Harmonic oscillator

If F is the only force acting on the system, the system is called a simple harmonic oscillator, and it undergoes simple harmonic motion: sinusoidal oscillations about the equilibrium point, with a constant amplitude and a constant frequency (which does not depend on the amplitude).

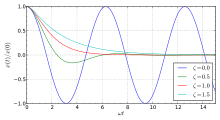

Depending on the friction coefficient, the system can: The boundary solution between an underdamped oscillator and an overdamped oscillator occurs at a particular value of the friction coefficient and is called critically damped.

Mechanical examples include pendulums (with small angles of displacement), masses connected to springs, and acoustical systems.

Other analogous systems include electrical harmonic oscillators such as RLC circuits.

Harmonic oscillators occur widely in nature and are exploited in many manmade devices, such as clocks and radio circuits.

In addition to its amplitude, the motion of a simple harmonic oscillator is characterized by its period

The position at a given time t also depends on the phase φ, which determines the starting point on the sine wave.

where The value of the damping ratio ζ critically determines the behavior of the system.

The amplitude A and phase φ determine the behavior needed to match the initial conditions.

The time an oscillator needs to adapt to changed external conditions is of the order τ = 1/(ζω0).

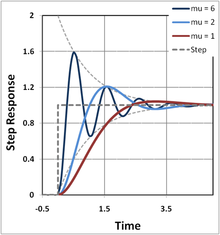

The general solution is a sum of a transient solution that depends on initial conditions, and a steady state that is independent of initial conditions and depends only on the driving amplitude

The steady-state solution is proportional to the driving force with an induced phase change

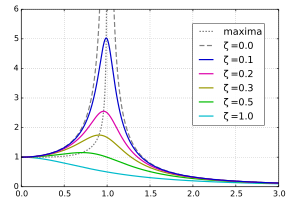

For strongly underdamped systems the value of the amplitude can become quite large near the resonant frequency.

) damped harmonic oscillator and represent the system's response to other events that occurred previously.

Parametric oscillators have been developed as low-noise amplifiers, especially in the radio and microwave frequency range.

Parametric excitation differs from forcing, since the action appears as a time varying modification on a system parameter.

is known as the universal oscillator equation, since all second-order linear oscillatory systems can be reduced to this form.

The solution based on solving the ordinary differential equation is for arbitrary constants c1 and c2

Apply the "complex variables method" by solving the auxiliary equation below and then finding the real part of its solution:

Compare this result with the theory section on resonance, as well as the "magnitude part" of the RLC circuit.

This amplitude function is particularly important in the analysis and understanding of the frequency response of second-order systems.

This phase function is particularly important in the analysis and understanding of the frequency response of second-order systems.

Below is a table showing analogous quantities in four harmonic oscillator systems in mechanics and electronics.

If analogous parameters on the same line in the table are given numerically equal values, the behavior of the oscillators – their output waveform, resonant frequency, damping factor, etc.

The problem of the simple harmonic oscillator occurs frequently in physics, because a mass at equilibrium under the influence of any conservative force, in the limit of small motions, behaves as a simple harmonic oscillator.

The constant term V(x0) is arbitrary and thus may be dropped, and a coordinate transformation allows the form of the simple harmonic oscillator to be retrieved:

Assuming no damping, the differential equation governing a simple pendulum of length

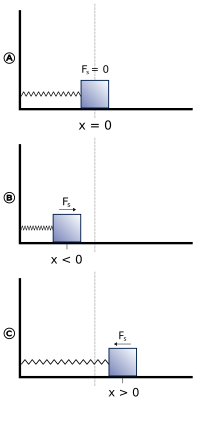

where F is the force, k is the spring constant, and x is the displacement of the mass with respect to the equilibrium position.

The minus sign in the equation indicates that the force exerted by the spring always acts in a direction that is opposite to the displacement (i.e. the force always acts towards the zero position), and so prevents the mass from flying off to infinity.

By using either force balance or an energy method, it can be readily shown that the motion of this system is given by the following differential equation: