Geology of Triton

As a result, Triton's surface geology is largely driven by the dynamics of water ice and other volatiles such as nitrogen and methane.

Triton's geology is vigorous, and has been and continues to be influenced by its unusual history of capture, high internal heat, and its thin but significant atmosphere.

[19] At the time of encounter by the Voyager 2 spacecraft, much of Triton's southern regions was covered by a highly-reflective polar cap of frozen nitrogen which is deposited by its atmosphere.

[17] The eruption of volatiles from Triton's equator and their subsequent migration and deposition to the poles may redistribute enough mass over 10,000 years to cause polar wander.

[22] Triton's southern polar cap is marked by numerous streaks of dark material tracing the direction of prevailing winds.

[26] Though often described as geysers, the driving mechanism of the plumes remain debated and can be broadly divided between exogenic (geyser-like) and endogenic (cryovolcanic) models.

[27] The solar heating model is centered around the observation that the visible geysers were located between 50° and 57°S; at the time of Voyager 2's flyby, Triton was near the peak of its southern summer.

This suggests that solar heating, although very weak at Triton's great distance from the Sun, may play a crucial role in powering the plumes.

It is thought that much of Triton's surface consists of a translucent layer of frozen nitrogen overlying a darker substrate, which could create a kind of "solid greenhouse effect".

As solar radiation penetrates the translucent layer, it warms the darker substrate, sublimating frozen nitrogen into a gas.

The high levels of cryovolcanic activity would lead to a young surface relatively rich in water ice, as well as an eruption rate independent from that of solar seasons at the pole.

This is similar to that which is estimated for Enceladus's cryovolcanic plumes at 200 kg/s (440 lb/s); far greater than Mars' geysers at circa 0.2 kg/s (0.44 lb/s), which are largely agreed to be solar-driven.

The main challenge for the cryovolcanic model is that all of the 120-odd dark streaks thought to be associated with the plumes were found on the southern ice cap.

[27] Bordering Triton's southern polar cap east of Abatos Planum are a sequence of irregularly-shaped dark spots, or maculae, surrounded by a "halo" of bright material.

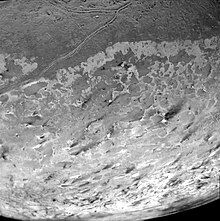

The cantaloupe terrain appears to be dominated by intersecting folds or faults, with ovoid depressions roughly 30–40 km in diameter.

Alternatively, the cratering may be from debris which orbited Neptune, possibly from the disruption of one of its moons; in this case, Triton's average surface age would be younger than 10 million years old.

Cipango Planum is a large, young, smooth cryovolcanic plain that appears to partially cover the older cantaloupe terrain.

These plains are characterized by largely flat floors surrounded by a network of cliffs several hundreds of meters high and crenulated, or irregularly wavy, in profile.

[32] The center of the roughly circular Ruach Planitia appears to have been warped and hosts a central depression—Dilolo Patera—[37] possibly representing a vent whence cryovolcanic material erupted from.