Halogen bond

[16] The σ-hole concept readily extends to pnictogen, chalcogen and aerogen bonds, corresponding to atoms of Groups 15, 16 and 18 (respectively).

[18] In 1814, Jean-Jacques Colin discovered (to his surprise) that a mixture of dry gaseous ammonia and iodine formed a shiny, metallic-appearing liquid.

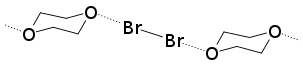

[20] Then, in 1954, Odd Hassel fruitfully applied the distinction to rationalize the X-ray diffraction patterns associated with a mixture of 1,4-dioxane and bromine.

[22] Dumas and coworkers first coined the term "halogen bond" in 1978, during their investigations into complexes of CCl4, CBr4, SiCl4, and SiBr4 with tetrahydrofuran, tetrahydropyran, pyridine, anisole, and di-n-butyl ether in organic solvents.

Through systematic and extensive microwave spectroscopy of gas-phase halogen bond adducts, Legon and coworkers drew attention to the similarities between halogen-bonding and better-known hydrogen-bonding interactions.

[31] Alternatively, the steric sensitivity of halogen bonds can cause bulky molecules to crystallize into porous structures; in one notable case, halogen bonds between iodine and aromatic π-orbitals caused molecules to crystallize into a pattern that was nearly 40% void.

Conjugated polymers offer the tantalizing possibility of organic molecules with a manipulable electronic band structure, but current methods for production have an uncontrolled topology.

Interestingly, oxygen atoms typically do not attract halogens with their lone pairs, but rather the π electrons in the carbonyl or amide group.

For example, inhibitor IDD 594 binds to human aldose reductase through a bromine halogen bond, as shown in the figure.