History of speciation

The 20th century saw the growth of the field of speciation, with major contributors such as Ernst Mayr researching and documenting species' geographic patterns and relationships.

[4]: 125 Controversy exists as to whether Charles Darwin recognized a true geographical-based model of speciation in his publication On the Origin of Species.

[5] The evolutionary biologist James Mallet maintains that the mantra repeated concerning Darwin's Origin of Species book having never actually discussed speciation is specious.

[1][8] Similar claims were promulgated by the mutationist school of thought during the late 20th century, and even after the modern evolutionary synthesis by Richard Goldschmidt.

[9] However, Mayr's view has not been entirely accepted, as Darwin's transmutation notebooks contained writings concerning the role of isolation in the splitting of species.

Darwin pointed out that by the theory of natural selection "innumerable transitional forms must have existed," and wondered "why do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth."

[11] A possible explanation for how these dilemmas can be resolved is discussed in the article Speciation in the section "Effect of sexual reproduction on species formation."

[4]: 2 Karl Jordan is thought to have recognized the unification of mutation and isolation in the origin of new species — in stark contrast to the prevailing views at the time.

[14]: 486 David Starr Jordan reiterated Wagner's proposal in 1905, providing a wealth of evidence from nature to support the theory,[16][20][4]: 2 and asserting that geographic isolation is obvious but had been unfortunately ignored by most geneticists and experimental evolutionary biologists at the time.

[21] Mayr's 1942 publication, influenced heavily by the ideas of Karl Jordan and Poulton, was regarded as the authoritative review of speciation for over 20 years—and is still valuable today.

This concept arose by an interpretation of Wagner's Separationstheorie as a form of founder effect speciation that focused on small geographically isolated species.

[26][27][28] Many geneticists at the time did little to bridge the gap between the genetics of natural selection and the origin of reproductive barriers between species.

[4]: 2 He recognized that speciation was an unsolved problem in biology at the time, rejecting Darwin's position that new species arose by occupation of new niches — contending that reproductive isolation was instead based on barriers to gene flow.

[4]: 2 Subsequently, Mayr conducted extensive work on the geography of species, emphasizing the importance of geographic separation and isolation, in which he filled Dobzhansky's gaps concerning the origin of biodiversity (in his 1942 book).

[4]: 4 The study of speciation has seen its largest increase since the 1980s[4]: 4 with an influx of publications and a host of new terms, methods, concepts, and theories.

[21] This "third phase" of work — as Jerry A. Coyne and H. Allen Orr put it — has led to a growing complexity of the language used to describe the many processes of speciation.

[21] Coyne and Orr discuss the modern, post-1980s developments centered around five major themes: Ecologists became aware that the ecological factors behind speciation were under-represented.

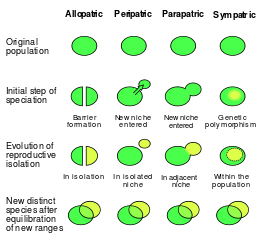

He originally proposed the three primary modes known today: geographic, semi-geographic, non-geographic;[21] corresponding to allopatric, parapatric, and sympatric respectively.

[45] Coyne and Orr argue that the geographic classification scheme is valuable in that biogeography controls the strength of the evolutionary forces at play, as gene flow and geography are clearly linked.

[44] James Mallet and colleagues contend that the sympatric vs. allopatric dichotomy is valuable to determine the degree in which natural selection acts on speciation.

[47] Kirkpatrick and Ravigné categorize speciation in terms of its genetic basis or by the forces driving reproductive isolation.

[48] Fitzpatrick and colleagues believe that the biogeographic scheme "is a distraction that could be positively misleading if the real goal is to understand the influence of natural selection on divergence.

"[44] They maintain that, to fully understand speciation, "the spatial, ecological, and genetic factors" involved in divergence must be explored.

[52] Historically, zoologists considered hybridization to be a rare phenomenon, while botanists found it to be commonplace in plant species.

[54] Wallace's hypothesis differed from the modern conception in that it focused on post-zygotic isolation, strengthened by group selection.

[4]: 353 [55][56] Dobzhansky was the first to provide a thorough, modern description of the process in 1937,[4]: 353 though the actual term itself was not coined until 1955 by W. Frank Blair.

[4]: 353 In the 1980s, many evolutionary biologists began to doubt the plausibility of the idea,[4]: 353 based not on empirical evidence, but largely on the growth of theory that deemed it an unlikely mechanism of reproductive isolation.

Since the early 1990s, reinforcement has seen a revival in popularity, with perceptions by evolutionary biologists accepting its plausibility—due primarily from a sudden increase in data, empirical evidence from laboratory studies and nature, complex computer simulations, and theoretical work.

[63] Maria R. Servedio and Mohamed Noor consider any detected increase in pre-zygotic isolation as reinforcement, as long as it is a response to selection against mating between two different species.

[64] Coyne and Orr contend that, "true reinforcement is restricted to cases in which isolation is enhanced between taxa that can still exchange genes".