History of biotechnology

However, both the single-cell protein and gasohol projects failed to progress due to varying issues including public resistance, a changing economic scene, and shifts in political power.

Yet the formation of a new field, genetic engineering, would soon bring biotechnology to the forefront of science in society, and the intimate relationship between the scientific community, the public, and the government would ensue.

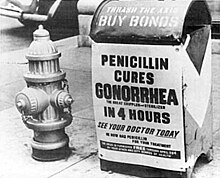

While it seems only natural nowadays to link pharmaceutical drugs as solutions to health and societal problems, this relationship of biotechnology serving social needs began centuries ago.

In late 19th-century Germany, brewing contributed as much to the gross national product as steel, and taxes on alcohol proved to be significant sources of revenue to the government.

The most famous was the private Carlsberg Institute, founded in 1875, which employed Emil Christian Hansen, who pioneered the pure yeast process for the reliable production of consistent beer.

The Hungarian Károly Ereky coined the word "biotechnology" in Hungary during 1919 to describe a technology based on converting raw materials into a more useful product.

In a book entitled Biotechnologie, Ereky further developed a theme that would be reiterated through the 20th century: biotechnology could provide solutions to societal crises, such as food and energy shortages.

[5] This catchword spread quickly after the First World War, as "biotechnology" entered German dictionaries and was taken up abroad by business-hungry private consultancies as far away as the United States.

In Chicago, for example, the coming of prohibition at the end of World War I encouraged biological industries to create opportunities for new fermentation products, in particular a market for nonalcoholic drinks.

Emil Siebel, the son of the founder of the Zymotechnic Institute, broke away from his father's company to establish his own called the "Bureau of Biotechnology," which specifically offered expertise in fermented nonalcoholic drinks.

[1] Initial research work at Lavera was done by Alfred Champagnat,[12] In 1963, construction started on BP's second pilot plant at the Grangemouth Refinery in Scotland.

The Soviets were particularly enthusiastic, opening large "BVK" (belkovo-vitaminny kontsentrat, i.e., "protein-vitamin concentrate") plants next to their oil refineries in Kstovo (1973) [13][14] and Kirishi (1974).

Also, in 1989 in the USSR, the public environmental concerns made the government decide to close down (or convert to different technologies) all 8 paraffin-fed-yeast plants that the Soviet Ministry of Microbiological Industry had by that time.

Before the new direction could be taken, however, the political wind changed again: the Reagan administration came to power in January 1981 and, with the declining oil prices of the 1980s, ended support for the gasohol industry before it was born.

The publisher's blurb for the book warned that within ten years, "You may marry a semi-artificial man or woman…choose your children's sex…tune out pain…change your memories…and live to be 150 if the scientific revolution doesn’t destroy us first.

[1] In response to these public concerns, scientists, industry, and governments increasingly linked the power of recombinant DNA to the immensely practical functions that biotechnology promised.

One of the key scientific figures that attempted to highlight the promising aspects of genetic engineering was Joshua Lederberg, a Stanford professor and Nobel laureate.

With the discovery of recombinant DNA by Cohen and Boyer in 1973, the idea that genetic engineering would have major human and societal consequences was born.

In July 1974, a group of eminent molecular biologists headed by Paul Berg wrote to Science suggesting that the consequences of this work were so potentially destructive that there should be a pause until its implications had been thought through.

Its historic outcome was an unprecedented call for a halt in research until it could be regulated in such a way that the public need not be anxious, and it led to a 16-month moratorium until National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines were established.

At Asilomar, in an atmosphere favoring control and regulation, he circulated a paper countering the pessimism and fears of misuses with the benefits conferred by successful use.

He described "an early chance for a technology of untold importance for diagnostic and therapeutic medicine: the ready production of an unlimited variety of human proteins.

Analogous applications may be foreseen in fermentation process for cheaply manufacturing essential nutrients, and in the improvement of microbes for the production of antibiotics and of special industrial chemicals.

Curing genetic diseases remained in the realms of science fiction, but it appeared that producing human simple proteins could be good business.

[17] The radical shift in the connotation of "genetic engineering" from an emphasis on the inherited characteristics of people to the commercial production of proteins and therapeutic drugs was nurtured by Joshua Lederberg.

Against a belief that new techniques would entail unmentionable and uncontrollable consequences for humanity and the environment, a growing consensus on the economic value of recombinant DNA emerged.

[16] Although market expectations and social benefits of new products were frequently overstated, many people were prepared to see genetic engineering as the next great advance in technological progress.

The main focus of attention after insulin were the potential profit makers in the pharmaceutical industry: human growth hormone and what promised to be a miraculous cure for viral diseases, interferon.

The emergence of interferon and the possibility of curing cancer raised money in the community for research and increased the enthusiasm of an otherwise uncertain and tentative society.

From the perspective of its commercial promoters, scientific breakthroughs, industrial commitment, and official support were finally coming together, and biotechnology became a normal part of business.