History of experiments

This article documents the history and development of experimental research from its origins in Galileo's study of gravity into the diversely applied method in use today.

He combined observations, experiments and rational arguments to support his intromission theory of vision, in which rays of light are emitted from objects rather than from the eyes.

[2] Experimental evidence supported most of the propositions in his Book of Optics and grounded his theories of vision, light and colour, as well as his research in catoptrics and dioptrics.

...[5] Alhazen's work included the conjecture that "Light travels through transparent bodies in straight lines only", which he was able to corroborate only after years of effort.

He went so far as to criticize Aristotle for his lack of contribution to the method of induction, which Ibn al-Haytham regarded as being not only superior to syllogism but the basic requirement for true scientific research.

For example, after demonstrating that light is generated by luminous objects and emitted or reflected into the eyes, he states that therefore "the extramission of [visual] rays is superfluous and useless.

[9] Roger Bacon's assertions in the Opus Majus that "theories supplied by reason should be verified by sensory data, aided by instruments, and corroborated by trustworthy witnesses"[10] were (and still are) considered "one of the first important formulations of the scientific method on record".

With this design, Galileo was able to slow down the falling motion and record, with reasonable accuracy, the times at which a steel ball passed certain markings on a beam.

In one experiment, he burned phosphorus and sulfur in air to see whether the results further supported his previous conclusion (Law of Conservation of Mass).

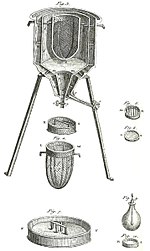

Working with Pierre-Simon Laplace, Lavoisier designed an ice calorimeter apparatus for measuring the amount of heat given off during combustion or respiration.

The center compartment held the source of heat, in this case the guinea pig or piece of burning charcoal.

Lavoisier then measured the mass of the carbonic acid gas and water that were given off during fermentation and weighed the residual liquor, the components of which were then separated and analyzed to determine their elementary composition.

[24] He postulated - and supported with experimental results - the idea that disease-causing agents do not spontaneously appear but are alive and need the right environment to prosper and multiply.

Pasteur's work also led him to advocate (along with the English physician Dr. Joseph Lister) antiseptic surgical techniques.

Most scientists of that day believed that microscopic life sprang into existence from spontaneous generation in non-living matter.

Dust (which Pasteur thought contained microorganisms) would be trapped at the bottom of the first curve, but the air would flow freely through.

[26] Despite the experimental results supporting his hypotheses and his success curing or preventing various diseases, correcting the public misconception of spontaneous generation proved a slow, difficult process.

As he worked to solve specific problems, Pasteur sometimes revised his ideas in the light of the results of his experiments, as when faced with the task of finding the cause of disease devastating the French silkworm industry in 1865.

After a year of diligent work he correctly identified a culprit organism and gave practical advice for developing a healthy population of moths.

[27] "In reforming optics he, as it were, adopted ‘‘positivism’’ (before the term was invented): we do not go beyond experience, and we cannot be content to use pure concepts in investigating natural phenomena.

Thus, once he has assumed light is a material substance, Ibn al-Haytham does not discuss its nature further, but confines himself to considering its propagation and diffusion.

In his optics ‘‘the smallest parts of light’’, as he calls them, retain only properties that can be treated by geometry and verified by experiment; they lack all sensible qualities except energy."