Historic preservation

The idea of preserving sites linked to the Ancien régime and earlier circulated as a result, and under impetus of Talleyrand, the Assembly, on the 13th of October, created the commission des monuments (transl.

[6] The vandalism and widespread destruction which accompanied the French Revolution had inspired several such responses, and the first known register of such buildings was an inventory of the castles begun by Louis XVI by the conseil des bâtiments civils (transl.

During this period, the combination of reluctance to understand the government's prerogatives and the fact that the classification of private property required the owners' consent resulted in the gradual decrease in the number of registered monuments.

In 1866, Lord Brownlow who lived at Ashridge House, tried to enclose the adjoining Berkhamsted Common with 5-foot (2 m) steel fences in an attempt to claim it as part of his estate.

His experience at Tattershall influenced Lord Curzon to push for tougher heritage protection laws in Britain, which saw passage as the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act 1913.

The National Trust was founded in 1894 by Octavia Hill, Sir Robert Hunter, and Hardwicke Canon Rawnsley as the first organisation of its type in the world.

[33][34][35] The British government gave the new charity an £80 million grant to help establish it as an independent trust, although the historic properties remained in the ownership of the state.

It defined that any physical building or space that was at least fifty years old and "which are of general interest because of their beauty, their meaning to science or their social value" and must thus be preserved.

James Marston Fitch also offered guidance and support towards the founding of the Master of Preservation Studies Degree within the Tulane School of Architecture[59] in 1996.

Little came of it until mounting public pressure during the early 20th century from the Ramblers' Association and other groups led to the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949.

[68][69] Melbourne was founded in 1835 and grew enormously in wealth and prosperity following the 1850s gold rush, which resulted in a construction boom: large edifices were erected to serve as public buildings such as libraries, court houses, schools, churches, and offices.

In the years leading up to World War II the Whelan the Wrecker firm had already pulled down thousands of structures in both the city and surrounding suburbs, as Melbourne became particularly conscious of International Modernism.

Sydney (Australia's oldest city) was also affected by the International Modernism period and also suffered an extensive loss of its Victorian architecture, something that subsisted well into the 1980s.

From the 1950s onwards, many of Sydney's handsome sandstone and masonry buildings were wiped away by architects and developers who built "brown concrete monstrosities" in their place.

Not regulated by the Planning Act, the City of Adelaide endeavoured to create on a similar scheme, which became known as the townscape initiative, facilitating one of the most destructive political debates in the council's history.

"Conservation" is taken as the more general term, referring to all actions or processes that are aimed at safeguarding the character-defining elements of a cultural resource so as to retain its heritage value and extend its physical life.

It has been through several changes and amendments specifically regarding preservation,[78] but over the years it hasn't been enforced and many historical sites were destroyed, as the state was prioritizing developmental and economic interests.

[84] Other organizations which have contributed to the efforts of historic preservation are the Macedonian National Committee of ICOMOS and the NI Institute for Protection of Monuments of Culture and Museum-Ohrid.

The institute has since executed numerous efforts for historic preservation, most notably aiding the recognition of the city of Ohrid as a UNESCO site of cultural heritage in 1979.

[86] Today, the main authority for historic preservation is the Cultural Heritage Protection Office (Управа за заштита на културно наследство).

According to Article 1 of the convention, monuments, groups of buildings, and sites "which are of outstanding universal value from the point of view of history, art or science" are to be designated cultural heritage.

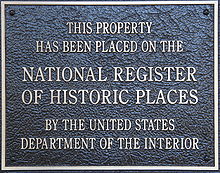

[92][93][94][95] Unique to the United States is the requirement in federal law, stipulated in the amended National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, that all owners of property that would be designated as World Heritage must provide consent to this treatment.

Historic England is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport.

Countermeasures include applying early warning and monitoring technologies and methods, using traditional and modern preventive solutions on site, adequate maintenance with proper skills and disaster preparedness and mitigation measures.

[100] Many historic preservation and cultural resource management scholars, such as Erica Avrami,[101] Sara Bronin,[102] Gail Dubrow,[103] Jamesha Gibson,[104] Ned Kaufman,[105] Thomas King,[106] Michelle Magalong,[107] Kenyatta McLean,[108] Sharon Milholland,[109] Andrea Roberts,[110] and Jeremy Wells,[100] have presented evidence that a significant part of historic preservation practice remains biased toward people who identify as white, male, non-Latino, and who have wealth.

Climate change, especially in relation to sea level rise and associated weather events (e.g., hurricanes) threatens many historic buildings and places.

[120] What both of these movements advocate is a move from positivism and scientism in the practice of identifying, interpreting, and preserving/conserving movable and immovable heritage toward more emancipatory ontological orientations centered in the social sciences.

[124] Many of the concepts inherent in people-centered preservation align with the need to address deficits in diversity, inclusion, equity, and justice in policy and practice.

[125] This was followed by Heritage Protection for the 21st Century, published by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, which continued to refine policy reform arguments in the treatment of the historic environment in the UK.

[131] Historic objects in galleries, museums and archives face the challenge from fine particulates representing an aesthetic issue and an agent of chemical degradation.