Mikhail Gorbachev

Growing up under the rule of Joseph Stalin in his youth, he operated combine harvesters on a collective farm before joining the Communist Party, which then governed the Soviet Union as a one-party state.

Moving to Stavropol, he worked for the Komsomol youth organization and, after Stalin's death, became a keen proponent of the de-Stalinization reforms of Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev.

Domestically, his policy of glasnost ("openness") allowed for enhanced freedom of speech and press, while his perestroika ("restructuring") sought to decentralize economic decision-making to improve its efficiency.

Growing nationalist sentiment within constituent republics threatened to break up the Soviet Union, leading the hardliners within the Communist Party to launch an unsuccessful coup against Gorbachev in August 1991.

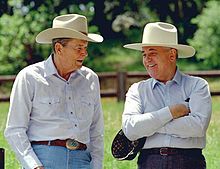

The recipient of a wide range of awards, including the Nobel Peace Prize, in the West he is praised for his role in ending the Cold War, introducing new political and economic freedoms in the Soviet Union, and tolerating both the fall of Marxist–Leninist administrations in eastern and central Europe and the German reunification.

His unsuccessful run for president in 1996 showed, despite neoliberal reforms in Russia at the time, mass unpopularity with the results of his administration and possibly regret for the collapse of the USSR.

[22] He read voraciously, moving from the Western novels of Thomas Mayne Reid to the works of Vissarion Belinsky, Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, and Mikhail Lermontov.

[38] During his studies, an antisemitic campaign spread through the Soviet Union, culminating in the Doctors' plot; Gorbachev publicly defended Volodya Liberman, a Jewish student accused of disloyalty.

[40] One of his first Komsomol assignments in Moscow was to monitor the election polling in Presnensky District to ensure near-total turnout; Gorbachev found that most people voted "out of fear".

[59] In this position, he visited villages in the area and tried to improve the lives of their inhabitants; he established a discussion circle in Gorkaya Balka to help its peasant residents gain social contacts.

[60] Gorbachev and his wife Raisa initially rented a small room in Stavropol,[61] taking daily evening walks around the city and on weekends hiking in the countryside.

[78] In Stavropol, he formed a discussion club for youths,[79] and helped mobilize local young people to take part in Khrushchev's agricultural and development campaigns.

[82] In 1961, Gorbachev played host to the Italian delegation for the World Youth Festival in Moscow;[83] that October, he attended the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

[99] As regional leader, Gorbachev initially attributed economic and other failures to "the inefficiency and incompetence of cadres, flaws in management structure or gaps in legislation", but eventually concluded that they were caused by an excessive centralization of decision making in Moscow.

[100] He began reading translations of restricted texts by Western Marxist authors such as Antonio Gramsci, Louis Aragon, Roger Garaudy, and Giuseppe Boffa, and came under their influence.

[122] As part of the Moscow political elite, Gorbachev and his wife now had access to better medical care and to specialized shops; they were given cooks, servants, bodyguards, and secretaries, many of these spies for the KGB.

[144] Gorbachev continued to cultivate allies both in the Kremlin and beyond,[145] and gave the main speech at a conference on Soviet ideology, where he angered party hardliners by implying that the country required reform.

[147] In June he traveled to Italy as a Soviet representative for the funeral of Italian Communist Party leader Enrico Berlinguer,[148] and in September to Sofia, Bulgaria to attend celebrations of the fortieth anniversary of its liberation from the Nazis by the Red Army.

[151] He felt that the visit helped to erode Andrei Gromyko's dominance of Soviet foreign policy and sent a signal to the United States government that he wanted to improve Soviet–US relations.

[152] On 11 March 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was elected the eighth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union by the Politburo of the CPSU after the death of Konstantin Chernenko.

Growing nationalist sentiment within constituent republics threatened to break up the Soviet Union, leading the hardliners within the Communist Party to launch an unsuccessful coup against Gorbachev in August 1991.

[166] A liberalizer march took place in Moscow criticizing Communist Party rule,[167] while at a Central Committee meeting, the hardliner Vladimir Brovikov accused Gorbachev of reducing the country to "anarchy" and "ruin" and of pursuing Western approval at the expense of the Soviet Union and the Marxist–Leninist cause.

[201] Most G7 members were reluctant, instead offering technical assistance and proposing the Soviets receive "special associate" status—rather than full membership—of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.

[204] Bush visited Moscow in late July, when he and Gorbachev concluded ten years of negotiations by signing the START I treaty, a bilateral agreement on the reduction and limitation of strategic offensive arms.

[278] He never expected to win outright, but thought a centrist bloc could be formed around either himself or one of the other candidates with similar views, such as Grigory Yavlinsky, Svyatoslav Fyodorov, or Alexander Lebed.

[349] US press referred to the presence of "Gorbymania" in Western countries during the late 1980s and early 1990s, as represented by large crowds that turned out to greet his visits,[350] with Time naming him its "Man of the Decade" in the 1980s.

[355] Taubman regarded Gorbachev as being "exceptional ... as a Russian ruler and a world statesman", highlighting that he avoided the "traditional, authoritarian, anti-Western norm" of both predecessors like Brezhnev and successors like Putin.

[215] Gorbachev succeeded in destroying what was left of totalitarianism in the Soviet Union; he brought freedom of speech, of assembly, and of conscience to people who had never known it, except perhaps for a few chaotic months in 1917.

[359] However, he remains a controversial figure in former Soviet-occupied and administered countries such as the Baltic States, Ukraine, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Poland, after violent repressions against the local populations who sought independence.

Locals have stated that they consider western veneration of the man an injustice and have said they do not understand his positive legacy in the west, with a group of Lithuanians having pursued legal action against him.