Hammond's postulate

Hammond's postulate explains this observation by describing how varying the enthalpy of a reaction would also change the structure of the transition state.

By measuring the effects of aromatic substituents and applying Hammond's postulate it was concluded that the rate-determining step involves formation of a transition state that should resemble the intermediate complex.

[6] During the 1940s and 1950s, chemists had trouble explaining why even slight changes in the reactants caused significant differences in the rate and product distributions of a reaction.

In 1955 George Hammond, a young professor at Iowa State University, postulated that transition-state theory could be used to qualitatively explain the observed structure-reactivity relationships.

[8] However, Hammond's version has received more attention since its qualitative nature was easier to understand and employ than Leffler's complex mathematical equations.

Case (c) depicts the potential diagram for an endothermic reaction, in which, according to the postulate, the transition state should more closely resemble that of the intermediate or the product.

Another significance of Hammond’s postulate is that it permits us to discuss the structure of the transition state in terms of the reactants, intermediates, or products.

To understand what is meant by an “early” transition state, the Hammond postulate represents a curve that shows the kinetics of this reaction.

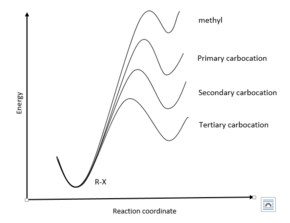

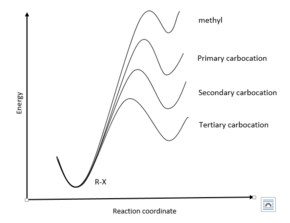

The stabilities of the carbocations formed by this dissociation are known to follow the trend tertiary > secondary > primary > methyl.

[12] Therefore, to interpret this reaction, it is important to look at the transition state, which resembles the concerted rate limiting step.

[13] An E1 reaction consists of a unimolecular elimination, where the rate determining step of the mechanism depends on the removal of a single molecular species.

[14] Furthermore, studies describe a typical kinetic resolution process that starts out with two enantiomers that are energetically equivalent and, in the end, forms two energy-inequivalent intermediates, referred to as diastereomers.

Factors that affect the rate determining step are stereochemistry, leaving groups, and base strength.

A theory, for an E2 reaction, by Joseph Bunnett suggests the lowest pass through the energy barrier between reactants and products is gained by an adjustment between the degrees of Cβ-H and Cα-X rupture at the transition state.

However, Hammond's postulate indirectly gives information about the rate, kinetics, and activation energy of reactions.

Hence, it gives a theoretical basis for the understanding the Bell–Evans–Polanyi principle, which describes the experimental observation that the enthalpy and rate of a similar reactions were usually correlated.

While the rate of a reaction depends just on the activation energy (often represented in organic chemistry as ΔG‡ “delta G double dagger”), the final ratios of products in chemical equilibrium depends only on the standard free-energy change ΔG (“delta G”).

In these kinds of reactions, especially when run at lower temperatures, the reactants simply react before the rearrangements necessary to form a more stable intermediate have time to occur.

At higher temperatures when microscopic reversal is easier, the more stable thermodynamic product is favored because these intermediates have time to rearrange.