Historical criticism

In this process, it is important to understand the intentions, motivations, biases, prejudices, internal consistency, and even the truthfulness of the sources being studied.

Involuntary witnesses that did not intend to transmit a piece of information or present it to an external audience, but end up doing so nonetheless, are considered greatly valuable.

The perspective of the early historical critic was influenced by the rejection of traditional interpretations that came about with the Protestant Reformation.

In this context, an approach called historicism may be applied, where the historical interpretation of cause-and-effect relationships takes place under the framework of methodological naturalism.

This is often a prerequisite for the application of downstream critical methods, as some confidence in what the text originally said is needed before dissecting it for its sources, form, and editorial history.

For example, letters, court archives, hymns, parables, sports reports, wedding announcements, and so forth are recognizable by their use of standardized formulae and stylized phrases.

Many sayings of Jesus have a recognizable formulaic structure, including the Beatitudes and the woe pronouncements upon the Pharisees.

[24] Redaction criticism studies "the collection, arrangement, editing and modification of sources" and is frequently used to reconstruct the community and purposes of the authors of the text.

Instances of redaction may cover "the selection of material, the editorial links, summaries and comments, expansions, additions, and clarifications" on the part of the redactor.

Redaction criticism can become complicated when multiple redactors are involved, especially over the course of time, producing an iteration of stages or recensions of the text.

[30] Another concern expressed by some is that the historical-critical method commits the investigator to a secular worldview, ruling out the possibility of any transcendental truth to the claims of the text being studied.

The second trend emerges from the work of feminist theologians who have argued that historical criticism is not impartial or objective, but instead is a tool for reasserting the hegemony of the interests of Western males.

Second, postcolonial and feminist readings of the Bible are easily integrated as a part of historical criticism, and these can play their role as a corrective of argumentation in the field that has proceeded from ideological influences.

Julius Africanus advanced several critical arguments in a letter to Origen as to why he believed that the story of Susanna in the Book of Daniel was not authentic.

In 1440, Lorenzo Valla demonstrated that the Donation of Constantine was a forgery on the basis of linguistic, legal, historical, and political arguments.

The Protestant Reformation saw an increase in efforts to plainly interpret the text of the Bible without the overriding lenses of tradition.

Approaches in this period saw an attitude that stressed going "back to the sources", collecting manuscripts (whose authenticity was assessed), establishing critical editions of religious texts, the learning of original languages, etc.

John Lightfoot stressed the Jewish background of the New Testament, whose understanding would involve the study of texts included in the rabbinic literature.

After the groundbreaking work on the New Testament by Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), the next generation, which included scholars such as David Friedrich Strauss (1808–1874) and Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–1872), analyzed in the mid-19th century the historical records of the Middle East from biblical times, in search of independent confirmation of events in the Bible.

Such ideas influenced thought in England through the work of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and, in particular, through George Eliot's translations of Strauss's The Life of Jesus (1846) and Feuerbach's The Essence of Christianity (1854).

In 1860, seven liberal Anglican theologians began the process of incorporating this historical criticism into Christian doctrine in Essays and Reviews, causing a five-year storm of controversy, which completely overshadowed the arguments over Charles Darwin's newly published On the Origin of Species.

La Vie de Jésus (1863), the seminal work by a Frenchman, Ernest Renan (1823–1892), continued in the same tradition as Strauss and Feuerbach.

In Catholicism, L'Evangile et l'Eglise (1902), the magnum opus by Alfred Loisy against the Essence of Christianity of Adolf von Harnack[citation needed] (1851–1930) and La Vie de Jesus of Renan, gave birth to the modernist crisis (1902–61).

In 1943, Pope Pius XII issued the encyclical Divino afflante Spiritu, making historical criticism not only permissible but "a duty".

[40] In 1964, the Pontifical Biblical Commission published the Instruction on the Historical Truth of the Gospels, which confirmed the method and delineated how its tools can be used to aid in exegesis.

Due to these trends, Roman Catholic scholars entered into academia and have since made substantial contributions to the field of biblical studies.

The historical-grammatical method of biblical interpretation has been preferred by evangelicals, but is not held by the preponderance of contemporary scholars affiliated to major universities.

[45] Gleason Archer Jr., O. T. Allis, C. S. Lewis,[46] Gerhard Maier, Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Robert L. Thomas, F. David Farnell, William J. Abraham, J. I. Packer, G. K. Beale and Scott W. Hahn rejected the historical-critical hermeneutical method as evangelicals.

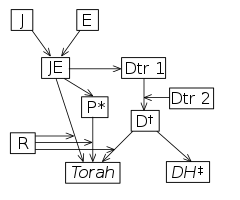

| * | includes most of Leviticus |

| † | includes most of Deuteronomy |

| ‡ | " Deuteronomic history ": Joshua, Judges, 1 & 2 Samuel, 1 & 2 Kings |