History of science and technology in Spain

Whilst scientific and technical activities are as old as the human race, instances of integrating systematic knowledge, material resources, skills and technical procedures to transform a production process through the application of a defined methodology surfaced at the start the late modern period; in the case of Spain, this came tragically late, in contrast to the verve with which she had become one of the first to enter the early modern period.

Science and technology in Spain, in the 19th century until the beginning of the 20th century, was such a "marginal feature of its administrative and social structures",[2] that this very marginality came to be used as a sort of Spanish national stereotype, spread and celebrated by some foreign media, rejected as being pejorative or belittling but on occasion seized on with haughty pride, as in Miguel de Unamuno's immortal phrase, repeatedly used and abused ever since, on both sides of the argument, to the extent of becoming a literary motif or cliché: ¡Que inventen ellos!

The pre-neanderthal (Homo Heidelbergensis) finds at the Atapuerca site near Burgos in Spain offer one of the most promising directions for paleoanthropological research: to establish the degree of oral communication in that species by reconstruction of the sound-producing mechanism (hyoid) and hearing apparatus (bone structure and inner-ear cavity).

[8] During the first civilisations in the Middle East, the part played by the "Far Western" regions in long-distance metal trading was vital for the development there of Bronze Age metallurgical techniques.

Next, around 1000BC, Iron Age metallurgy was introduced simultaneously but independently to Iberia by Mediterranean colonisers (Greek and Phoenician) on the southern and eastern coasts, and by Celts from Central Europe in the centre, west and north.

Some of the most important scientists of the Hellenistic period came to Cádiz, such as Polybius, Artemidorus and Posidonius, who took the chance while there to make measurements of the tides (more visible in the Atlantic than in the Mediterranean) and suggest their causes.

The following quotation from Columela shows clearly how the speculative nature of Greco-Roman scientific activity was disconnected from technology and manual work, reflecting the basic separation between the "otium" (leisure time) fitting for philosophers, and the world of "negotium" (commerce) and slavery.

And I can never cease to wonder, when I consider how those who wish to speak well choose an orator whose eloquence they imitate; those who wish to learn the rules of calculation and measurement seek a master of this learning who pleases them so much; those who love music and dance take great care to find masters of these arts; those who want to construct a building call upon tradesmen and architects; those who wish to sail the sea seek men who know how to manage a boat; those who engage in war seek skilled tacticians; in short, everyone taking pains to find the best guide they can for that field of study to which they want to apply themselves...: only agriculture, which is certainly very close to wisdom, and has some sort of kinship with her, lacks pupils to learn it and masters to teach it.It was in the Iberian peninsula that medieval science saw some of its greatest developments.

The transition from feudalism to capitalism implied technological changes driven forward or hindered by the different socio-economic structures, which in Spain were made manifest in the different forms of innovation in agriculture, livestock farming, food production and other crafts.

The incorporation of the later medieval kingdoms of Spain into European trade routes between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean stimulated not only seafaring technology and the associated map-making and astronomical studies, but also the introduction of new commercial and financial institutions.

This lay at the root of some of the issues that determined the course of cultural and intellectual history, such as the dialectic between New and Old Christians, and the shaping of the financial and tax-collecting systems of the nascent authoritarian monarchy after its unification by the Catholic Monarchs.

The economic importance of the Spanish treasure fleet and the exploitation of minerals from the New World called for science and technology of the highest level, above all in the maritime and metallurgical fields.

On that occasion the Spanish master Ruy López de Segura, up to then considered the best practical and theoretical exponent of chess, was dethroned by the Italian Leonardo da Cutri.

And how certain it is that trying to diverge from the decree of an outdated opinion is among the hardest things that men attempt!Throughout the Age of Enlightenment, the awareness of the poor state of science and technology in Spain arose out of the "negative introspection" of the arbitristas of the 17th and especially the 18th century.

It is in this context that we should view the famous speech of Don Quixote on "weapons and letters":[19] while in the Middle Ages the knight may have distinguished himself mainly by his military adventures, from the Renaissance onward it became clear that high rank did not have to conflict with intellectual development.

Of greater importance even than the systematic destruction of infrastructure by both French and British armies, such as the textile industry of Béjar[27] or the porcelain manufacture of Buen Retiro in Madrid, was the "brain drain" resulting from the exiling in turn of Francophiles and Liberals.

[28][29] At any rate, the gathering together of funds scattered during the sackings allowed the opening of the Prado Museum in Madrid, in the building originally intended as the base for the Royal Office for Science, the National Library, and other academic institutions.

The liberal programmes, especially those of the progresistas (in power 1854–1856 and 1868–1874), but also to a lesser extent of the moderados, included the promotion of railway-building and mining, opening Spain to foreign investment from France, Belgium and Britain.

At present, when scientific research has become a recognised profession with State funding ... those former times have passed when anyone curious about Nature, shut in the silence of his study, could be sure that no rival would disturb his quiet musings.

In Spain, where laziness is not just a vice but a religion, people find it hard to grasp those monumental works of the German chemists, physicists and doctors, in which it would appear that just making the diagrams and searching the literature must take decades, and yet those books have been written within one or two years.

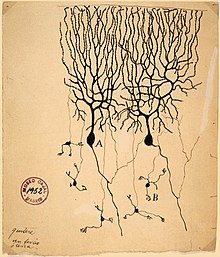

The whole secret lies in the method of study ... in short, in not incurring the mental expense of that witty chat of the café and the social gathering, which takes away our nervous energy and with new and futile concerns distracts us from the main task.The Spanish Civil War was another tragedy for Spanish science, bringing about the exile of a whole generation of scientists – the next Spaniard to win the Nobel Prize for medicine, Severo Ochoa in 1959,[33] had taken American citizenship – and the moribund intellectual life in "internal exile" of many other scientists during the long poverty-stricken postwar period depicted in Luis Martín-Santos' novel Time of Silence (Tiempo de silencio).

The policy of autarky, and the concentration of capital in large banking and industrial corporations, gave some opportunity for scientific and technological development in strategic sectors such as shipbuilding, petrochemicals and hydroelectricity.

... Our present-day science, in common with that which defined us in past centuries as a nation and an empire, seeks to be above all CatholicIndividual or collective achievements such as the Talgo train or the eradication of malaria[35] were held up as glories of Francoist Spain, regardless of their importance – e.g., the heart transplant attempted by the Marquis of Villaverde, son-in-law to Franco himself, in September 1968, when the patient died the next day.