Hindustani phonology

This contrast is often not realized by Urdu speakers, and always neutralized in Hindi (where both sounds uniformly correspond to [aː]).

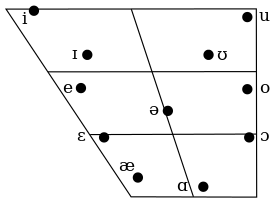

[8] The vowel represented graphically as ऐ – اَے (romanized as ai) has been variously transcribed as [ɛː] or [æː].

Most native consonants may occur geminate (doubled in length; exceptions are /bʱ, ɽ, ɽʱ, ɦ/).

The series of so-called voice aspirates should now properly be considered to involve the voicing mechanism of murmur, in which the air flow passes through an aperture between the arytenoid cartilages, as opposed to passing between the ligamental vocal bands.

[30] In intervocalic position, it may have a single contact and be described as a flap [ɾ],[31] but it may also be a clear trill, especially in word-initial and syllable-final positions, and geminate /rː/ is always a trill in Arabic and Persian loanwords, e.g. zarā [zəɾaː] (ज़रा – ذرا 'little') versus well-trilled zarrā [zəraː] (ज़र्रा – ذرّہ 'particle').

There are murmured sonorants, [lʱ, rʱ, mʱ, nʱ], but these are considered to be consonant clusters with /ɦ/ in the analysis adopted by Ohala (1999).

The dental plosives in Hindustani are laminal denti-alveolar as in Spanish, and the tongue-tip must be well in contact with the back of the upper front teeth.

[32] In some Indo-Aryan languages, the plosives [ɖ, ɖʱ] and the flaps [ɽ, ɽʱ] are allophones in complementary distribution, with the former occurring in initial, geminate and postnasal positions and the latter occurring in intervocalic and final positions.

However, in Standard Hindi they contrast in similar positions, as in nīṛaj (नीड़ज – نیڑج 'bird') vs niḍar (निडर – نڈر 'fearless').

/ʋ/ is pronounced [w] in onglide position, i.e. between an onset consonant and a following vowel, as in pakwān (पकवान پکوان, 'food dish'), and [v] elsewhere, as in vrat (व्रत ورت, 'vow').

[34] In most situations, the allophony is non-conditional[contradictory], i.e. the speaker can choose [v], [w], or an intermediate sound based on personal habit and preference, and still be perfectly intelligible, as long as the meaning is constant.

Being Persian in origin, these are seen as a defining feature of Urdu, although these sounds officially exist in Hindi and modified Devanagari characters are available to represent them.

[35][36] Among these, /f, z/, also found in English and Portuguese loanwords, are now considered well-established in Hindi; indeed, /f/ appears to be encroaching upon and replacing /pʰ/ even in native (non-Persian, non-English, non-Portuguese) Hindi words as well as many other Indian languages such as Bengali, Gujarati and Marathi, as happened in Greek with phi.

[25][35][38] The sibilant /ʃ/ is found in loanwords from all sources (Arabic, English, Portuguese, Persian, Sanskrit) and is well-established.

[39][24] In contrast, for native speakers of Urdu, the maintenance of /f, z, ʃ/ is not commensurate with education and sophistication, but is characteristic of all social levels.

[27][24] Being the main sources from which Hindustani draws its higher, learned terms, English, Sanskrit, Arabic, and to a lesser extent Persian provide loanwords with a rich array of consonant clusters.

[40] Schmidt (2003:293) lists distinctively Sanskrit/Hindi biconsonantal clusters of initial /kr, kʃ, st, sʋ, ʃr, sn, nj/ and final /tʋ, ʃʋ, nj, lj, rʋ, dʒj, rj/, and distinctively Perso-Arabic/Urdu biconsonantal clusters of final /ft, rf, mt, mr, ms, kl, tl, bl, sl, tm, lm, ɦm, ɦr/.