Geology of Ceres

Before the arrival of NASA's Dawn spacecraft in 2015, knowledge of Ceres' geology was limited to spectroscopic studies from Earth-orbital and ground-based telescopes, which tentatively identified the dwarf planet's overall surface composition.

[4] Data from the Dawn mission not only confirmed many of the results of earlier studies, but dramatically increased the understanding of Ceres' composition and evolution,[5] moving it from a largely astronomical object to a geological one.

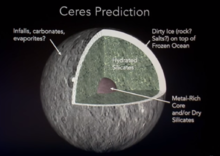

Ceres possesses sufficient gravity to form a rounded, ellipsoid shape, suggesting that it is close to being in hydrostatic equilibrium[6]—one of the conditions for defining a dwarf planet according to the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Ceres' small size means that it cooled much faster than full-sized planets and larger moons, limiting its degree of thermal evolution.

Being the most water-rich body in the inner Solar System after Earth, Ceres is believed to have once hosted a subsurface ocean,[8] the remnant of which may still exist as a global reservoir or as pockets of brines (salty water) at depth.

Ceres orbits the Sun at a mean distance of 2.77 astronomical units (AU), near the center of the asteroid belt.

[9] Ceres is a dark object, having a geometric albedo of 0.094,[10] meaning that on average its surface reflects only 9% of the sunlight striking it.

The composition of the material contributing to the low albedo remains uncertain, but graphitized carbon compounds or the mineral magnetite have been suggested.

Ceres is also sometimes classified as a G-type asteroid,[11][12] which is a subtype of the Tholen C-class and characterized by abundant phyllosilicates, such as clay minerals.

The spacecraft entered orbit around Vesta on July 16, 2011, and completed a 14-month survey mission before leaving for Ceres in late 2012.

Dawn performed near-global geological, chemical, and geophysical mapping of Ceres[8] until its hydrazine fuel was depleted on October 31, 2018.

[5] During the primary mission, the FC mapped nearly the entire surface of Ceres at a spatial resolution of 35 m/pixel in the visible channel and 135 m/pixel in color.

The main science objectives of the FC were to determine Ceres' physical properties, such as rotational state and global shape, to image surface geomorphology, and to produce high-resolution digital terrain models.

[10] Its scientific objective was to determine the mineralogy of surface materials through the diagnostic absorption features of common rock-forming minerals.

[7] The spatial resolution of the spectral images was high enough (100 meters to several kilometers per pixel)[19] to allow associations to be made between mineralogy and surface morphology, linking chemistry with geology.

Comparisons with laboratory spectra indicate that this absorption feature is likely due to the presence of magnesium (Mg)-bearing phyllosilicates such as antigorite (Mg-serpentine) or saponite (Mg-smectite).

[19] Phyllosilicates (see clay minerals) are hydrated silicates produced by aqueous alteration and thus indicative of the presence of liquid water at some point in Ceres’ geological history.

The concentration of water ice, as measured by hydrogen abundance, is highest at Ceres’ polar regions (29 wt.% equivalent H2O) and decreases toward the equator.

[32] Also, some characteristics of its surface and history (such as its distance from the Sun, which weakened solar radiation enough to allow some fairly low-freezing-point components to be incorporated during its formation), point to the presence of volatile materials in the interior of Ceres.

By correlating the presence or absence of central peaks with the sizes of the craters, scientists can infer the properties of Ceres's crust, such as how strong it is.

[citation needed] Several bright surface features were discovered on the dwarf planet Ceres by the Dawn spacecraft in 2015.

Some of these might turn out to be the result of the crust of Ceres shrinking as the heat and other energy accumulated upon formation gradually radiated into space.