Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri

[1] Gemelli Careri realized that he could finance his trip by carefully purchasing goods at each stage that would have enhanced value at the next stage: at Bandar-Abbas on the Persian Gulf, he asserts, the traveler should pick up "dates, wine, spirits, and all the fruits of Persia, which one carries to India either dried or pickled in vinegar, on which one makes a good profit".

After crossing Armenia and Persia, he visited Southern India and entered China, where the Jesuit missionaries assumed that such an unusual Italian visitor could be a spy working for the pope.

In prudence the Chinese should have secured the most dangerous passes: But what I thought most ridiculous was to see the wall run up to the top of a vast high and steep mountain, where the Birds would hardly build much less the Tartar horses climb... And if they conceited those people could make their way climbing the clefts and rocks it was certainly a great folly to believe their Rage could be stopped by so low a wall.

"[3] From Macau, Gemelli Careri sailed to the Philippines, where he stayed two months while waiting for the departure of a Manila galleon, for which he carried quicksilver, for a 300% profit in Mexico.

In the meantime, as Gemelli described it in his journal, the half-year-long transoceanic trip to Acapulco was a nightmare plagued with bad food, epidemic outbursts, and the occasional storm.

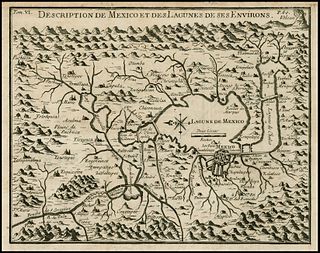

In Mexico, he became friends with the Mexican creole patriot and savant Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, who took the Italian traveler to the great ruins of Teotihuacan.

Later, it was ascertained that he collected important historical documents in order to identify correctly those exotic realities in greater detail.

[15]An 1849 release of The Calcutta Review (a periodical now published by the University of Calcutta), stated the following about Gemelli's writings concerning India: "In a previous number of this Review we made an attempt to describe something of the Court and Camp of the best and wisest prince Muhainmedan India had ever beheld (Aurungzebe, Mogul emperor of Hindustan)... To this we are urged by two main considerations, the character of the age, and the materials at our command.... Sir H. M. Elliot's work has... met with, to a certain extent, adverse criticism, and some doubts have been raised as to the soundness, or the justice, of its conclusions.

Natural productions, the beasts and the birds, manners, Hindu theology, state maxims, the causes of Portuguese supremacy and degradation, anecdotes of the camp, the convent, and the Harem, accidents by water and land, complaints of personal inconvenience, and remarks on the tendency of Eastern despotism, are scattered plentifully throughout a narrative, which owes very much to the author's own liveliness and observation, but occasionally something, we are compelled to say, to the labours of others who had gone before.

"[16] Italian Capuchin friar Ilarione da Bergamo had read Gemelli's account of New Spain when he wrote his travel narrative in the late eighteenth century.