George Armstrong Custer

[4] Following graduation, he worked closely with future Union Army Generals George B. McClellan and Alfred Pleasonton, both of whom recognized his abilities as a cavalry leader.

Custer's division blocked the Southern Army of Northern Virginia's final retreat from their fallen capital city of Richmond in early April 1865 and received the first flag of truce from the exhausted Confederates.

His mythologized status in American history was partly established through the energetic lobbying of his adoring wife Elizabeth Bacon "Libbie" Custer (1842–1933), throughout her long widowhood which spanned six decades longer into the mid-20th century.

[10][citation needed] According to family letters, Custer was named after George Armstrong, a minister, in his devout mother's hope that her son might join the clergy.

[14] In a February 3, 1887, letter to his son's widow Libby, Emanuel related an incident from when George Custer (known as Autie) was about four years old: "He had to have a tooth drawn, and he was very much afraid of blood.

After additional deployments, 2,400 cavalry under McIntosh and 1,200 under Custer remained together with Colonel Alexander Cummings McWhorter Pennington Jr.'s and Captain Alanson Merwin Randol's artillery, who had a total of ten three-inch guns.

Union soldiers were surprised to see Stuart's entire force about a half mile away coming toward them, not in line of battle, but "formed in close column of squadrons... A grander spectacle than their advance has rarely been beheld".

Outnumbered but undaunted, Custer rode to the head of the regiment, "drew his saber, threw off his hat so they could see his long yellow hair" and shouted... "Come on, you Wolverines!

On April 25, after the war officially ended, Custer had his men search for and illegally seize a large, prize racehorse named "Don Juan" near Clarksville, Virginia, worth an estimated $10,000 (several hundred thousand today), along with his written pedigree.

During his entire period of command of the division, Custer encountered considerable friction and near mutiny from the volunteer cavalry regiments who had campaigned along the Gulf coast.

Following the Hancock campaign, Custer was arrested and suspended at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, until August 12, 1868, for being absent without leave (AWOL), after having abandoned his post to see his wife.

At the request of Major General Sheridan, who wanted him for his planned winter campaign against the Cheyenne, he was allowed to return to duty before his one year of suspension had expired and join his regiment on October 7, 1868.

The New York Herald called Grant the "modern Caesar" and asked, "Are officers... to be dragged from railroad trains and ignominiously ordered to stand aside until the whims of the Chief magistrate ... are satisfied?

[70] By the time of Custer's Black Hills expedition in 1874, the level of conflict and tension between the U.S. and many of the Plains Indians tribes (including the Lakota Sioux and the Cheyenne) had become exceedingly high.

The Grant government set a deadline of January 31, 1876, for all Lakota and Arapaho wintering in the "unceded territory" to report to their designated agencies (reservations) or be considered "hostile".

Meanwhile, in the spring and summer of 1876, the Hunkpapa Lakota holy man Sitting Bull had called together the largest gathering of Plains Indians at Ash Creek, Montana (later moved to the Little Bighorn River) to discuss what to do about the whites.

When Crazy Horse and White Bull mounted the charge that broke through the center of Custer's lines, order may have broken down among the soldiers of Calhoun's command,[90] though Myles Keogh's men seem to have fought and died where they stood.

On September 10, 1873, he wrote Libbie, "the Indian battles hindered the collecting, while in that immediate region it was unsafe to go far from the command...."[102] During his service in Kentucky, Custer bought thoroughbred horses.

He says that Joseph White Bull stated he had shot a rider wearing a buckskin jacket and big hat at the riverside when the soldiers first approached the village from the east.

Mo-nah-se-tah was among 53 Cheyenne women and children taken captive by the 7th Cavalry after the Battle of Washita River in 1868, in which Custer commanded an attack on the camp of Chief Black Kettle.

The two women said they shoved their sewing awls into his ears to permit Custer's corpse to "hear better in the afterlife" because he had broken his promise to Stone Forehead never to fight against Native Americans again.

Benteen, who inspected the body, stated that in his opinion the fatal injuries had not been the result of .45 caliber ammunition, which implies the bullet holes had been caused by ranged rifle fire.

"[126] The bodies of Custer and his brother Tom were wrapped in canvas and blankets, then buried in a shallow grave, covered by the basket from a travois held in place by rocks.

Effusive praise from William Eleroy Curtis, the first journalist to report the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, laid the foundation for Custer's status as a tragic hero who furthered the "manifest destiny" of the United States.

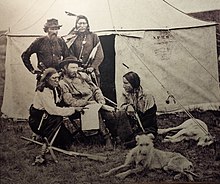

His orderly John Burkman stood guard in front of his tent and on the morning of June 22, 1876, found Custer "hunched over on the cot, just his coat and his boots off, and the pen still in his hand.

[143] General Nelson Miles (who inherited Custer's mantle of famed Indian fighter) and others praised him as a fallen hero betrayed by the incompetence of subordinate officers.

[143] Custer's defenders, however, including historian Charles K. Hofling, have asserted that Gatling guns would have been slow and cumbersome as the troops crossed the rough country between the Yellowstone and the Little Bighorn.

Supporters of Custer claim that splitting the forces was a standard tactic, so as to demoralize the enemy with the appearance of the cavalry in different places all at once, especially when a contingent threatened the line of retreat.

[151] Sharply criticizing the self-styled "Indian fighter", U.S. Indigenous people's organized movements have emphasized Custer's role in the U.S. government's treaty violations and other injustices against Native Americans.

Describing total war methods, Sherman wrote, "We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women, and children...during an assault, the soldiers can not pause to distinguish between male and female, or even discriminate as to age.