History of education in Spain

For the noblest of the people were gathered in Osca, an important city, and brought teachers of Greek and Roman teachings and, in fact, he used them as hostages, but in words he educated them to make them participants, when they were men, of the government and power.

[3]Archaeological remains have been preserved of the so-called "House of Hippolytus" at Complutum (Alcalá de Henares), dating from the 3rd and 4th centuries, a school for young people linked to the Anios family, with recreational and educational uses.

[4][5] Late Antiquity did not entail a total break with the Roman tradition, although in educational institutions the most important effect was its restriction to the Christian religious sphere, particularly the monastic one.

In 1401, Bishop Diego de Anaya founded the first Colegio Mayor, that of San Bartolomé, for poor students, endowing it with sufficient income to provide scholarships.

The real government of the university was exercised by the Master-scholar, who had his own police force and even a prison, since the students enjoyed a privilege that prevented the local authorities from taking action against them.

Their preparation was based on physical education, since the princes had to be agile and leaders of armies, they trained in jumping, javelin, self-defence, use of the sword and lance, horseback riding and hunting; in the study of classical authors and history.

It was a time when university education gave people the opportunity to move up the social ladder and acquire prestige, since their services and knowledge were required by kings.

As for the children, there was no state plan for their education, so they attended the parishes, where the priests (who were not exclusively teachers, because they also carried out other activities) taught them to read, until they were gradually displaced by the Jesuits.

The economic situation of many children forced them to leave school in order to work and support the family economy, although many of them received an education and learned to read in the corporations they joined.

[22] The pedagogical style of Calasanz, who created his first school in Rome in 1597, sought the primary attention to the poorest, the efficiency, the innovation, the graduation of teaching and the synthesis between "Piety and Letters", his motto would be translated today as "Culture and Faith".

[23] Juan Picornell rescues a quote that highlights the importance of the State taking care of education:[24]...if by chance the Republic is increased, it can be said that it grows in men, but not in strength.

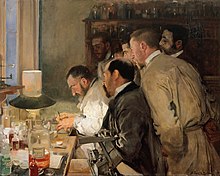

No State, then, will ever be wise, rich or powerful without education.Spanish universities remained on the fringes of philosophical and scientific changes, which resulted in their backwardness in science studies and curricula because they were considered contrary to Catholic doctrine and their traditional, medieval scholastic method.

It retained the power of the Cortes to enact "special plans and statutes", entrusting the Government with the "inspection of public education" through a "general directorate of studies".

[25] The simple curriculum established for primary schools ("to read, write and count, and the catechism of the Catholic religion") is transcendental for the political objective of creating an electoral body of citizens, to which a deadline is set: although for the moment elections were held by universal suffrage (male and indirect), according to Article 25 "From the year one thousand eight hundred and thirty, those who once again enter into the exercise of the rights of citizens must know how to read and write".

The study of modern science, of "the Cartesios and Neutones", was eliminated because, as the professors of the University of Cervera stated, "far from us the dangerous novelty of discourse" ―"it has set us back a century", a student from La Laguna would say―.

Students enrolling for the first time had to present a certificate of "good political and religious conduct" signed by their parish priest and the civil authority, and to receive an academic degree they had to swear an oath to defend the sovereignty of the king, the doctrine of the Council of Constance on regicide and the Immaculate Conception.

Promoted by the Minister of the Interior, Pedro José Pidal, it was drafted mainly by Antonio Gil de Zárate, whose pedagogical principles have been summarised as "freedom, gratuity, centralisation, inspection and uniformity".

Its architect, Claudio Moyano, would resort to the formulation of a basic law which, by setting out the fundamental principles of the system, would thus avoid parliamentary debate on delicate and complex issues.

Understandably, the main feature of this Law was the absolute and direct control of the institutions established in Madrid, with the central government owning and managing them through the Royal Council of Public Instruction.

The structure of the education system was basically as follows; The last years of the reign of Isabella II were characterised by an increase in political repression, especially at the university level.

Several professors (among them Nicolás Salmerón and Miguel Morayta) resigned out of solidarity, and student protests were organised, which were harshly repressed on the so-called Night of St. Daniel (10 April 1865), causing fourteen deaths and one hundred and ninety-three injured.

The Decree of 25 October 1868 reorganised secondary education, reducing the weight of Latin and increasing that of the Castilian language, and introducing subjects such as psychology, art, Spanish history, fundamental principles of law, agriculture and commerce.

An ambitious project of seven subjects per year and a basic revalidation for the awarding of the degree, which failed because it was provocative in the face of complaints from the press, families, politicians and teachers of the time.

In 1933, the Law on Religious Denominations and Congregations (Ley de Confesiones y Congregaciones Religiosas) was passed, which deprived the ecclesiastical establishment of teaching functions.

To avoid the problems caused by their withdrawal, the Substitution Board (Junta de Sustituciones) was created, which meant that when a professor was unable to attend his classes, another teacher would take his place.

In the post-war period, following some debate[36] the Law on Primary Education of 1945 was passed (Ley sobre Educación Primaria de 1945), promoted by the ministry of José Ibáñez Martín.

This law established the rights and duties of teachers and determined their training and the system for admission by competitive examination to the (Cuerpo del Magisterio Nacional Primario).

The Ley Orgánica por la que se regula el Estatuto de Centros Escolares (LOECE) 1980, promoted by the ministry of José Manuel Otero (UCD government).

The different texts, most of which are funerary in nature and come from the urban environment, offer us information about the functions that these professionals carried out in Hispanic society, as well as the socio-legal context from which they came.

In this sense, the most valuable piece is the inscription dedicated to a grammarian named L. Memmius Probus in the ancient Tritium Magallum, thanks to which we know the specific circumstances in which this educator worked.