Insular art

[3] The finest period of the style was brought to an end by the disruption to monastic centres and aristocratic life caused by the Viking raids which began in the late 8th century.

[12] C. R. Dodwell, on the other hand, says that in Ireland "the Insular style continued almost unchallenged until the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1170; indeed examples of it occur even as late as the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries".

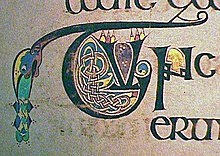

Late Iron Age Celtic art or "Ultimate La Tène", gave the love of spirals, triskeles, circles and other geometric motifs.

[17] Especially in Ireland, the clerical and secular elites were often very closely linked; some Irish abbacies were held for generations among a small kin-group.

Although the first conversion of a Northumbrian king, that of Edwin in 627, was effected by clergy from the Gregorian Mission to Kent, it was the Celtic Christianity of Iona that was initially more influential in Northumbria, founding Lindisfarne on the eastern coast as a satellite in 635.

[22] The majority of examples that survive from the Christian period have been found in archaeological contexts that suggest they were rapidly hidden, lost or abandoned.

[28] Even excepting the existence of workshops in the mid-to-late medieval period, the craftsman may not always have had been responsible for the full design of the works, for example the execution of portions of the Ardagh Chalice evidences a lack of skill compared to the rest of the piece.

[30] The gilt-bronze Rinnegan Crucifixion Plaque (NMI, late 7th or early 8th century) is the best known of a group of nine recorded Irish metal Crucifixion plaques and is comparable in style to figures on many high crosses; it may well have come from a book cover or formed part of a larger altar frontal or high cross.

Only fragments remain from what were probably large pieces of church furniture, probably with metalwork on wooden frameworks, such as shrines, crosses and other items.

These later works, which also including the 11th century River Laune and Clonmacnoise Croziers are heavily influenced by Viking art and have interlace patterns in the Ringerike or Urnes styles.

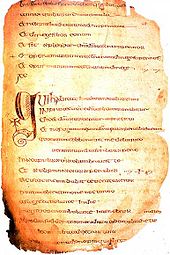

The most fully decorated of all, the Book of Kells, has several mistakes left uncorrected, the text headings necessary to make the Canon tables usable have not been added, and when it was stolen in 1006 for its cover in precious metals, it was taken from the sacristy, not the library.

None of the major Insular manuscripts have preserved their elaborate jewelled metal covers, but we know from documentary evidence that these were as spectacular as the few remaining continental examples.

[37] The re-used metal back cover of the Lindau Gospels (now in the Morgan Library, New York[38]) was made in southern Germany in the late 8th or early 9th century, under heavy Insular influence, and is perhaps the best indication as to the appearance of the original covers of the great Insular manuscripts, although one gold and garnet piece from the Anglo-Saxon Staffordshire Hoard, found in 2009, may be the corner of a book-cover.

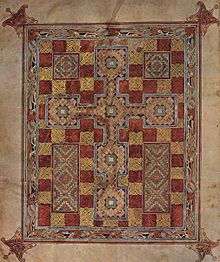

The cloisonné enamel shows Italian influence, and is not found in work from the Insular homelands, but the overall effect is very like a carpet page.

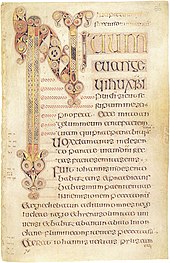

[44] Its date and place of origin remain subjects of debate, with 650–690 and Durrow in Ireland, Iona or Lindisfarne being the normal contenders.

[45] The manuscript is decorated by cross motifs, ribbon interlace, lattice work, carpet pages, and the evangelist symbols.

[46] The figures are highly stylised, and some pages use Germanic interlaced animal ornament, whilst others use the full repertoire of Celtic geometric spirals.

It also contains the earliest historiated initial, a bust probably of Pope Gregory I, which like some other elements of the decoration, clearly derives from a Mediterranean model.

[50] It is also often thought to have been begun in Iona and then continued in Ireland, after disruption from Viking raids; the book survives nearly intact but the decoration is not finished, with some parts in outline only.

Human figures are more numerous than before, though treated in a thoroughly stylised fashion, and closely surrounded, even hemmed in, by decoration as crowded as on the initial pages.

Its beautifully tooled goatskin cover is the oldest Western bookbinding to survive, and a virtually unique example of Insular leatherwork, in an excellent state of preservation.

[56] It appears that, in contrast to later periods, the scribes copying the text were often also the artists of the illuminations, and might include the most senior figures of their monastery.

The 8th-century Cotton Bede shows mixed elements in the decoration, as does the Stockholm Codex Aureus of similar period, probably written in Canterbury.

Many Anglo-Saxon manuscripts written in the south, and later the north, of England show strong Insular influences until the 10th century or beyond, but the pre-dominant stylistic impulse comes from the continent of Europe; carpet-pages are not found, but many large figurative miniatures are.

"Franco-Saxon" is a term for a school of late Carolingian illumination in north-eastern France that used Insular-style decoration, including super-large initials, sometimes in combination with figurative images typical of contemporary French styles.

Even early Anglo-Saxon examples mix vine-scroll decoration of Continental origin with interlace panels, and in later ones the former type becomes the norm, just as in manuscripts.

There is literary evidence for considerable numbers of carved stone crosses across the whole of England, and also straight shafts, often as grave-markers, but most survivals are in the northernmost counties.

[66] The stone monuments erected by the Picts of Scotland north of the Clyde-Forth line between the 6th–8th centuries are particularly striking in design and construction, carved in the typical Easter Ross style related to that of Insular art, though with much less classical influence.

It is also noticeable that these characteristics are always rather more pronounced in the north of Europe than the south; Italian art, even in the Gothic period, always retains a certain classical clarity in form.

These features continue in Ottonian and contemporary French illumination and metalwork, before the Romanesque period further removed classical restraints, especially in manuscripts, and the capitals of columns.