, known in later times as the aes sídhe.

The Gaels believed that certain heroic persons could gain access to this spiritual realm, as recounted in the various echtra (adventure) and immram (voyage) tales.

[101] At first the Christian Church had difficulty infiltrating Gaelic life: Ireland had never been part of the Roman Empire and was a decentralised tribal society, making patron-based mass conversion problematic.

This balance began to unravel during the 12th century with the polemics of Bernard of Clairvaux, who attacked various Gaelic customs (including polygamy[102] and hereditary clergy) as "pagan".

During the 16th century, with the emergence of Protestantism and Tridentine Catholicism, a distinct Christian sectarianism made its way into Gaelic life, with societal effects carrying on down to this day.