History of scientific method

Aristotle pioneered scientific method in ancient Greece alongside his empirical biology and his work on logic, rejecting a purely deductive framework in favour of generalisations made from observations of nature.

Some of the most important debates in the history of scientific method center on: rationalism, especially as advocated by René Descartes; inductivism, which rose to particular prominence with Isaac Newton and his followers; and hypothetico-deductivism, which came to the fore in the early 19th century.

For example, in his treatise on mineralogy, Kitab al-Jawahir (Book of Precious Stones), al-Biruni is "the most exact of experimental scientists", while in the introduction to his study of India, he declares that "to execute our project, it has not been possible to follow the geometric method" and thus became one of the pioneers of comparative sociology in insisting on field experience and information.

He argued that if instruments produce errors because of their imperfections or idiosyncratic qualities, then multiple observations must be taken, analyzed qualitatively, and on this basis, arrive at a "common-sense single value for the constant sought", whether an arithmetic mean or a "reliable estimate.

[38] In the On Demonstration section of The Book of Healing (1027), the Persian philosopher and scientist Avicenna (Ibn Sina) discussed philosophy of science and described an early scientific method of inquiry.

[45] During the European Renaissance of the 12th century, ideas on scientific methodology, including Aristotle's empiricism and the experimental approaches of Alhazen and Avicenna, were introduced to medieval Europe via Latin translations of Arabic and Greek texts and commentaries.

[55] Limbrick 1988 notes that 630 editions, translations, and commentaries on Galen were produced in Europe in the 16th century, eventually eclipsing Arabic medicine there, and peaking in 1560, at the time of the scientific revolution.

[57] To counter this, a botanical garden was established at Orto botanico di Padova, University of Padua (in use for teaching by 1546), in order that medical students might have empirical access to the plants of a pharmacopia.

[58] The first printed work devoted to the concept of method is Jodocus Willichius, De methodo omnium artium et disciplinarum informanda opusculum (1550).

An Informative Essay on the Method of All Arts and Disciplines (1550) [59] In 1562 Outlines of Pyrrhonism by the ancient Pyrrhonist philosopher Sextus Empiricus (c. 160–210 AD) was published in a Latin translation (from Greek), quickly placing the arguments of classical skepticism in the European mainstream.

In this, he is echoed by Francis Bacon who was influenced by another prominent exponent of skepticism, Montaigne; Sanches cites the humanist Juan Luis Vives who sought a better educational system, as well as a statement of human rights as a pathway for improvement of the lot of the poor.

"Sanches develops his scepticism by means of an intellectual critique of Aristotelianism, rather than by an appeal to the history of human stupidity and the variety and contrariety of previous theories."

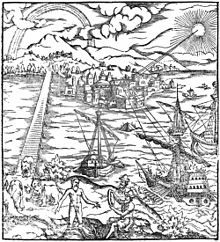

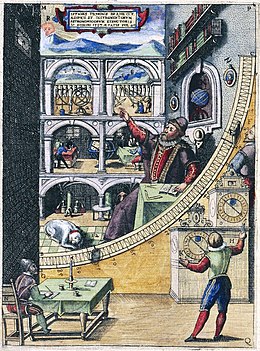

Astonished by the existence of a star that ought not to have been there and gaining the patronage of King Frederick II of Denmark, Tycho built the Uraniborg observatory at enormous cost.

Over a period of fifteen years (1576–91), Tycho and upwards of thirty assistants charted the positions of stars, planets, and other celestial bodies at Uraniborg with unprecedented accuracy.

As Bacon put it, [A]nother form of induction must be devised than has hitherto been employed, and it must be used for proving and discovering not first principles (as they are called) only, but also the lesser axioms, and the middle, and indeed all.

In Bacon's utopian novel, The New Atlantis, the ultimate role is given for inductive reasoning: Lastly, we have three that raise the former discoveries by experiments into greater observations, axioms, and aphorisms.

In 1619, René Descartes began writing his first major treatise on proper scientific and philosophical thinking, the unfinished Rules for the Direction of the Mind.

In this sense, he was a Platonist, as he believed in the innate ideas, as opposed to Aristotle's blank slate (tabula rasa), and stated that the seeds of science are inside us.

Implicitly rejecting Descartes' emphasis on rationalism in favor of Bacon's empirical approach, he outlines his four "rules of reasoning" in the Principia, But Newton also left an admonition about a theory of everything: To explain all nature is too difficult a task for any one man or even for any one age.

Attempts to systematize a scientific method were confronted in the mid-18th century by the problem of induction, a positivist logic formulation which, in short, asserts that nothing can be known with certainty except what is actually observed.

[94] Whewell's sophisticated concept of science had similarities to that shown by Herschel, and he considered that a good hypothesis should connect fields that had previously been thought unrelated, a process he called consilience.

Mill may be regarded as the final exponent of the empirical school of philosophy begun by John Locke, whose fundamental characteristic is the duty incumbent upon all thinkers to investigate for themselves rather than to accept the authority of others.

Firstly, speaking in broader context in "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (1878),[98] Peirce outlined an objectively verifiable method to test the truth of putative knowledge on a way that goes beyond mere foundational alternatives, focusing upon both Deduction and Induction.

Peirce examined and articulated the three fundamental modes of reasoning that play a role in scientific inquiry today, the processes that are currently known as abductive, deductive, and inductive inference.

Many of Peirce's ideas were later popularized and developed by Ronald A. Fisher, Jerzy Neyman, Frank P. Ramsey, Bruno de Finetti, and Karl Popper.

[citation needed] Ludwik Fleck, a Polish epidemiologist who was contemporary with Karl Popper but who influenced Kuhn and others with his Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact (in German 1935, English 1979).

[100] Critics of Popper, chiefly Thomas Kuhn, Paul Feyerabend and Imre Lakatos, rejected the idea that there exists a single method that applies to all science and could account for its progress.

In the judicial system and in public policy controversies, for example, a study's deviation from accepted scientific practice is grounds for rejecting it as junk science or pseudoscience.

An advertisement in which an actor wears a white coat and product ingredients are given Greek or Latin sounding names is intended to give the impression of scientific endorsement.

Richard Feynman has likened pseudoscience to cargo cults in which many of the external forms are followed, but the underlying basis is missing: that is, fringe or alternative theories often present themselves with a pseudoscientific appearance to gain acceptance.