History of Scotland

Following England's Gregorian mission, the Pictish king Nechtan chose to abolish most Celtic practices in favour of the Roman rite, restricting Gaelic influence on his kingdom and avoiding war with Anglian Northumbria.

[22] In the early Iron Age, from the seventh century BC, cellular houses began to be replaced on the northern isles by simple Atlantic roundhouses, substantial circular buildings with a dry stone construction.

[24] There is evidence for about 1,000 Iron Age hill forts in Scotland, most located below the Clyde-Forth line,[25] which have suggested to some archaeologists the emergence of a society of petty rulers and warrior elites recognisable from Roman accounts.

After his victory over the northern tribes at Mons Graupius in 84, a series of forts and towers were established along the Gask Ridge, which marked the boundary between the Lowland and Highland zones, probably forming the first Roman limes or frontier in Scotland.

His reign saw what has been characterised as a "Davidian Revolution", by which Anglo-Norman followers of King David were granted lands and titles and intermixed their institutions with those of Scots intermarrying with the existing aristocracy, underpinning the development of later Medieval Scotland.

He continued a process begun by his mother and brothers helping to establish foundations that brought reform to Scottish monasticism based on those at Cluny and he played a part in organising diocese on lines closer to those in the rest of Western Europe.

[82] Despite the excommunication of Bruce and his followers by Pope Clement V, his support slowly strengthened; and by 1314 with the help of leading nobles such as Sir James Douglas and Thomas Randolph only the castles at Bothwell and Stirling remained under English control.

[88] Despite victories at Dupplin Moor and Halidon Hill, in the face of tough Scottish resistance led by Sir Andrew Murray, the son of Wallace's comrade in arms, successive attempts to secure Balliol on the throne failed.

At this point the majority of the population was probably still Catholic in persuasion and the Kirk found it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.

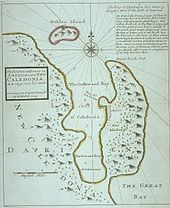

Since the capital resources of the Edinburgh merchants and landholder elite were insufficient, the company appealed to middling social ranks, who responded with patriotic fervour to the call for money; the lower classes volunteered as colonists.

"[140] Historian Jonathan Israel holds that the Union "proved a decisive catalyst politically and economically," by allowing ambitious Scots entry on an equal basis to a rich expanding empire and its increasing trade.

[113]: 2 Historian Jonathan Israel argues that by 1750 Scotland's major cities had created an intellectual infrastructure of mutually supporting institutions, such as universities, reading societies, libraries, periodicals, museums and masonic lodges.

He and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed what he called a 'science of man',[167] which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behave in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity.

Modern sociology largely originated from this movement[168] and Hume's philosophical concepts that directly influenced James Madison (and thus the United States Constitution) and when popularised by Dugald Stewart, would be the basis of classical liberalism.

[176] Merchants who profited from the American trade began investing in leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glassworks, breweries, and soapworks, setting the foundations for the city's emergence as a leading industrial centre after 1815.

[184][185] German sociologist Max Weber mentioned Scottish Presbyterianism in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), and many scholars argued that "this worldly asceticism" of Calvinism was integral to Scotland's rapid economic modernisation.

Originally oriented to clerical and legal training, after the religious and political upheavals of the 17th century they recovered with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry.

From this point until the end of the century, the Whigs and (after 1859) their successors the Liberal Party, managed to gain a majority of the Westminster Parliamentary seats for Scotland, although these were often outnumbered by the much larger number of English and Welsh Conservatives.

[216] The stereotype emerged early on of Scottish colliers as brutish, non-religious and socially isolated serfs;[217] that was an exaggeration, for their life style resembled the miners everywhere, with a strong emphasis on masculinity, equalitarianism, group solidarity, and support for radical labour movements.

[225] The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.

Robert Louis Stevenson's work included the urban Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and played a major part in developing the historical adventure in books like Kidnapped and Treasure Island.

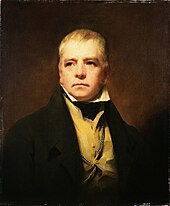

In the 1820s, as part of the Romantic revival, tartan and the kilt were adopted by members of the social elite, not just in Scotland, but across Europe,[233][234] prompted by the popularity of Macpherson's Ossian cycle[235][236] and then Walter Scott's Waverley novels.

This new identity made it possible for Scottish culture to become integrated into a wider European and North American context, not to mention tourist sites, but it also locked in a sense of "otherness" which Scotland began to shed only in the late 20th century.

[242] Land prices subsequently plummeted, too, and accelerated the process of the so-called "Balmoralisation" of Scotland, an era in the second half of the 19th century that saw an increase in tourism and the establishment of large estates dedicated to field sports like deer stalking and grouse shooting, especially in the Scottish Highlands.

The Royal Naval Air Service established flying-boat and seaplane stations on Shetland, at East Fortune and Inchinnan, the latter two also serving as the army's airship bases and protecting Edinburgh and Glasgow, the two largest cities.

The despair reflected what Finlay (1994) describes as a widespread sense of hopelessness that prepared local business and political leaders to accept a new orthodoxy of centralised government economic planning when it arrived during the Second World War.

John MacLean emerged as a key political figure in what became known as Red Clydeside, and in January 1919, the Sheriff of Lanarkshire called for military aid for the understrength Glasgow Police in the middle of a riot during the strike for a Forty Hours working week.

[289] Significant individual contributions to the war effort by Scots included the invention of radar by Robert Watson-Watt, which was invaluable in the Battle of Britain, as was the leadership at RAF Fighter Command of Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding.

[295] Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir and William Soutar, the novelists Neil Gunn, George Blake, Nan Shepherd, A. J. Cronin, Naomi Mitchison, Eric Linklater and Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and the playwright James Bridie.

[285] The introduction in 1989 by the Thatcher-led Conservative government of the Community Charge (widely known as the Poll Tax), one year before the rest of the United Kingdom, contributed to a growing movement for a return to direct Scottish control over domestic affairs.