History of anatomy

The history of anatomy spans from the earliest examinations of sacrificial victims to the advanced studies of the human body conducted by modern scientists.

Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced back thousands of years to ancient Egyptian papyri, where attention to the body was necessitated by their highly elaborate burial practices.

Anatomical knowledge in antiquity would reach its apex in the person of Galen, who made important discoveries through his medical practice and his dissections of monkeys, oxen, and other animals.

The Egyptians seem to have known little about the function of the kidneys and the brain, and made the heart the meeting point of a number of vessels which carried all the fluids of the body—blood, tears, urine, and semen.

[3] In the fifth-century BCE, the philosopher Alcmaeon may have been one of the first to have dissected animals for anatomical purposes, and possibly identified the optic nerves and Eustachian tubes.

The Hippocratic work, On the Heart, for example, contributed a great deal of knowledge to the field of anatomy, even as many of its assumptions regarding physiology were incorrect.

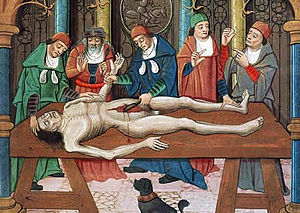

[7] Beginning with Ptolemy I Soter, medical officials were allowed to cut open and examine cadavers for the purposes of learning how human bodies operated.

The first use of human bodies for anatomical research occurred in the work of Herophilos and Erasistratus, who gained permission to perform live dissections, or vivisection, on condemned criminals in Alexandria under the auspices of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Galen was instructed in all major philosophical schools (Platonism, Aristotelianism, Stoicism, and Epicureanism) until his father, moved by a dream of Asclepius, decided he should study medicine.

[10][11] Galen compiled much of the knowledge obtained by his predecessors, and furthered the inquiry into the function of organs by performing dissections and vivisections on Barbary apes, oxen, pigs, and other animals.

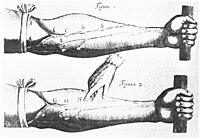

[13][14] It was through his experiments that Galen was able to overturn many long-held beliefs, such as the theory that the arteries contained air, which it carried from the heart and lungs to all parts of the body.

[17] Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī),[a] c. 864 or 865–925 or 935 CE,[b] often known as (al-)Razi or by his Latin name Rhazes, also rendered Rhasis, was a Persian physician, philosopher and alchemist who lived during the Islamic Golden Age.

[27][28][29] As an early anatomist, Ibn al-Nafis also performed several human dissections during the course of his work,[30] making several important discoveries in the fields of physiology and anatomy.

[35] In the 12th century, as universities were being established in Italy, Emperor Frederick II made it mandatory for students of medicine to take courses on human anatomy and surgery.

[42][43] The first major development in anatomy in Christian Europe since the fall of Rome occurred at Bologna, where anatomists dissected cadavers and contributed to the accurate description of organs and the identification of their functions.

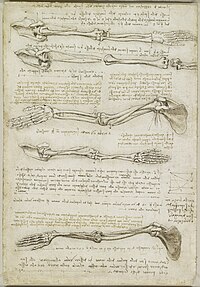

During this time he made use of his anatomical knowledge in his artwork, making many sketches of skeletal structures, muscles, and organs of humans and other vertebrates that he dissected.

[47] For instance, he produced the first accurate depiction of the human spine, while his notes documenting his dissection of the Florentine centenarian contain the earliest known description of cirrhosis of the liver and arteriosclerosis.

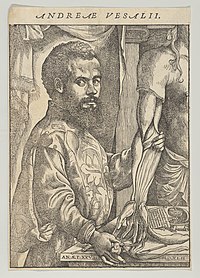

[51] Vesalius was the first to publish a treatise, De Humani Corporis Fabrica, that challenged Galen's anatomical teachings, arguing that they are based on observations of other mammals, not human bodies.

While the lecturer explained human anatomy, as revealed by Galen more than 1000 years earlier, an assistant pointed to the equivalent details on a dissected corpse.

In the late 16th century, anatomists began exploring and pushing for contention that the study of anatomy could contribute to advancing the boundaries of natural philosophy.

[citation needed] The supply of printed anatomy books from Italy and France led to an increased demand for human cadavers for dissections.

Until the middle of the 18th century, there was a quota of ten cadavers for each the Royal College of Physicians and the Company of Barber Surgeons, the only two groups permitted to perform dissections.

By the end of the 18th century, many European countries had passed legislation similar to the Murder Act in England to meet the demand of fresh cadavers and to reduce crime.

The new hospital medicine in France during the late 18th century was brought about in part by the Law of 1794 which made physicians and surgeons equals in the world of medical care.

Ultimately this created the opportunity for the field of medicine to grow in the direction of "localism of pathological anatomy, the development of appropriate diagnostic techniques, and the numerical approach to disease and therapeutics.

"[64] The British Parliament passed the Anatomy Act 1832, which finally provided for an adequate and legitimate supply of corpses by allowing legal dissection of executed murderers.

[75] The history of anatomy in the United States is a rich and multifaceted narrative, closely tied to the evolution of medical education and scientific discovery.

Anatomical education in the U.S. began in the mid-18th century, with notable pioneers like William Shippen Jr., who delivered public lectures on anatomy, including human dissections, in Philadelphia starting in 1762.

Influential educators such as Franklin Paine Mall at the University of Michigan introduced scientific rigor and promoted student-centered learning, setting new standards for teaching anatomy.

It is possible to do this on oneself; in the Integrated Biology course at the University of Berkeley, students are encouraged to "introspect"[76] on themselves and link what they are being taught to their own body.