History of nuclear weapons

[1] In August 1945, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were conducted by the United States, with British consent, against Japan at the close of that war, standing to date as the only use of nuclear weapons in hostilities.

[3] In a 1924 article, Winston Churchill speculated about the possible military implications: "Might not a bomb no bigger than an orange be found to possess a secret power to destroy a whole block of buildings—nay to concentrate the force of a thousand tons of cordite and blast a township at a stroke?

After Fermi achieved the world's first sustained and controlled nuclear chain reaction with the creation of the first atomic pile, massive reactors were secretly constructed at what is now known as the Hanford Site to transform uranium-238 into plutonium for a bomb.

In April 1944 it was found by Emilio Segrè that the plutonium-239 produced by the Hanford reactors had too high a level of background neutron radiation, and underwent spontaneous fission to a very small extent, due to the unexpected presence of plutonium-240 impurities.

If such plutonium were used in a gun-type design, the chain reaction would start in the split second before the critical mass was fully assembled, blowing the weapon apart with a much lower yield than expected, in what is known as a fizzle.

The difficulties with implosion centered on the problem of making the chemical explosives deliver a perfectly uniform shock wave upon the plutonium sphere— if it were even slightly asymmetric, the weapon would fizzle.

[21] After D-Day, General Groves ordered a team of scientists to follow eastward-moving victorious Allied troops into Europe to assess the status of the German nuclear program (and to prevent the westward-moving Soviets from gaining any materials or scientific manpower).

The Japanese navy lost interest when a committee led by Yoshio Nishina concluded in 1943 that "it would probably be difficult even for the United States to realize the application of atomic power during the war".

Under the clause of the 1943 Quebec Agreement that specified that nuclear weapons would not be used against another country without mutual consent, the atomic bombing of Japan was recorded as a decision of the Anglo-American Combined Policy Committee.

Truman and his Secretary of State James F. Byrnes were also intent on ending the Pacific war before the Soviets could enter it,[28] given that Roosevelt had promised Stalin control of Manchuria if he joined the invasion.

The Soviet program, under the suspicious watch of former NKVD chief Lavrenty Beria (a participant and victor in Stalin's Great Purge of the 1930s), would use the Report as a blueprint, seeking to duplicate as much as possible the American effort.

[48] Indeed, within the U.S. government, including the Departments of State and Defense, there was considerable confusion over who actually knew the size of the stockpile, and some people chose not to know for fear they might disclose the number accidentally.

[47] The notion of using a fission weapon to ignite a process of nuclear fusion can be dated back to September 1941, when it was first proposed by Enrico Fermi to his colleague Edward Teller during a discussion at Columbia University.

The Joe-1 atomic bomb test by the Soviet Union that took place in August 1949 came earlier than expected by Americans, and over the next several months there was an intense debate within the U.S. government, military, and scientific communities regarding whether to proceed with development of the far more powerful Super.

The reasons were in part because the success of the technology seemed limited at the time (and not worth the investment of resources to confirm whether this was so), and because Oppenheimer believed that the atomic forces of the United States would be more effective if they consisted of many large fission weapons (of which multiple bombs could be dropped on the same targets) rather than the large and unwieldy super bombs, for which there was a relatively limited number of targets of sufficient size to warrant such a development.

On March 1, 1954, the U.S. detonated its first practical thermonuclear weapon (which used isotopes of lithium as its fusion fuel), known as the "Shrimp" device of the Castle Bravo test, at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands.

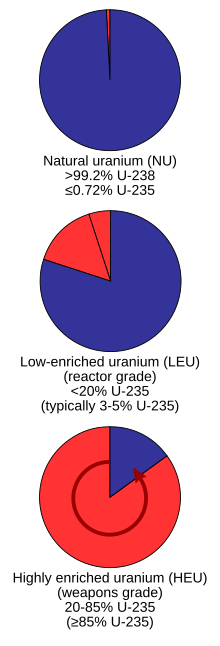

While technically true, this hid a more gruesome point: the last stage of a multi-staged hydrogen bomb often used the neutrons produced by the fusion reactions to induce fissioning in a jacket of natural uranium and provided around half of the yield of the device itself.

Early nuclear armed rockets—such as the MGR-1 Honest John, first deployed by the U.S. in 1953—were surface-to-surface missiles with relatively short ranges (around 15 mi/25 km maximum) and yields around twice the size of the first fission weapons.

This apparent paradox of nuclear war was summed up by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill as "the worse things get, the better they are"—the greater the threat of mutual destruction, the safer the world would be.

Also involved in the debate about nuclear weapons policy was the scientific community, through professional associations such as the Federation of Atomic Scientists and the Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs.

The "Baby Tooth Survey," headed by Dr Louise Reiss, demonstrated conclusively in 1961 that above-ground nuclear testing posed significant public health risks in the form of radioactive fallout spread primarily via milk from cows that had ingested contaminated grass.

The international politics of brinkmanship led leaders to exclaim their willingness to participate in a nuclear war rather than concede any advantage to their opponents, feeding public fears that their generation may be the last.

Civil defense programs undertaken by both superpowers, exemplified by the construction of fallout shelters and urging civilians about the survivability of nuclear war, did little to ease public concerns.

The missiles had 2,400 mile (4,000 km) range and would allow the Soviet Union to quickly destroy many major American cities on the Eastern Seaboard if a nuclear war began.

Fears of communication difficulties led to the installment of the first hotline, a direct link between the superpowers that allowed them to more easily discuss future military activities and political maneuverings.

An improved version of 'Fat Man' was developed, and on 26 February 1952, Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced that the United Kingdom had an atomic bomb and a successful test took place on 3 October 1952.

This doctrine resulted in a large increase in the number of nuclear weapons, as each side sought to ensure it possessed the firepower to destroy the opposition in all possible scenarios.

These systems were used to launch satellites, such as Sputnik, and to propel the Space Race, but they were primarily developed to create Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) that could deliver nuclear weapons anywhere on the globe.

In a major move of symbolic de-escalation, Boris Yeltsin, on January 26, 1992, announced that Russia planned to stop targeting United States cities with nuclear weapons.

"[88] Known as the Vela incident, it was speculated to have been a South African or possibly Israeli nuclear weapons test, though some feel that it may have been caused by natural events or a detector malfunction.