History of Northern Epirus from 1913 to 1921

However, Italy and Austria-Hungary opposed this, and the Treaty of Florence in 1913 awarded Northern Epirus to the newly established Principality of Albania, which had a predominantly Muslim population.

Consequently, the Greek army withdrew from the region, but Christian Epirotes rejected the international decision and proceeded to establish, with Greece's tacit support, an autonomous government[note 1] in Argyrókastro (Gjirokastër).

However, a shift in the political leadership in Rome and Greece's military conflicts with Mustafa Kemal's Turkey ultimately benefited Albania, which finally acquired the region on 9 November 1920.

[2] Additionally, a portion of the Albanian-speaking Orthodox population exhibited a pronounced sense of Greek national identity[note 2] and were the initial supporters of the Epirote autonomy movement.

[6] In March 1913, the Greek army, engaged in combat with the Ottoman Empire in the First Balkan War, breached Turkish fortifications in Epirus at the Battle of Bizani.

[8] Following the conclusion of the First Balkan War, the majority of historical Epirus was under Greek control, extending from the Ceraunian Mountains above Himara to Lake Prespa to the east.

[10] However, these two countries sought to exert control over Albania, which, according to Italian Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni, would afford whoever possessed it "undeniable supremacy over the Adriatic."

Greek Prime Minister Elefthérios Venizélos complied with this request, in the hope of gaining favor with the Powers and securing their support in the issue of sovereignty over the North Aegean islands, which were contested by the Ottoman Empire.

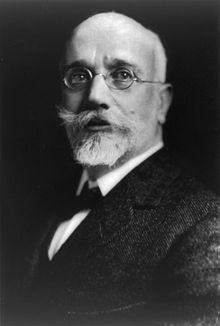

[14][15] Subsequently, an autonomous Republic[note 1] of Northern Epirus was proclaimed on 28 February 1914, in Argyrókastro, following negotiations between representatives of the region's populations and Georgios Christákis-Zográfos, a politician from Lunxhëri and former Greek foreign minister.

In his address on 2 March (the date of the official declaration of independence of Northern Epirus),[17] he elucidated that the national aspirations of the Epirotes had been entirely disregarded and that the major powers had not only rejected the prospect of autonomy within the principality of Albania but also declined to guarantee the region's population their most fundamental rights.

Free from all ties, unable to live united with Albania under these conditions, Northern Epirus proclaims its independence and calls on its citizens to make all necessary sacrifices to defend the integrity of its territory and its freedoms against all attacks, wherever they come from.

[19] In the days following the declaration of independence, Alexandros Karapanos, a nephew of Zográfos and future member of parliament for Arta (in Greece),[20] was appointed to the role of foreign minister of the newly formed republic.

In due course, armed groups such as Spyros Spyromilios' Sacred Band, which was established in the Himara region,[20] were formed to repel any incursions into the territory of the autonomous republic.

[23][24] On 1 March, Kontoulis relinquished control to the recently constituted Albanian gendarmerie, which was composed predominantly of erstwhile Ottoman army deserters under the command of Dutch and Austrian officers.

On 22 March, a Sacred Band from Bilisht reached the outskirts of Korytsá and joined the local guerrillas before engaging in intense street combat within the city.

However, by the time the ceasefire took effect, Northern Epirote forces had already occupied the heights overlooking Korytsá, thereby rendering the surrender of the city's Albanian garrison imminent.

By the terms of this treaty, the provinces of Korytsá and Argyrókastro, which constituted Northern Epirus, were to be granted complete autonomy (as a corpus separatum) under the nominal sovereignty of Prince Wilhelm of Wied.

[30] An assembly of Epirote delegates convened in Dhelvinion also endorsed it, despite objections from Himara's representatives, who advocated enosis (union with Greece) as the sole viable solution for Northern Epirus.

[34] Following the granting of approval by the Great Powers, which underscored the provisional nature of Greece's intervention rights, Athens deployed its military forces into Northern Epirus on 27 October 1914.

[35] In the subsequent days, Italy capitalized on the circumstances to intervene on Albanian soil, occupying Vlora and the island of Sazan, situated in the Otranto Strait region, which is of strategic importance.

[36] In light of the return of the Greek army and the successful conclusion of the enosis (union with Greece), the representatives of the autonomous Northern Epirus Republic proceeded to dissolve the institutional framework they had established.

[39] Following the dismissal of the Prime Minister in October 1915, King Constantine I and his newly appointed government were resolute in their intention to exploit the prevailing international circumstances to formally incorporate the region into Greece.

The Orthodox Metropolitan Vasileios of Dryinoupolis was expelled from his diocese, and ninety Greek leaders from the Himara region (including the mayor) were deported to the island of Favignana or Libya.

Before the convening of the Peace Conference, Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos articulated his country's claims to the Allies in a memorandum dated 30 December 1918.

To rebut the assertion that the Greek population in Albania spoke primarily Albanian, he invoked the precedent of Alsace-Lorraine, citing the German argument that linguistic affiliation should determine regional boundaries.

On 14 January 1920, a session of the Peace Conference, presided over by Georges Clemenceau, ratified the Tittoni-Venizelos agreement, stipulating that its implementation would depend on the resolution of the conflict between Italy and Yugoslavia.

In contrast with the Protocol of Corfu, which designated Northern Epirus as an autonomous region, the government's recognition of the Greek Epirote minority has not resulted in any form of local autonomy.

[67] According to sources from Albania, Italy, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Epirote autonomist movement was a creation of the Greek state, supported by a minority of the region's inhabitants.

[73] In the 1960s, Soviet Union General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev requested that Albanian Head of State Enver Hoxha grant autonomy to the Greek minority in the region.

[76] Two years later, in 1993, the leader of Omonoia publicly elucidated the objective of the Greek minority, which was to achieve the establishment of an autonomous region within the Albanian Republic based on the Protocol of Corfu.